‘I kill plants so others may thrive’: Removing invasive species one painstaking patch at a time

A crew of dedicated volunteers removes wineberry and other invasive plants that choke out native species and harm the ecosystem in White Clay Creek State Park.

Listen 4:35

Katherine Evers, assistant park superintendent, said the work has helped the native seed base return. (Cris Barrish/WHYY)

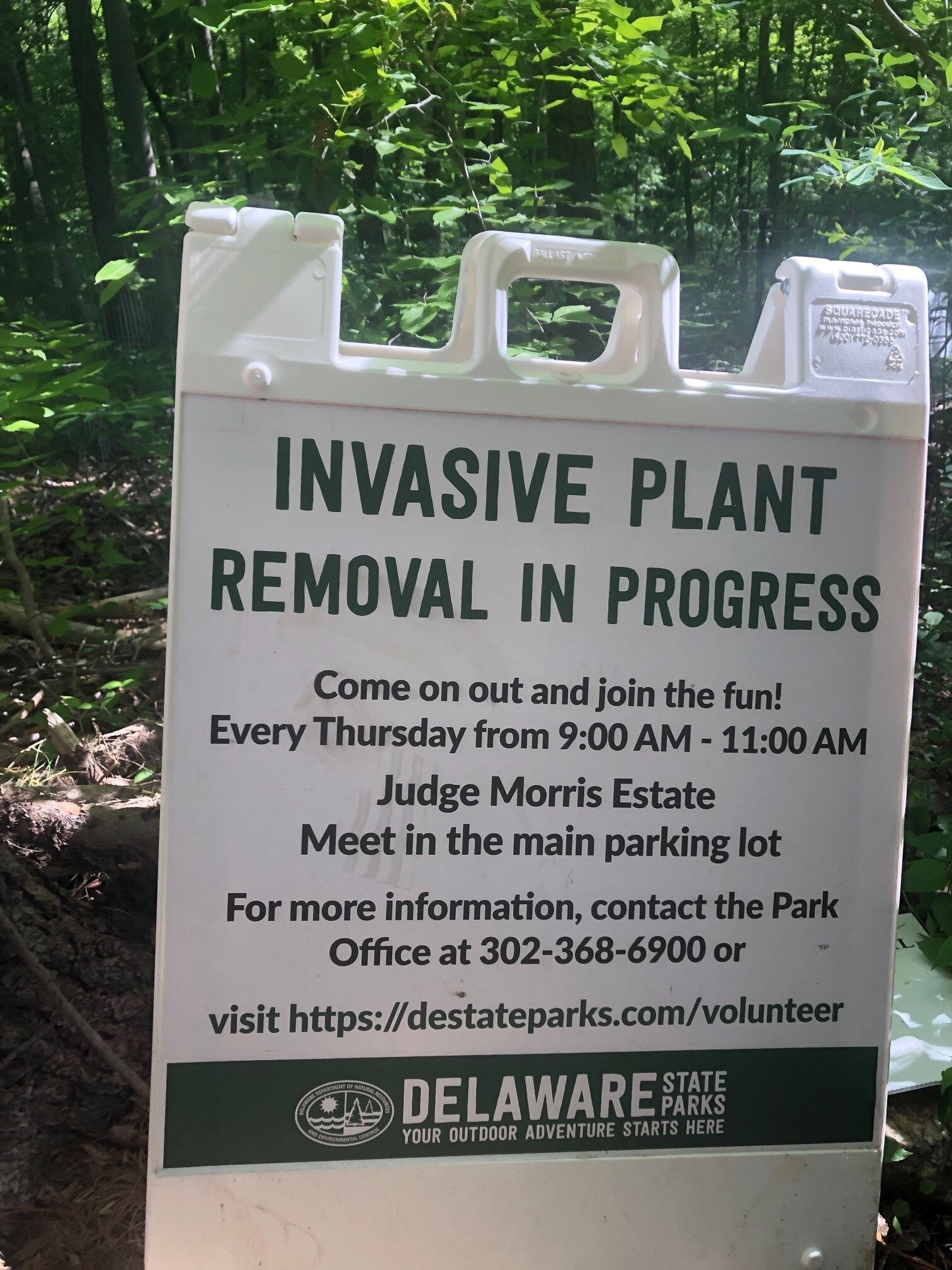

Terri Tipping gathers her troops in a masked, socially distanced huddle in the parking lot of the Judge Morris Estate in Delaware’s sprawling White Clay Creek State Park.

“What are we pulling today?’’ someone asks the retired certified public accountant.

The bespectacled Tipping has the bearing of a soft-spoken football coach while addressing the dozen or so people wearing long pants and thick gloves, wielding shears and other tools. One guy shoulders a pickaxe.

“The game plan is, same area as last week,’’ she says. “We’ll hit a wineberry area and we’re mostly trying to keep the edge clean because of all the seedlings planted. We’re trying to preserve those. We need some rain, but let’s at least clear the multiflora and wineberry from the edge. All right, we’re good to go.”

The group treks up a dirt trail to a dense woods with a single mission: clearing invasive plant species that have overtaken sections of the park, to the detriment of the native plants and the birds, deer, squirrels, bugs and other creatures that inhabit the natural area and need them to survive and thrive.

