Integration: What happens when magnet school suddenly drops admission criteria?

ListenFor many Philadelphia families, the city’s special admissions magnet schools are key resources that keep them from moving out of town.

But what would happen if one of these schools was suddenly required to drop its acceptance requirements and begin enrolling students performing at far lower academic standards?

One Northwest Philadelphia public school is on track to find out.

Demagnetizing a magnet

HIll-Freedman principal Anthony Majewski has been in a quandary over the past few years.

Parents at his high-performing specialty admissions middle school wanted the program to expand into a high school, but the building physically didn’t have enough space.

“I think we have one of the most amazing programs in the city,” he said. “However, to sell it – and not have a home – is very difficult.”

Majewski got the green light from the district to expand anyway – boosted by a grant from the Philadelphia School Partnership. But the solution was to put the high school kids in another building a mile away.

So last year and this year, he’s been running back and forth as principal at both.

“The feeling of community is rough,” he said. “I feel like I can’t really delve into the school when I’m jumping back and forth everyday.”

In October, district leaders came up with a new solution for Hill-Freedman, unveiled as part of a slate of changes that Superintendent William Hite promises will increase opportunities for 5,000 students at 12 schools.

Hite proposed closing nearby Leeds Middle School — a long-struggling school which accepts all-comers from the neighborhood — and moving the entire Hill-Freedman operation into the Leeds building.

But here’s where the proposal gets thorny for many Hill-Freedman parents: The 133 kids in Leeds’ current sixth and seventh grades would stay in the Leeds building next year and be mixed into the incoming classes of magnet school students.

“I have concerns, and I have questions,” said Sandra Carter, whose daughter is a current Hill-Freedman seventh-grader.

“I’m all for giving kids an even opportunity, and I do believe that there are some situations where some kids were not afforded an opportunity because of whatever — bad school, bad neighborhood, bad parents. But the reality is, my child tested to come in. And by testing, she had to meet certain criteria,” said Carter. “And I do have a question, as to, if you can’t meet those grades today, then why are you given an opportunity to come into this school?”

Integration

Unlike many debates about integrating schools, this one is not about race. Both schools have an overwhelmingly black student population.

But they do differ significantly in terms of economic class, which often translates into access to additional supports, early literacy proficiency and perceived school quality.

With its ability to select top students, Hill-Freedman stands far above Leeds when it comes to academic performance and school culture.

