In the beginning was the word, now on display at Penn Museum

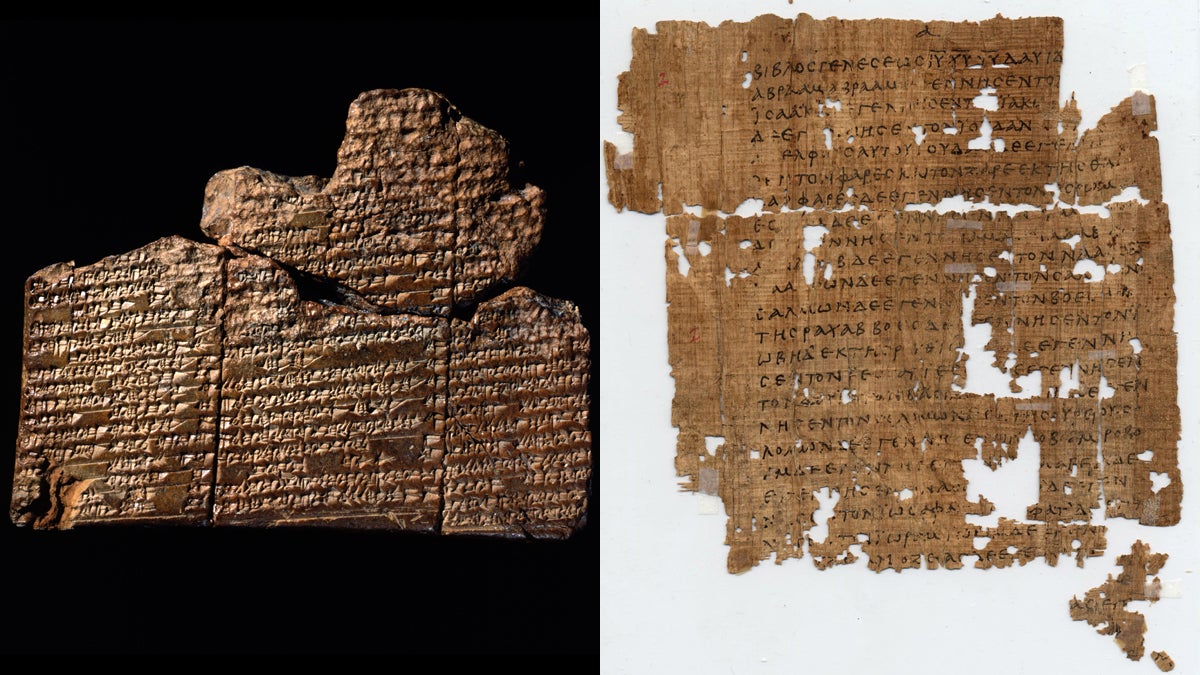

This ancient clay tablet (left) marked with cuneiform, a written language unique to ancient Mesopotamia, and a fragment of St. Matthew's Gospel (right), written in the 3rd century, are on display at the Penn Museum. (Images courtesy of Penn Museum.)

It is perfectly possible to celebrate Pope Francis’s September 26 arrival without wading into a gridlocked sea of humanity. Right now, before 1.5 million surge into the region, you can wander through August-empty streets to quietly marvel at Penn Museum’s Sacred Writings: Extraordinary Texts of the Biblical World.

It is a small but choice grouping: Just 10 documents culled from the archives of Penn Museum and Penn Libraries, representing numerous religious traditions across 3,600 years, all directed at drawing people closer to the divine.

Across ages and faiths, common themes emerge: humanity falls far short of the ideal, the supreme being is angry, prophets warn of disaster, often in the form of a flood. Whether by design or coincidence, it is a vision with particular resonance in Philadelphia as we await the papal apocalypse.

Texts echo across time

An amber-colored clay tablet is the oldest item on display. About four by six inches, it dates to 1650 BCE (before the common era) and contains the Mesopotamian account of a great flood in tiny Sumerian cuneiform script.

The theme recurs in an illuminated Qur’an inscribed almost three millennia later (1164). Two folios tell the story of Surah Nuh, a name equating to Noah, we are told, and a character who appears often to warn sinners of coming punishment though not, in this instance, a flood. Three centuries after that, medieval historian Werner Rolevinck documented the history of the world from creation to 1471, relating not only the story of Noah but also providing a schematic of his ark that showed where the plants and animals were stowed.

Noah is also on view in the youngest document in Sacred Texts: a bible created in 1999 by designer and illustrator Barry Moser, of which 400 copies were made. Open to the first book of Genesis, the facing page shows The Coming Deluge, a dramatic block engraving of Noah, sitting on deck, surrounded by crated animals, gazing over his left shoulder at the dark clouds.

Texts for study

Some texts were intended for scholarly research rather than religious ceremony, such as a 16th century Rabbinic Bible. Written in Hebrew and in book form, it allows space for commentary and is more easily handled than the scrolls used in synagogues. There is also a Polyglot New Testament (1599), written in a dozen languages, with passages printed side-by-side for ease of comparison, three languages to a page. In addition to the usual suspects such as Latin, Greek, French, and English, there are Syriac, Czech, and Danish. It’s fun just to figure out which language is which, and to find a common word to compare.

Texts for conversion

Aside from worship and study, religious texts are also intended to attract (or compel) new believers, and these are included as well. In New England, Puritan missionary John Eliot translated the Bible into the Native American language Massachusett, in order to convert its speakers to Christianity. Published in 1663, the Eliot Indian Bible is the first complete Bible printed in the western hemisphere. The copy on display is open to the first chapter of the Gospel of Matthew, which describes the geneaology of Jesus, beginning with Abraham and continuing through dozens of generations, a litany of ancestors linked by repeated use of the term beget. Judging by the frequency of wunnaumonieu in the corresponding Massachusett passage, that word must mean begat.

Strictly on appearance, an illuminated 13th century Latin bible is the most beautiful text on view. Words are thickly inked and touching, giving columns the appearance of closely woven cloth. Though almost impossible to read, the script is sublime to look at and to imagine printers curling over as the pages were created. Small bright illustrations leap out of the black-tendril strips, such as the Nativity, a postage stamp gathering of Jesus, Mary, Jesse, King David, Solomon, and the requisite angel, depicted in vivid colors and sharp detail, a nucleus of faith rendered in an inch-and-a-half square.

A contemplative antidote

Sacred Texts demonstrates the effort peoples of different creeds, cultures, and centuries have poured into recording what, why, and how they believe. Whether approached as theology, history, anthropology, or art, the documents are an oasis of quiet wonder, a contemplative antidote to the lamentable image of religion as a source of hurtful intolerance, reminding us of what faith can be for those who believe.

—

Sacred Writings: Extraordinary Texts of the Biblical World runs through Nov. 7 at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (3260 South St.).

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.