Is it time to ban the B-word, mean girls?

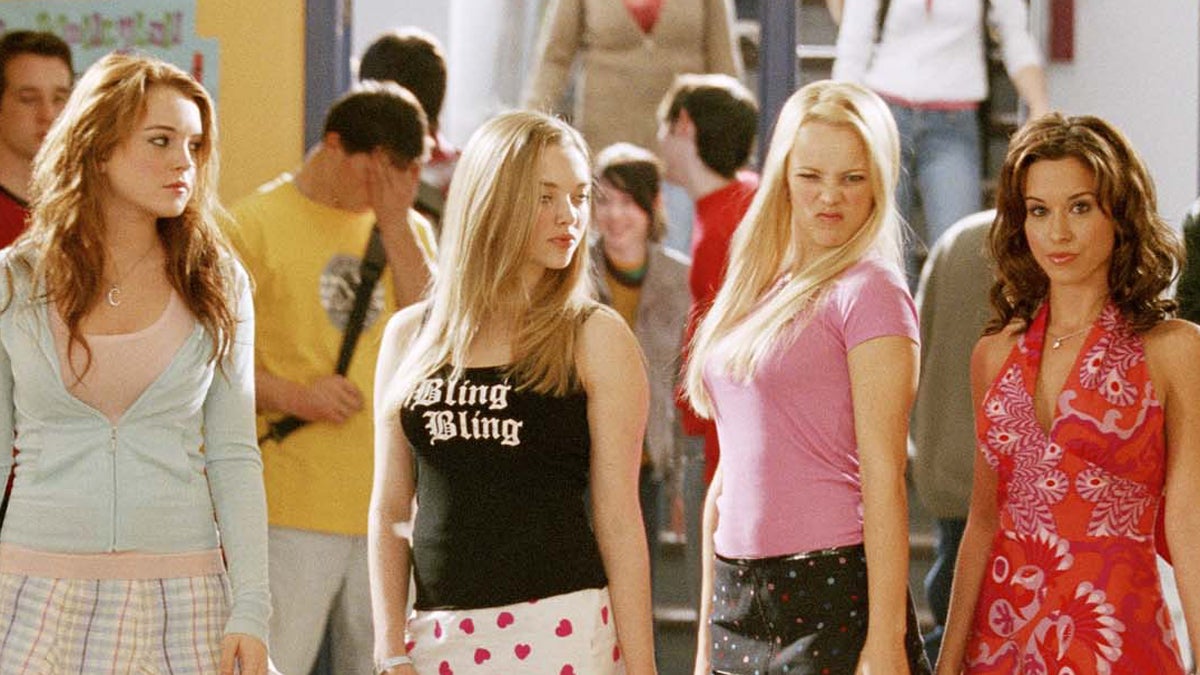

Lindsay Lohan as Cady, Amanda Seyfried as Karen, Rachel McAdams as Regina and Lacey Chabert as Gretchen in the 2004 film 'Mean Girls.' (AP Photo/ Michael Gibson)

I want to ban the B-word.

You know the one I mean; it rhymes with “itch,” and you can find it everywhere these days, a casual pox: Lyrics by Jay-Z and Kanye West. A cotton sweater emblazoned “Supreme Bitch” from the company LotOTees. The title of a short-lived sitcom, “Don’t Trust the B— in Apt. 23.”

Or in conversation at a recent writers’ conference. Just before the opening program, a woman shows me photos of her raven-haired daughter, who is studying art education at SUNY New Paltz. Then she tells me her daughter’s been having a hard time with her roommates, three young women who share a house near campus.

“Face it, women are bitches,” she says.

I’m a little shocked. A gathering of folks who cherish nuanced language and original expression … and that’s the only word she can think of? Worse, her statement is categorical, broad-brushing not just her daughter’s difficult housemates but women in general, present company presumably included.

Really? All of us?

My mind performs a brisk shuffle: my partner of 24 years; my Bubbies with their knitting and blintzes; the dentist who cracks me up while the plastic straw is slurping saliva from my mouth; the best friend who hears the catch in my voice and counsels, “You need to cry.”

