Into the woods: Fairmount Park groups aim to orient Belmont trail runners

This post was created in collaboration with Hidden City. Photos by Bradley Maule. Check out previous collaborations here.

When I decided to make Philadelphia my permanent home, in 2005, I moved into a friend’s apartment at the corner of 30th and Ogden streets, in a neighborhood that I referred to at the time as Behind the Art Museum. My third-floor bedroom overlooked a freight rail line, across Sedgley Drive, onto Lemon Hill.

For two years I lived that close to Fairmount Park, the greenest place in the city, but aside from a few short walks around Lemon Hill and one half-memorable night drinking a few beers on a stone barrier above Kelly Drive, I didn’t really explore it. Now that I live in the treeless tundra of South Philly, I wonder what the hell was wrong with me.

A few weeks ago, I went on a walk in the woods around the Belmont Plateau with Bradley Maule, the photographer and trash collector, and Chris Dougherty, project manager at Fairmount Park Conservancy. I wanted Dougherty to show me a series of cross-country racing trails, the Belmont Trails, which the Conservancy and Philadelphia Parks and Recreation are in the beginning stages of outfitting with signs that tell trail visitors where they are, and where they’re going.

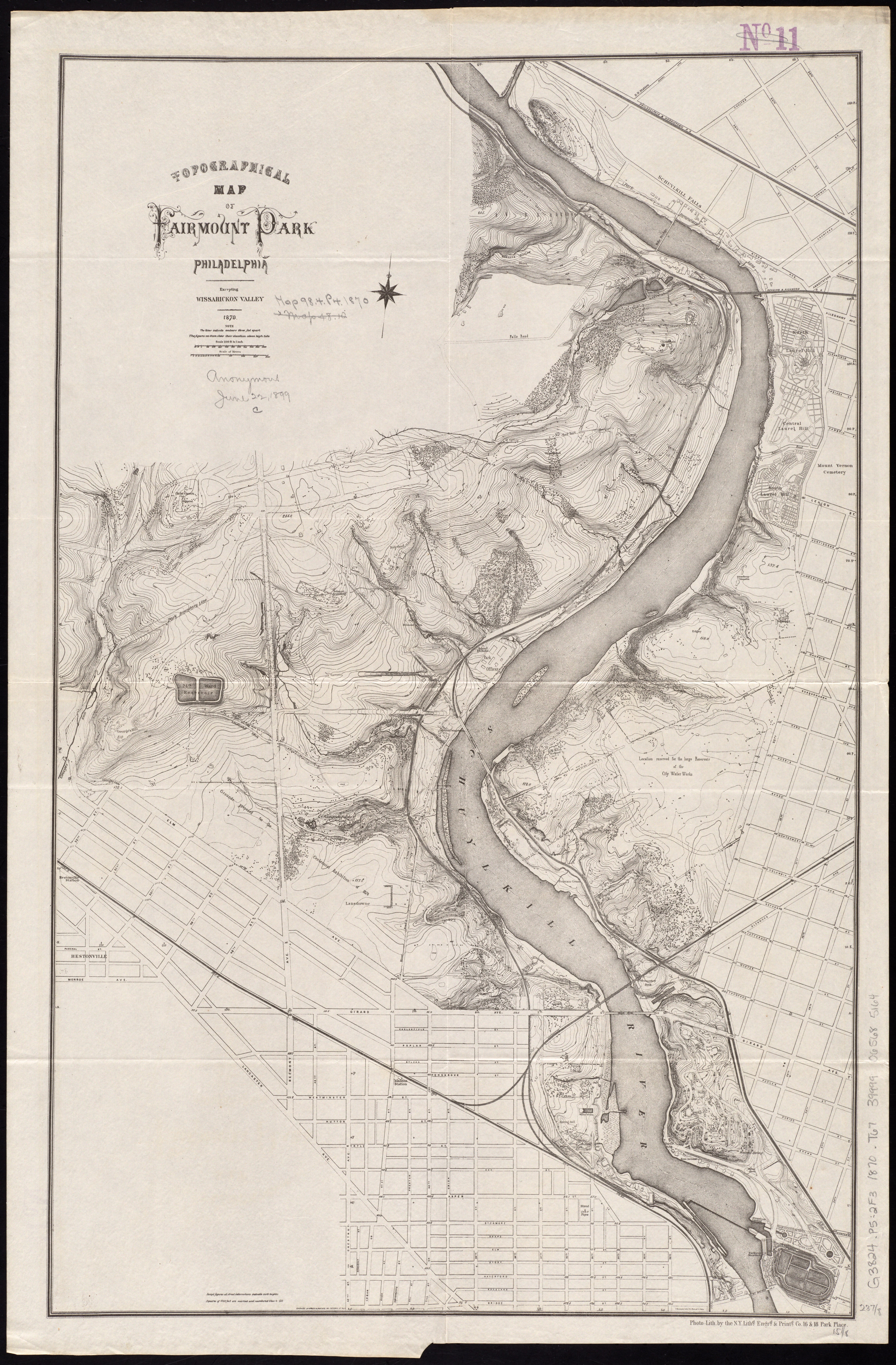

The signs follow the cues given by Friends of the Wissahickon’s signage and wayfinding project currently underway in that section of Fairmount Park. The Belmont improvements are expected to cost around $150,000, funded almost entirely with money from one year’s Broad Street Run. The Conservancy has been a recipient of some of the proceeds from the annual race since 2013.

The trails start at the bottom of the hill at the Plateau. Three of them—3, 5, and 8 kilometers, used primarily by cross country racers and mountain bikers—snake into the woods of West Fairmount Park. They follow, at times, the paths of trolley routes that were decommissioned after World War II. They cross over narrow tributary streams to the Schuylkill River, fallen trees, and wind up and down small hills.

Within a few minutes’ walk, I was disoriented. Not lost, like I couldn’t have found my way out—the park’s not that big—but without a sense of where I was heading.

“We’ve identified over the years the need for improvements, particularly signage, to facilitate increased and higher use of the trails,” said Mark Focht, a deputy commissioner at the Department of Parks & Recreation.

Dave Thomas, the head cross country coach at Philadelphia University, has been running on the Belmont Trails since the 1970s. For the past eight years, he’s also been out on the trails chopping down weeds, and placing mile markers and directional signs of his own accord.

“Being a race organizer myself … I just sensed that no one was doing the job, and I kind of wanted to step up a little bit,” Thomas said.

Thomas is also the founder of a nonprofit group called Philadelphia Athletic Charities, which has supported races on the Belmont trails. He’s in the process of changing the name of the group to Belmont Plateau Cross Country Hall of Fame, and hopes to place a small “wall of fame” with race winners’ names near the starting line, at the bottom of the hill. Improvements to the trails—particularly navigational ones—could help the city bring in more regional championship races, Thomas hopes.

