How 25 years of changing enrollment has created winners and losers in Pa. school funding

Listen

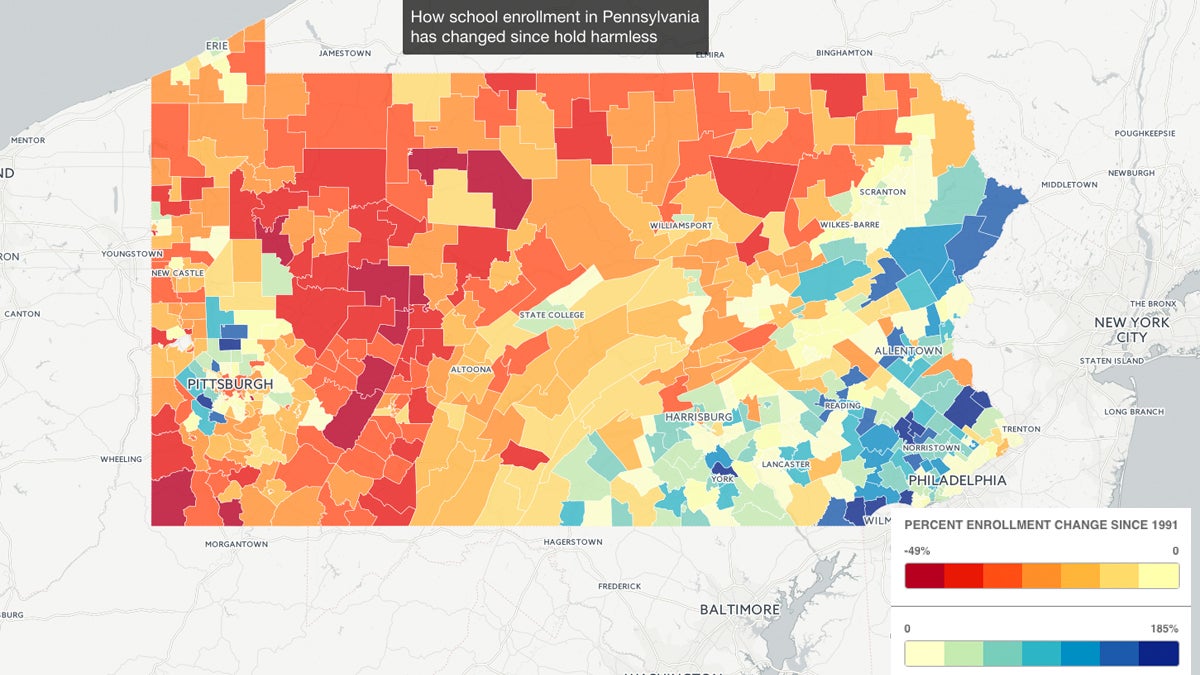

How school enrollment in Pennsylvania has changed since hold harmless policy. (Map by Rachel Feierman)

School district enrollment levels have dramatically shifted in Pennsylvania over the past 25 years.

Many rural districts in the western part of the state have seen steep declines, while many urban, suburban, and eastern districts have grown. In all, more than a third of the state’s 500 districts have either grown or shrank by more than 25 percent since 1991.

That was the year the state implemented a “hold harmless” policy, which dictated that enrollment fluctuations would not affect state funding allocations. So, for decades, all districts received the same inflationary boost to funding no matter if, for instance, they gained or lost hundreds of students from year to year.

Over time, this has greatly affected the equity of the state’s school funding. And for those on the losing end, this contributed to decades of strife.

As detailed in a previous Keystone Crossroads analysis, “hold harmless” has been a major boon for districts where student population has declined, and has been a major challenge for many of the districts where enrollment has spiked.

Growing pains

Eighty-six school districts have seen their student populations grow by 25 percent since 1991.

Many of these are wealthier, suburban and exurban districts, but some are among the poorest in the state.

And it’s to these districts that state policy has been most cruel.

Reading, Allentown and Lebanon have seen tremendous population growth while being tasked with serving some of the poorest, most needy students in Pennsylvania.

But the state has not systematically acknowledged these burdens or the enrollment spikes.

“It’s created a confluence of issues with educating our students,” said Reading superintendent Khalid Mumin. “It’s not adequate.”

This year, though, lawmakers implemented a student-weighted funding formula in order to add more realistic factors to its funding distributions.

This begins to rectify the logic of the past.

But even with the formula in place, districts historically shorted will continue to struggle. Lawmakers only plan to use the formula — which counts factors such as actual enrollment, poverty and language fluency — to disperse only new increases in state aid.

Currently, that means 94 percent of the pot of state basic education funding ($5.5 billion) is still distributed without taking enrollment or other student-based factors into account.

Of the 168 districts where enrollment has risen by five percent or more since the state enacted “hold harmless,” 13 serve among the poorest students in the state.

They are Allentown, Carbondale, Erie, Hazleton, Lancaster, Lebanon, Minersville Area, Panther Valley, Philadelphia, Reading, Scranton, Shenandoah Valley, and York.

Of these, only York cracks the top 25 in per-pupil state basic education funding.

Philadelphia specifically was hurt in the first few years of hold harmless, as it added tens of thousands of new students without any systematic acknowledgement from the state.

