If Three Mile Island shuts down, counties could lose grant money

If Three Mile Island shuts down, the counties and communities surrounding the plant could see less money for emergency management.

Cooling towers at the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant in Middletown, Pa. (Matt Rourke/AP Photo)

This March marks the 40th anniversary of the partial meltdown at the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant. PA Post is collaborating with WITF and PennLive on a multimedia, monthlong look at the accident, its impact and the future of TMI and the nuclear industry. That includes new documentary television and radio programs, long-form audio stories, photos, and digital videos. The work will include the voices of people affected as well as community events to engage with listeners, readers and viewers.

—

If Three Mile Island shuts down, the counties and communities surrounding the plant could see less money for emergency management.

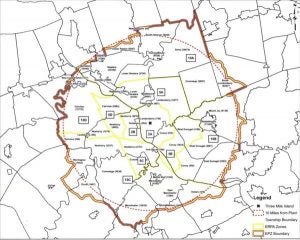

When other nuclear plants have closed, the operators have typically been given permission from the federal government to discontinue the 10-mile emergency planning zones. The counties and municipalities in those 10-mile zones receive money for emergency management purposes, including drills and educational materials.

Exelon Corp., which owns and operates Three Mile Island’s Unit 1, has said it intends to shut the plant down this year. Lawmakers are working on remedies to keep the plant operating.

“Without a policy solution, the ripple effect of the early retirement of Three Mile Island Unit 1 will be felt throughout the community,” Exelon said in a statement.

“Several county and state emergency management positions will no longer be funded by Exelon Generation when TMI is decommissioned,” Exelon said.

Exelon said its TMI decommissioning plan is still being developed but the company will “maintain the necessary corporate emergency management organization, practices and procedures throughout shutdown and decommissioning process.”

In 2018, Exelon paid $425,000 in fees from TMI to the Pennsylvania Emergency Management Agency. If the plant is shut down and the 10-mile emergency planning zone is scrapped, the state would have fewer costs, since there would be fewer drills and training exercises, said Paul Vezzetti, a spokesman for PEMA.

If TMI is shut down, PEMA would negotiate with Exelon “to determine an appropriate level of funding based on the remaining threat,” Vezzetti said.

Eric Epstein hopes the emergency planning zone isn’t dropped anytime soon, even if the plant is shut down.

Epstein is chairman of Three Mile Island Alert, a group that has long been critical of the plant and nuclear energy. Epstein said he hopes emergency planning and education efforts continue in the 10-mile zone for the foreseeable future.

“We are strongly advocating the emergency preparedness zones be maintained,” Epstein said.

Residents within 10 miles of the TMI receive regular mailings and information on how to respond in the event of an accident at the plant. Every two years, emergency officials from across the region conduct a drill on how to respond to a disaster. The bi-annual drill takes place again this year.

Even if the plant stops operating, Epstein said there are plenty of reasons to continue drills. Nuclear waste will remain in storage on the site, and potential hazards include fire and nuclear threats.

“It’d be folly to think the danger is erased because the plant is not operating,” Epstein said.

PEMA distributes grants to host counties for emergency planning related to TMI.

York County, for example, received $58,000 last year, said Mark Walters, a county spokesman. The bulk of the money goes to communities and school districts for training and equipment. York County is part of the emergency planning zones for two plants: TMI and Peach Bottom.

Exelon also reimburses surrounding counties for the costs of employing nuclear planners, Walters said.

Exelon sought to discontinue the 10-mile planning zone when it shut down the Oyster Creek nuclear plant in New Jersey last year. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission, which oversees the nation’s nuclear plants, approved Exelon’s request.

The 10-mile emergency planning zone was also scrapped after the Vermont Yankee nuclear plant closed. The plant ceased operations in 2014 and federal regulators allowed the 10-mile zone to be ditched in 2016.

Neil Sheehan, an NRC spokesman, said a request to amend emergency plans and abolish the drilling in the 10-mile zone typically comes after a plant ceases operations. The NRC closely reviews such applications, Sheehan said.

“They would have to make that case and we would have to look at it,” Sheehan said.

When a nuclear plant shuts down, the risk of a radiation release off-site is dramatically reduced, Sheehan said. The main concern would be with a problem with the container holding spent nuclear fuel. As the fuel cools, the risk of fire and a discharge of radiation plunges, Sheehan said.

The speed at which the spent fuel cools would help determine when emergency drills and preparation efforts inside the 10-mile zone would no longer be deemed necessary, Sheehan said.

Dan Scully, deputy director of emergency management for Lancaster County, said when the plant is no longer operating and the reactor is emptied, “There is no threat.”

On the downside, emergency planning agencies receive funding for training exercises at TMI that also helps communities prepare for any number of disasters, Scully said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.