Dougherty was carrying a laminated topographical map of the Park that showed the various Belmont trails, but he took us off course as well. We peeked into the Greenland Nursery, where park plantings are born and nurtured. We stopped at the organic recycling center, where you can drop off leaves, grass clippings, and wood chips, and pick up compost for free.

We crossed and recrossed a petroleum pipeline that traverses City-owned parkland, which is probably a story for another day. We ran up against Interstate 76, which was platted across the woods and along the river in the middle of the last century, destroying Chamounix Lake and Chamounix Falls. The trail sidles up to the highway just above Greenland Drive, next to an overhead highway sign announcing the Montgomery Drive and Spring Garden Street exits, near mile 340.5. There’s a clearing in the trees, and it wouldn’t have been difficult to climb onto an exit sign and do pull-ups above the rushing traffic. Maule pulled up an app on his phone: 85 decibels of automotive noise, in what felt like the middle of the woods.

At the top of an incline, the trail split.

“This is where it gets a little murky, to me,” Dougherty said.

We found Chamounix Mansion, which was built in 1802 and has been run as a hostel since the 1960s. On the grounds outside the house, there’s a 200-year-old white ash tree. Maule wondered aloud about the word Chamounix, pronounced SHAM-uh-nee. Was it an old Lenape word, like the homophonic and nearby Neshaminy, that had been Frenchified by English speakers? (No. Just French, it seems.)

We walked back toward the Plateau along paved trails and roads. Dougherty told us that one of them, a long straightaway that’s now Chamounix Drive, had been used for an early form of drag racing, its paved side trail used for the return drive, in the days before the horseless carriage. It had to be dedicated as a separate trail, because the code of conduct for experiencing the Park at that time required that carriages be driven no faster than 7 miles per hour.

“Half the battle with park improvements, honestly, is just rediscovering what was already there,” Dougherty said.

Back in car territory, we crossed over a creek on a bridge that had very recently been smashed by a speeding vehicle. On a sharp curve where Chamounix Drive approaches Belmont Mansion Drive, shattered glass and broken car parts drew our attention to several dislodged large stones in the parapet, still dangling precariously.

Dougherty said the Conservancy’s plan for the trails was to make the park more “legible.” He talked about “perceptual barriers that really frustrate navigation.”

“These experiences are here for everyone,” he said.

Running and racing aren’t my preferred ways to experience the world. But I wondered whether I’d have been more inclined to walk into the woods when I lived closer to them knowing there were signs to guide the way.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.