How did pension systems in Pennsylvania’s cities get in such bad shape?

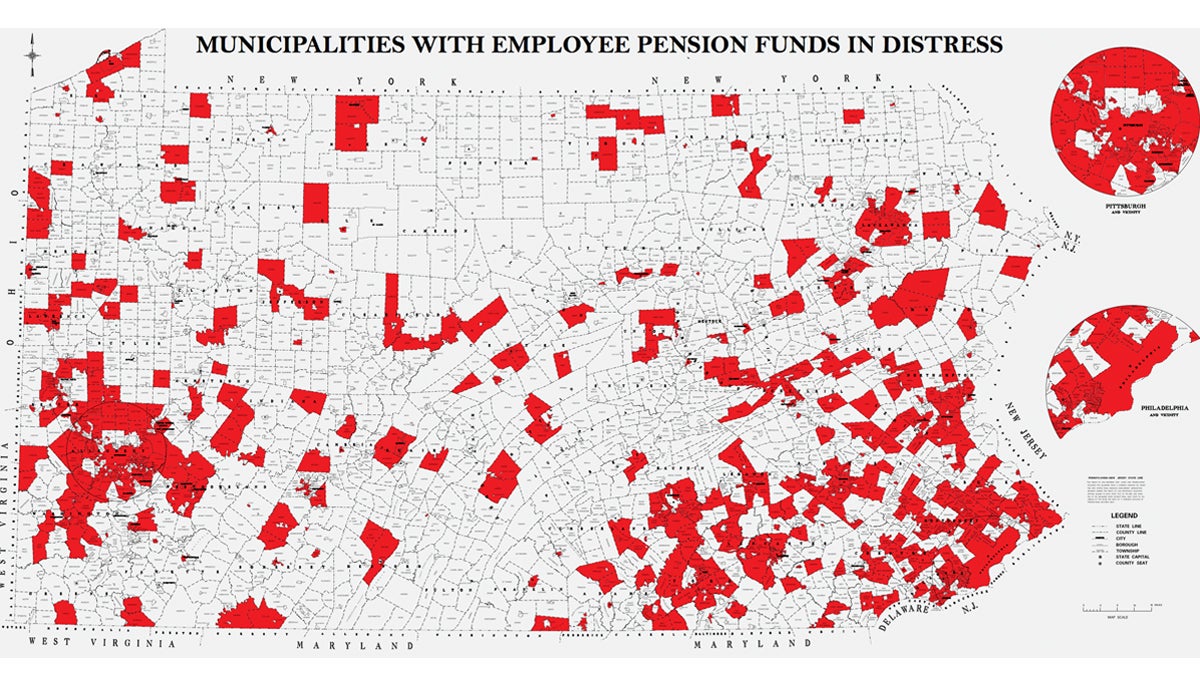

Map of Pa.’s municipal pension funds in distress from the Pennsylvania Auditor General’s office.

Seeking a better understanding of Pennsylvania’s issues and proposed solutions? Sometimes, complicated jargon and concepts can get in the way. That’s why we started Explainers, a series that tries to lay out key facts, clarify concepts and demystify jargon. Today’s topic: Pensions.

One in a series explaining key terms and concepts of Pennsylvania government. Today’s topic: Pensions.

Here’s how pensions are funded: The government and its workers stow away money every year. Then that money is invested on Wall Street.

At least, that’s how it’s supposed to work. Pension systems across Pennsylvania are in lousy shape, in large part, because cities have simply refused to make the annual payments that actuaries recommend to keep their pension plans in good health.

As The New Yorker’s James Surowiecki put it, “Politicians are adept at rationalizing such irresponsible behavior. When markets are up and pension funds are flush, they say that there’s no need to add money. When times are bad and tax revenue drops, they say that they can’t afford contributions.”

Case in point: The Pennsylvania General Assembly gave permission to cities to reduce or halt payments into their pension systems during the Great Recession.

To make matters worse, many Pennsylvania cities and towns have been too optimistic about how much their investments would earn in the markets. Many pension investments especially took a hit during the recent economic downturn.

The Pennsylvania Auditor General’s office also blames cities’ underfunded pensions, in part, on outdated retirement laws. In the 1930s, the average U.S. life expectancy was 60 years old, so local lawmakers allowed employees to retire when they were 50.

The average life expectancy today is almost 80, but politicians in some Pennsylvania cities have not updated their allowed retirement age. That means those governments are on the hook for 30 or 40 years of retirement benefits, instead of the original 10 or 20.

What role do overly generous retirement benefits play in the municipal pension funds’ problems?

According to the Pew Charitable Trusts: “Pew’s analysis suggests the generosity of benefits does not explain why some [U.S.] cities’ pensions systems were better funded than others. Instead, what was more important was whether cities increased their retirement benefits but failed to set aside enough money to cover them.”

The average annual pension payment for public employees in the United States is $22,600, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. Not exactly lavish.

Sometimes municipal workers can sweeten their retirement benefits, however, through a controversial practice known as “spiking.” This is when an employee uses overtime, unused sick time or unused vacation days to inflate their salary in their final years of work. That figure is then used to calculate annual pension payments.

This can have a negative effect on pension systems. In 2013, Allegheny County found that just 30 workers who “spiked” their benefits were costing the government an extra $1 million annually.

Did this article answer all your questions about pensions? If not, you can reach Holly Otterbein via email at hotterbein@whyy.org or through social media @hollyotterbein. Have a topic on which you’d like us to do an Explainer? Let us know in the comment section below, or via Twitter @Pacrossroads.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.