How do you defend against measles? Stand ready to fight the disease like the enemy it is

Standing ready to fight measles like an enemy is the best defense, health care experts say. Here’s how one hospital and school district have prepared.

Listen 5:06

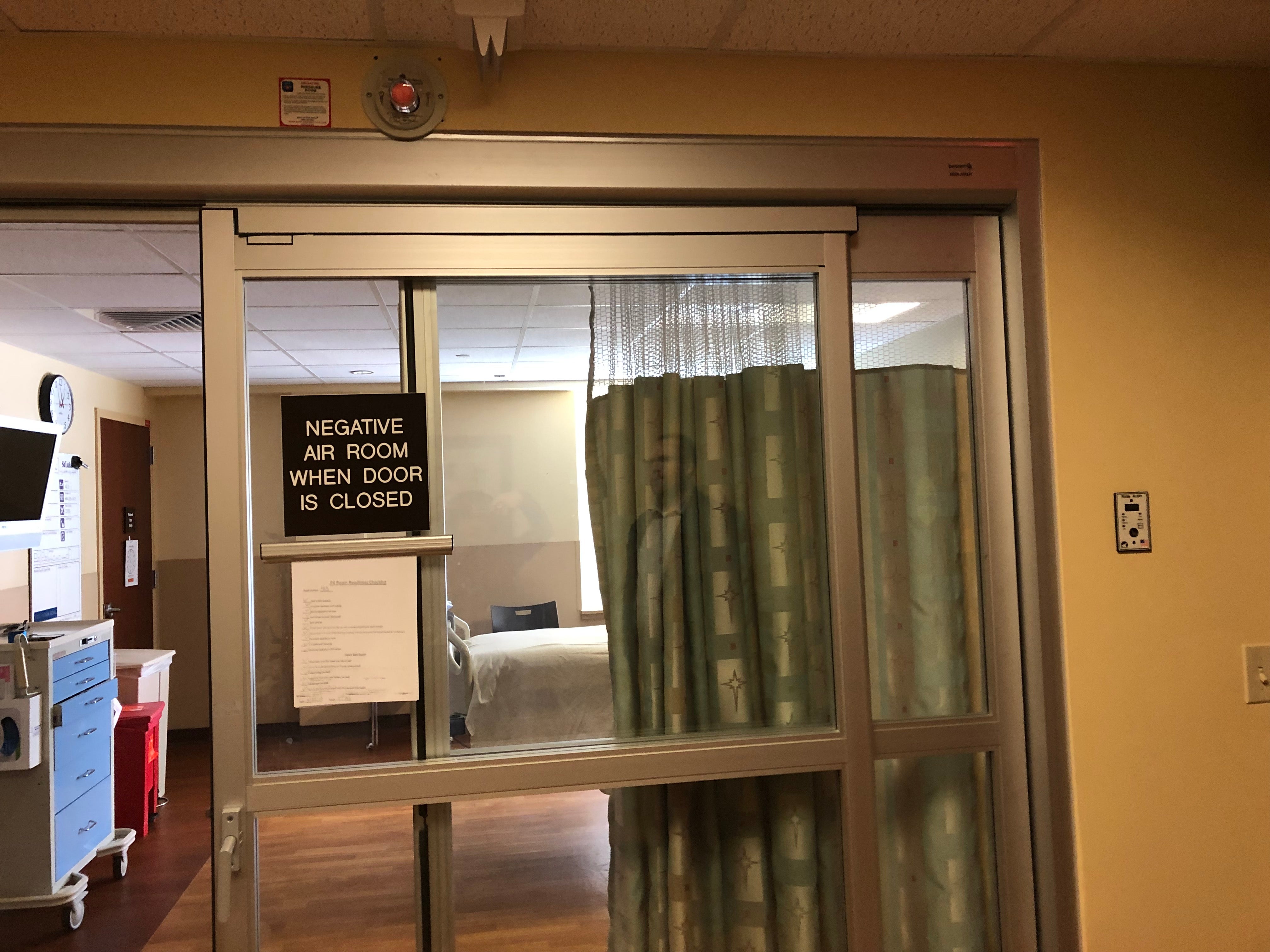

Inside the negative pressure isolation room at St. Luke’s University Hospital. Vent in the upper right filters contaminated air in the room. (Christine Fennessy for WHYY)

This story is part of our Modern Kids series.

