Philly arts college owners accuse CEO of embezzling millions in lawsuit, blame financial ruin on execs

Hussian College owners are seeking $162 million in damages, claiming executives enriched themselves with unauthorized bonuses while the school plunged toward closure in 2023.

Listen 1:03

The former for-profit arts school Hussain College operated inside 1500 Spring Garden St. until its closure in May 2023. (Kristen Mosbrucker-Garza/WHYY)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

The private art school Hussian College in Philadelphia closed after a financial collapse in 2023.

At the time, the abrupt closure was blamed on the COVID-19 pandemic and low student enrollment.

In May 2020, the school had 1,435 students and $35 million in gross revenue. That dwindled significantly until its closure in May 2023.

Years later, the owners of Hussian College claim its financial issues were the result of a coordinated scheme by its own executives and business lenders to defraud the business and embezzle $4.1 million, according to a lawsuit filed in Philadelphia Common Pleas Court in September 2024.

The case has since been kicked up to the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania.

Businesses can use the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act in civil lawsuits to recoup money lost to organized white-collar crime. In Rico cases, plaintiffs can request three times the value of the damages, and the college’s estimated value was $54 million.

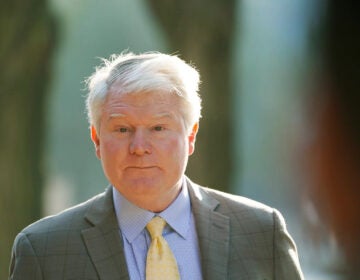

So Hussian College’s owners are seeking a whopping $162 million in damages from several former executives, including CEO Jeremiah Staropoli, court records show.

The alleged scheme involved executives creating fake email addresses to enter into high-interest business loans with Velocity Capital Group and Summit Capital Funding to provide stop-gap funding until tuition money would come in from students. Then, they would pay themselves secret bonuses.

School executives are also accused of defrauding students of their credit balances, not returning unearned federal student aid, failing to pay building rent, and putting employees on multiple furloughs without pay, according to the lawsuit.

Staropoli’s defense – filed in mid-January – is that his executive contract requires the college to submit to arbitration instead of a civil court case to settle employment disputes.

Neither representatives of Hussian College nor its executives’ attorneys responded to comment for this news story.

Law professor Michael Mears, of Atlanta’s John Marshall Law School, said that the arbitration defense is not likely to hold up in court because it’s not a breach-of-employment-contract lawsuit but a RICO case.

“Across the country, we’re seeing RICO being used more and more as a civil remedy,” Mears said. “If you’re talking about contractual obligations that could be handled under arbitration, but not in this case because they’ve taken this case under the RICO statute.”

This case will likely take several years before a judgment is rendered. The next big step will be discovery, where emails detailing the alleged scheme could be uncovered.

“That’s where it’s going to be very damaging to the defendants,” Mears said about the possible emails. “Because it certainly shows criminal intent if you transmit false information through the mail, and that would include email under most state laws.”

Hussian College began in 1946 as a vocational fine arts school for U.S. military veterans returning from World War II to Philadelphia. It was named after its founder, John Hussian.

In 2011, the college was acquired by investors, including Joshua and David Figuli.

In 2019, the pair hired Staropoli as a consultant, then CEO of the college, with a base salary of $225,000, which would increase by $25,000 each year. Staropoli was eligible for performance bonuses of up to 50 percent of his base salary – in the first year, that would have been a maximum of $112,500.

In 2023, Staropoli was earning a $350,000 base salary. He gave himself a total of $643,136 extra in bonuses between 2020 and 2023, according to the lawsuit.

Staropoli was also accused of racking up $36,747 on the college’s credit card for vacations to Disney World and Nashville, dues at DuPont Country Club in Delaware, and tuition for executive Adrienne Scott at Drexel University, according to the lawsuit.

All that time, the college’s finances worsened.

Under the CEO’s leadership, the college’s net revenues declined from $25.7 million in 2020 to $14.5 million in 2023. The executives are accused of paying themselves $4.1 million in salaries, benefits and secret bonuses during that time period.

“Defendants concealed the payment of the illicit bonuses by not accounting for them in the cash flow statements and business plan projections presented to the board of directors, nor the approved budgets,” wrote Alan Fellheimer, attorney at Leech Tishman Fuscaldo & Lampl LLC in Philadelphia.

Even if the lawsuit succeeds, don’t expect all that money to come from the individuals charged.

Often, embezzled money is already spent by the time of a judgment. Instead, payment could come from personal insurance policies held by executives for liabilities.

Mears also said that the insurance companies of the lenders who allegedly participated in the scheme could pay the majority of the costs.

“I suspect there’s an insurance company working in the background somewhere with these two corporate defendants in this case,” Mears said. “So we might be looking at the limits of liability to these businesses’ insurance.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.