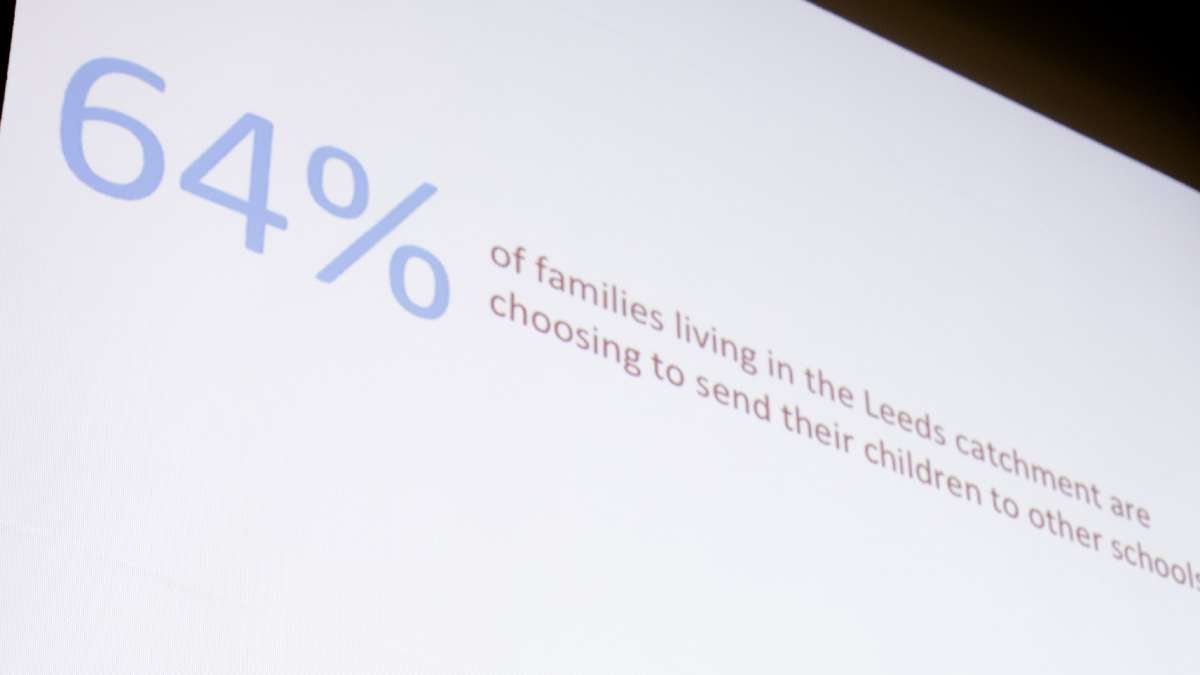

Hill-Freedman runs a blue-ribbon rated international baccalaureate program that regularly scores in the top echelon of district and state performance ratings. Leeds is ranked the lowest middle school on the district’s school quality index, and about two-thirds of the families in its catchment enroll their children elsewhere.

Last year, with 260 students, Leeds reported 22 violent incidents and 26 students who were suspended more than once – dwarfing the stats at Hill-Freedman.

“I’m not saying it’s everyone,” said Carter citing her own research into Leeds’ school culture. “But it concerns me that my child is going into that type of an environment.”

The central questions underlying this proposal are ones that have major ramifications for the larger education debate across the city, and even the nation:

Will the proposed merger boost academic performance of the neighborhood school kids? Leave them behind? Will it drag down the magnet school kids, or equip them with other valuable life skills?

Carter believes she already knows the answer. Before coming to the magnet school, her daughter attended A.B. Day elementary – an East Mt. Airy neighborhood school – where she was bored academically and frequently bullied.

“No matter what you do, sometimes, the circumstances of that child do not allow that child to rise to the occasion. And sometimes it has nothing to do with what goes on at school,” said Carter. “Sometimes it’s the support system at home. And you can’t fix that at school. You have to fix that in other ways.”

Many parents, Carter included, are frustrated that the district has not better involved them in the decision-making process. They plan to push back on the proposal and have been mulling the possibility of transferring their children into other school options.

Seventh-grade parent Lisa Corbin worries that the neighborhood school kids just won’t be able to keep up with Hill-Freedman’s rigorous, fast-paced curriculum.

“I know what my son went through when he first came here in sixth grade. Given a seventh-grade math book, it scared him to death. He thought that there was no way that he was going to be able to adjust,” said Corbin. “He’s a very good math student. It’s his favorite subject, and he was concerned.”

Inside the school, Principal Majewski has tried to convince his current students to welcome the Leeds community with open arms.

“‘We can do this,'” he’s said to students. “‘They’re human beings just like you, and as part of our IB community, we’re caring and respectful of all people and we’re going to make this work.”‘

Many Hill-Freedman students, though, have continued to express displeasure.

“I don’t like it, because I want to stay,” said seventh-grader Zaniyyah Ross, who feels “sad and irritated” by the proposal.

Eighth-grader Aarin Neilson said students fear the merger will spark violence.

“Everyone is really mad because they don’t want to collide with other students, because they think it’s going to cause a problem,” she explained.

A grandmother who declined attribution said her granddaughter has also been lamenting the change.

“She saying, ‘Well, Mom-Mom, I don’t think it’s fair. I really don’t think it’s fair for us. Are we going to lose what we have because of the other kids?’ she said.

“And she’s thinking in terms of behavior or whatever. It’s stereotyping. It’s not necessarily true, but that’s what she has in her mind.”