If a child shows up at St. Luke’s University Hospital in Bethlehem with symptoms of a highly contagious disease, she goes into a negative-pressure isolation room such as the one on the building’s fourth floor, in a critical-care area of the hospital.

This year, of course, the contagious disease on everyone’s mind is measles. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention cites 880 confirmed cases as of May 17, in 24 states including New Jersey and Pennsylvania. That makes 2019 the worst year since 1994 for measles, the CDC says. Back in 2000, the disease was declared eliminated from the United States.

When it comes to measles, precautions are imperative. The measles virus lives in the nose and throat. When an infected child coughs or sneezes, millions of virus particles escape into the air. And they can linger for hours, potentially infecting others.

(Christine Fennessy for WHYY)

At St. Luke’s, the isolation room is almost entirely fronted by glass, offering an unobstructed view of the patient inside. A wall-mounted monitor to the right of the sliding glass door indicates the room’s air pressure.

The air pressure may be neutral, meaning there’s no directed air flow.

It may be positive, meaning air is flowing out of the room and into the hallway. If a young patient inside the room has a compromised immune system, positive air flow protects her from contact with pathogens in the hospital.

Or the air pressure can be negative, which means air can’t escape the room.

“You want to contain the droplets and the airborne particles inside the room,” said Lori McSorley, manager of infection prevention for St. Luke’s. “So with negative air flow, the air only goes into the room instead of out, and it goes out of the room through a special HEPA filter in the ceiling, which kills the organism.”

On the other side of the glass door is a slot into which, when the room is occupied, staff slides a blue warning sign signaling an airborne infection. The sign directs all visitors to check in, wash their hands, and put on close-fitting surgical masks.

“Before you would even enter the room, you would put on your personal protective equipment, or we refer to it as PPE,” said McSorley. “Specifically, you have to have on an N95 respirator, which filters out 95 percent of particulate matter.”

Such measures are standard for St. Luke’s when it comes to protecting the community against the spread of viral, airborne diseases like chickenpox, mumps, the flu, whooping cough, and measles.

Facing down a devastating adversary

“Measles is the most contagious disease, right now, that mankind has,” said Jeffrey A. Jahre, an infectious-diseases specialist and senior vice president for medical and academic affairs for St. Luke’s University Network. In fact, “90% of individuals who are not vaccinated or who are not immune who are exposed to a measles case will come down with measles.”

And the effects, he said, can be devastating.

“It’s not just the disease itself,” said Jahre. “One in 10 individuals will develop major ear infections, and some result in deafness. Perhaps one in 20 will develop pneumonia. One in 1,000 will develop encephalitis that can cause severe brain damage. There can be a type of brain disorder that can happen many years later, as well as various other bacterial and viral complications. And the virus itself can cause death. So it’s not a disease to be taken lightly.”

Prevention, he said, is always better than the cure.

To that end, St. Luke’s does a lot of educational outreach in the local community about the importance of vaccines. Not just for measles, but for all vaccine-preventable diseases.

It also runs a busy community health program that works hard to address the concerns of vaccine-hesitant parents and provide a safe space for parents to express their opinions.

Better prevention, however, requires not only a more informed public, but a savvier medical community.

“If you look at the physicians that are now practicing, the vast majority have not seen a case of measles,” Jahre said.

Symptoms of the virus include red eyes, runny nose, cough, sore throat, and high fever. If you don’t know what to look for, it can be easy to mistake measles for the flu, or a bad cold.