Consider the wineberry patches the group tackled Thursday when WHYY visited. The plant has tasty fruit that deer and other animals love, but it’s not nutritious.

And there’s other species that aren’t appetizing.

“A lot of these non-native plants have formed monocultures and we will walk through them and see that there’s no insect chews,’’ Tipping tells WHYY. “The deer are not touching these plants. So we know that it’s not providing any food for the critters. So we’re hoping that by removing these, it can then give the natives an opportunity to come back. And that would provide the food for the insects and the deer and the birds and things.”

Chris Bennett, environmental stewardship manager for state parks, said the vast majority of the invasive plants came from Asia and Europe for landscaping purposes.

Delaware lawmakers are also targeting invasive plants, recently enacting a law that forbids selling, importing, or planting them. It takes effect next year.

But the hard work is on the ground, where the roots meet the soil. The laborious removal project began four years ago with Tipping and just a few other park-lovers. But now some 100 volunteers participate when they can, never stopping, even when the coronavirus pandemic struck Delaware 14 months ago. They meet every Thursday and Sunday morning for two hours. Everyone is welcome, as long as they don’t mind getting a little dirty.

Tipping calls their work a “Sisyphean task,” referencing the tale from Greek mythology of gods condemning a king to forever push a boulder up a hill, only to see it roll back down.

She says that’s what it takes: constant, consistent clearing — even as the invaders take root and try to spread — to preserve the flora and fauna ecosystem of the 500-acre section of the park near Newark that’s a magnet for hikers, dog-walkers, joggers, and bicyclists.

The work is especially critical since last month volunteers planted 4,000 seedlings that need time and space to grow and prosper, Tipping said.

She said the work is what every backyard gardener tackles, but on a grand scale. “It’s kind of like weeding the forest,’’ she says.

Katherine Evers, assistant park superintendent, says the contribution of the volunteers is vital.

“There is a big presence of invasive plants and I’m really, really grateful for this group that comes out and helps us get rid of it. Because as you hike through Judge Morris, you can see the areas that we’ve tackled over the past five years.

“And just this little group coming out two hours, twice a week has been enough to make an impact to see the native species rebound. You can see the whole native seed base coming back. It’s just been phenomenal.”

‘Birds don’t have insects to eat and nutritious berries’

Once in the forest, the volunteers spread out. A couple of students from the University of Delaware pull non-native strawberry plants. The others are pulling and clipping at the swaths of wineberry.

One is retired ceramic artist Peter Saenger. “I’m more of a restoration forester anymore,’’ he deadpans.

Saenger snaps a plant from the soil. “This is a wineberry. You can tell by the fuzzy red hairs on the stem. … It’s got delicious berries. It’s part of the problem. It’s so good to eat,’’ he says, launching into a tutorial for those nearby, including newcomer Bill McGonegal, who joined after retiring as a state health and social services administrator.

“The birds love this stuff,’’ Saenger explains. “The problem is that the fat content in the invasive berries isn’t as good as the native ones. So the food value is less.

“And another problem is that the caterpillars and the bugs don’t like to eat the invaders, which means that the mama birds have fewer caterpillars to feed to their babies. And it’s the caterpillars that are full of lots of calories and they’re nice and soft. So when mama bird shoves them down their babies’ gullet, you know, they’re fed.”

Nearby, swinging a pickaxe and wearing a blue T-shirt that proclaims, “I kill plants so that others may thrive” is veteran volunteer Mike Czupryna. He’s an avid mountain biker who’s retired from his career as a pharmaceutical firm manager. He also volunteers to maintain the park’s winding system of trails.

“Removing the invasive plants makes a big difference,’’ he says, quipping that it’s also “a reason to get out of bed on a Thursday morning. But really, it’s great to see the progress.”

Czupryna acknowledges that it’s sometimes difficult in a sea of green plants to distinguish the invaders from the natives.

“We discovered a couple of years ago that some of the viburnum that we thought was the bad viburnum was actually a good viburnum,’’ he says. “And so we had a hard time making sure we were not pulling the wrong ones. So that’s all part of the education.”

And while volunteers say they’re always wary of ticks and the potential to contact Lyme disease — hence the long pants — and that an occasional non-poisonous snake is discovered while clearing a patch, Czupryna says some also have “come across a hive of yellowjackets” and been stung.

Tipping says she’s had people who aren’t park visitors or nature lovers ask her about the value of removing plants that are spreading naturally, regardless of their origin.

Her response?

Scientists and academics “talk about how the food web is broken when they see the decline in the numbers of birds and things like that,’’ she says. “And if the birds don’t have the insects to eat and the nutritious berries to eat, then your non-nature lovers seem to notice the decline in birds and things.”

For Saenger, clearing the brush and the weeds is simply a joy.

“I love being in the forest. I find it very therapeutic, really, to come in and see the sights and sounds,’’ he says. “And then to be able to do some volunteer work on top of that just checks a lot of boxes for me.

“You can sort of give back doing this kind of work in addition by subtraction. You’re taking material out and you’re helping the forest by getting rid of the freeloaders who are taking the resources, taking the sunlight, taking the water.”

Tipping says she’s guardedly optimistic that in the long run, the work will benefit both park users and its inhabitants.

“We’re just constantly going to be battling these and to see if it makes a difference, eventually,’’ she said.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.