‘Iron sharpens iron’

There’s also a crucial flip side to this conversation. Many of the kids at Leeds have special-education needs in learning and emotional support – populations that the incoming magnet school staff are not used to serving.

At a hearing Tuesday night regarding the merger, one of the Leeds’ special-ed teachers, Maria Barracca, questioned the district’s strategy.

“Our most vulnerable students, many of whom come from extremely traumatic backgrounds, will not have the staff who have become their trusted, de facto counselors and social workers,” she testified. “Will these students be able to be incorporated in the regular education classes without feeling like pariahs because of their academic difficulties and behavioral needs?”

When Hite unveiled his plans for the merger, the larger questions raised by the entire prospect seemed to be the furthest thing from his mind.

In fact, he was fuzzy about some of the basic details – including Hill-Freedman middle school’s status as a magnet program.

“Is the grade school a magnet?” he asked, conferring with staff. “Yes, it is,” he added after a pause. “So it is, right.”

Not all parents, though, oppose the plan. Hill-Freedman also runs a special program for students with severe intellectual and physical disabilities, which includes Christy McMahon’s son.

“Iron sharpens iron last time I heard, right?” McMahon said in an interview shortly after the announcement. “So how do you make yourself better? You surround yourself with better people.”

At Tuesday night’s hearing, Terry Pittman, parent of a Hill-Freedman 10th-grader, praised the proposal. He thinks it will boost outcomes for the Leeds kids in the short-term while creating a fully fledged sixth-12th magnet option that will add value to Northwest Philadelphia in the years to come.

“You got it right,” he testified before Hite and several members of the School Reform Commission. “Hill-Freedman to Leeds is the right move.”

‘Do it right’

For his part, Principal Majewski seems to have only grown in his determination to make the transition as seamless as possible for all students.

In a poetic sense, Majewski said he’s driven to make the merger a success because Hill-Freedman is named in part for Samson L. Freedman, the only Philadelphia teacher ever killed by a student – an incident that happened in 1971 at none other than Leeds Junior High.

Through the years, parents have given Majewski high marks for his attentiveness, and Hite said that the merger can work, essentially, because of the principal’s leadership.

Majewski plans to ease tensions between the two student bodies through extracurricular team-building exercises, and he also plans to run a two-week summer academy to help the Leeds students adjust to Hill-Freedman’s academic and cultural expectations.

“Trust me. Trust us,” said Majewski, who’s committed to continuing as principal for at least another three years. “Trust us to do what’s best for your kids.”

The integration would continue only for two years, until the current Leeds students graduate eighth grade. After that, like all other students in the city, the students would need to apply and meet criteria to enter the Hill-Freedman high school.

Also as part of the plan, Leeds’ feeder elementary schools – Samuel Pennypacker and F.S. Edmonds – would grow to serve middle grades. This prospect will also require intensive support from the district.

In the district’s original plan, Parkway Northwest High School, which is currently situated in the Leeds building, would exist side-by-side with Hill-Freedman. Officials now say Parkway would move to the existing Hill-Freedman middle school property.

In an interview after Tuesday’s hearing, Hite pledged that he would give Majewski the resources needed to integrate students and serve the diversity of their needs, downplaying the fears of parents.

“People should give it the benefit of the doubt. So let’s see first how it works,” said Hite. “People predicted the sky would fall when we merged Germantown and MLK. The sky didn’t fall.”

The merger will be voted on by the School Reform Commission in February. In an interview after Tuesday’s hearing, chairwoman Marge Neff said she needed much more information about the district’s plan to support its proposal before she could make a judgment.

If the proposal is approved, parent Sandra Carter said she’s willing to give it chance. But nothing has yet convinced her that the district has both a comprehensive plan and the resources to execute it.

“It’s not being done at Central. It’s not being done at Masterman. Why is it being done here?” she said. “If it’s going to be done, then do it right.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.