“You have to have people recognize the disease in order to identify it correctly,” he said. “And so we are in the midst of a very active program of educating our first-responder physician community.”

The program includes a tabletop exercise, scheduled for Wednesday, in which participants will talk about the signs and symptoms of measles, how they would handle a sudden influx of patients, how they would get information out to the public, and how they would screen visitors.

It’s essentially establishing an incident command center, said McSorley, the hospital’s manager of infection prevention.

“It gets you set up for disaster preparedness,” she said. “For example, if you had an influx of three to five cases within a certain period of time.”

Then participants in the exercise will share what they learn.

“This is what I would call a team sport,” said Jahre. “When you have an outbreak in a community, it’s not one health system. One of our major educational efforts is not only to make sure that people within our network are educated, but that we have a good cooperative spirit with all of the other health care providers in the area.”

In the trenches: School nurses

If disease prevention is a team sport, school nurses are starting players on the offensive line.

Kathy Halkins is a school nurse at Liberty High School in Bethlehem and the supervisor of health services for the 14,000-student Bethlehem Area School District. She’s been there for more than 30 years, and she knows the vaccine status of every kid in the public schools.

School nurses across the state work hard to make sure all kids are immunized, Halkins said.

“And we’re like pit bulls,” she said. “If we have a child that needs help, we’re going to go help them. Because a child that’s not healthy has difficulty learning, and our goal is to get everyone in the classroom and to learn.”

That work includes hosting a big clinic at Liberty High School in September where kids can get any shot they need for free — measles, mumps, rubella, chickenpox, polio, hepatitis B — even if they don’t attend the district’s public schools.

“Anything they need, we’ll have it for them,” she said.

Later in the fall, they do free drive-through flu shots. They work with pediatricians on behalf of students, help parents book appointments at free local immunization clinics, and, in some cases, even give kids shots right in school.

Pennsylvania law says all kids have to have a distinct set and number of vaccinations to attend school. For example, and among others, a child needs four polio shots, three hepatitis B shots, and two for measles, mumps, and rubella.

During school registration, Halkins said, “we ask [parents] for proof of their child’s vaccinations with the dates they had them. Shots need to be given a certain length apart. So if you get a measles shot and two days later get a chickenpox shot, the chickenpox shot doesn’t count. They have to be spaced 30 days apart. So we need to know dates and types of shots to verify they were given appropriately.”

If a child has at least one dose of every vaccine, he can be provisionally enrolled, said Halkins — meaning he can go to school as long as his parents follow an approved plan for when and where he’ll get the rest of his shots.

“As long as you follow your plan, you may stay in school,” she said. “But if you miss an appointment, you’re out until you get it taken care of.”

Those are the requirements. No matter where the child goes to school.

“It doesn’t matter if you’re public, private, if you’re a Catholic school, if you’re a cyberschool, if you’re home-schooled, you still have to show proof that you’ve had the shots or you have to sign an exemption sheet that you don’t believe in them,” she said.

Like all states, Pennsylvania allows parents to claim medical exemptions to vaccines. And like nearly every state, it allows for religious exemptions. But the commonwealth is one of just 17 states that also allows parents to claim philosophical exemptions.

Among the 2,800 students at Liberty High School, Halkins said a handful aren’t vaccinated. Some have medical exemptions, she said, and the rest have parents who are philosophically opposed to vaccines. During school registration, the nurses do what they can to explain the importance of the shots.

“We also make sure they understand if there was to be an outbreak of measles, their children wouldn’t be able to come to school for probably close to a month,” she said.

Philosophical exemptions are rare in the Bethlehem school district, she said, and the vaccination rate is extremely high. In fact, according to Halkins, the average vaccination rate of Bethlehem public schools is 97.48%.

She recently reviewed the vaccination records of every noncompliant child, talked to the nurses in their schools, and got those kids — most of whom were newly enrolled in the district — caught up.

“The numbers were small, but I don’t care if it’s only two kids, it’s still two kids,” she said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.