I think about what this near-stranger has told me — an incontrovertible truth, as if she’d declared that winter was cold or tape was sticky or George Bush was a Republican. I think she expected laughing acquiescence: “Yeah, I know, aren’t we?” But I couldn’t sign on to the joke.

Girls only

It’s partly that “bitch,” like “slut” and “whore,” has no male counterpart. These words are front-loaded with centuries of misogynist baggage, a double standard that punishes women for assertiveness and frank sexuality while lauding the same qualities in men.

A man who shows decisiveness, voices public disagreement or challenges the status quo is “authoritative,” “charismatic” or “bold.” A woman who does those things gets tagged as … well, you know.

Lest you think I’m drawing on some dreary memories from the bad ol’ days of sexism, listen to the conclusions of a recent survey on how people respond to mouthy women in the workplace.

A Yale psychologist asked professional men and women to assess the competence of chief executives. Male CEOs who spoke more than their peers were rewarded with 10 percent higher ratings of competence, but when female executives spoke more than their peers, both genders punished them with 14 percent lower ratings.

Now imagine my writing conference scenario with the genders reversed. A middle-aged man tells another graying bloke that his son has been struggling with the guys on the soccer team. “Face it, men are assholes,” he says.

“Yeah,” his companion grunts back.

It’s a different story: A man declaring “men are assholes” is chummy self-deprecation, an insult men can afford because, no matter how badly they behave, they’re still going to earn a dollar for every woman’s 78 cents. They’re still going to hold 95 percent of Fortune 500 CEO positions and write 62 percent of the books reviewed in the New York Times Book Review. You may be an irredeemable jerk, or a guy just having a bad day, but you’re still a back-slapping member of the Superiority Club.

But when a woman says, “Women are bitches” — or the tween counterpart, “Girls are just mean!” — it’s not a gesture of solidarity or an ironic nod to our gender’s elevated status. It’s not a joke.

When a woman calls another woman a bitch, she’s feeling neither superior nor sisterly. More likely, she’s feeling stung. I’d bet that at some point in her life (remember 7th grade?) she found herself on the wrong side of a wounding encounter with one of her own sex, and this is the meaning she’s made of it.

Why the ‘mean girl’?

But surely that can’t be the end of the story. We’d never accept a bumper-sticker summation of some other group: “Yeah, Jews are just money-grubbers” or “Those lesbians, they sure are ugly.” I can barely write such lies, and I don’t know anyone, male or female, who would utter them; so why does that B-word roll readily off even female tongues?

What would happen if we peeked beneath the label? What’s really going on, I wonder, when a woman undermines her female colleague or spreads rumors about a sorority sister? What makes a middle-school girl add a snarky tag to an Instagram photo posted by last week’s BFF?

What disturbs me most is the way the B-word feels like a shrug of resignation. It closes the door to curiosity, and to change. If it’s simply a sad fact that girls are mean and women are bitchy, then what hope is there for intervention, for transformation, for figuring out what the hell is going on in the girls’ room and then making it better?

Maybe the female exec’s in a vile mood because, every time she opens her mouth at a meeting, the men at the table interrupt or frown or act like a mosquito just buzzed. Maybe the college sophomore spreading nasties about her sorority pal feels lousy about her own body. And the middle-school girl who turns on her former BFF? Probably beset by envy, insecurity, a torrent of pubescent feeling that no one’s helping her express.

I’ve seen women try to reclaim the B-word, the way LGBT folks took “queer” back from the homophobes, but I just can’t bend my brain around it. Maybe because “bitch” is a word that’s still used, by both genders, in all earnestness, to beat us up.

I’m not advocating some dewy-eyed vision of female unity. I’m not saying that 7th-grade girls ought to start the day by joining hands and singing Holly Near ballads. I’ve met my share of imperious female teachers, entitled and bossy teen girls and — in one indelible instance in my early 30s — a pal who said she didn’t want to be my friend anymore, ever, then stopped returning my calls.

“Bitch,” I could have said. But I didn’t. It’s too facile, too dismissive. I’ll probably never know the story behind my friend’s rejection — a tale, I’m guessing, tangled with misunderstanding, resentment or regret — but I do know that one word, especially that word, could never capture her, or me, or any woman, complicated creatures all.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.