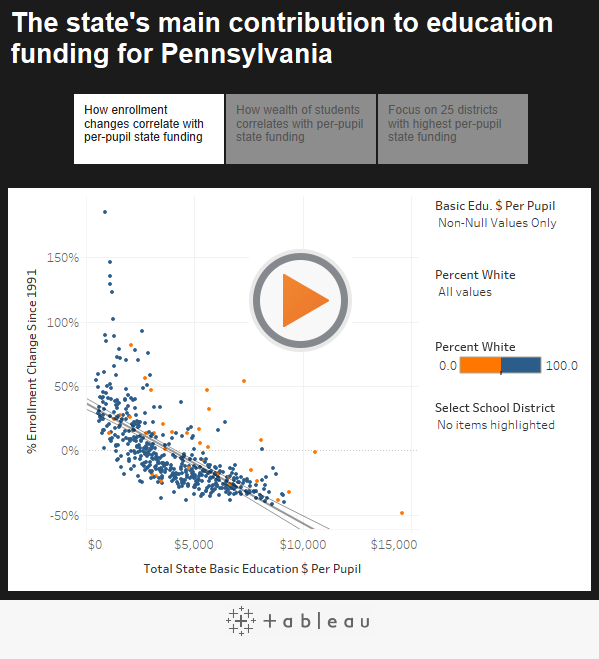

There are three interactive graphs below, and you can toggle from one to the other by clicking on the tiles near the top. You can use the sliders to zoom in on certain data.

As shown in the first graph, there’s a clear correlation between enrollment change and per-pupil state basic education funding.

The second graph shows the relationship between wealth and per-pupil funding, while the third focuses on the districts getting the most per-pupil funding from the state.

//

In Reading, poverty rates have risen over the past two decades, with median household income now under $27,000. Rates of english language learners have also grown, now comprising over 18 percent of students in the district.

At the same time, total public school population in Reading has grown by 54 percent since 1991.

Without a student-based formula systematically acknowledging these changes, Superintendent Mumin says, his district has been at a disadvantage.

“You’re seeing a lot of teachers, but I would say, not enough,” he said. “You’re seeing counselors and counseling services, but not enough. I think we need more.”

It’s important to note that this analysis mainly concerns the basic education subsidy, which is the state’s largest budget line for public schools. Districts also receive monies from other state budget lines as well as from local and federal sources.

In theory, the basic education subsidy is meant to help level the playing field among wealthy and poor districts, and so the logic behind how this money is divided is important.

Reading is case in point. The city district relies on the state for almost 75 percent of its funding, but because the weakness of the local tax base, Mumin says he still can’t afford to support adequately the deep needs of his students.

Effect on taxes

The effects of “hold harmless” have rippled out well beyond the classroom.

Over time, the policy has created a strong correlation between enrollment shifts and property taxes.

Without requisite aid increases tied to enrollment gains, many growing districts have been pushed to raise local taxes at higher and faster rates — a major challenge, especially for the property-poor districts noted above.

The opposite has been true in districts where enrollment has withered. There, state policy has helped them avoid the same extent of local tax increases.

Enrollment has declined by at least 25 percent since 1991 in 96 districts.

Many of these districts are poor, but not all.

Of those that have seen enrollment declines, there are 20 districts where residents earn above average incomes while paying a below average share of that income to property taxes:

They are: South Side Area, Avella Area, Mcguffey, Elk Lake, Bellwood-Antis, Riverside Beaver County, Wattsburg Area, Greenwood, Chartiers-Houston, Trinity Area, Freeport Area,Lake-Lehman, Central Columbia, West Perry, Northern Lebanon, South Butler County, Blue Mountain, Solanco, Neshannock Township, and Abington Heights.

Most state legislative leaders represent poorer, western districts that have lost population and have benefitted financially from hold harmless.

House Majority Leader Dave Reed (R, Indiana) is one.

Like many state lawmakers, Reed believes that the fairest path forward is to allow the new formula to ease inequities gradually.

“More and more money will be put into that formula and help balance the disparity,” he said. “It’s not going to happen overnight. It’s going to take some time, but we got to allow the school districts to adjust as it occurs.”

Advocates for students in districts where needs are high and enrollment has grown push back on this plan, urging state leaders to implement the formula more aggressively.

Reed says that’s a shortsighted view.

“You’ve got a lot of rural, poor districts that would cease to exist without the hold harmless provision for the last 25 years,” said Reed.

One of the loudest voices disagreeing with Reed is POWER, a Philadelphia-area faith-based advocacy organization.

“You should compare the decimation that would happen [in the poor, rural districts] with the decimation that has been going on now for decades in some of these urban districts that have had to do with such underfunding with the great needs that they have,” said David Mosenkis, POWER’s education researcher.

Worthwhile tradeoff?

But here’s where the calculus gets tricky: if lawmakers decide to implement the formula more aggressively, the biggest winners would be the state’s neediest, most burdened districts. For instance, Reading, York, Philadelphia and Erie.

In Reading, at 100 percent formula implementation, the district would receive almost $5,700 more per pupil.

“Oh my goodness, I would probably do a somersault right now,” said Superintendent Mumin, at that prospect.

And overall, this method would actually help a majority of the state’s public school students.

But it’s not just poorer districts that would benefit.

In fact, many wealthier, suburban districts where enrollment has grown would also see a financial boon. And, in effect, this would come at the expense of many poor, shrinking districts.

Of the 63 districts with median household income under $40,000, most would actually do worse with a full implementation of the formula.

Drew Crompton, general counsel to Senate President Pro Tempore Joe Scarnati, a Republican who represents many northwestern districts, says this makes it hard to justify that proposal.

“You could make the argument that the suburban school districts are not getting, quote, ‘what they should be getting’ because of the hold harmless provision,” said Crompton. “But now you want to penalize, if you will, school districts that are losing students at the expense of what I think we could collectively agree are wealthy, suburban school districts that are fast growing.”

Comparison

As an example, let’s compare two districts.

Port Allegany is a tiny school district of 880 students in Mckean County, which is represented by Scarnati. Median household income there is about $37,600, making it one of the 40 poorest school districts in the state.

It’s lost 30 percent of its enrollment since hold harmless was implemented in 1991, meaning that the state still sends it money as if it has 1,262 students.

This year the state sent Port Allegany a basic education allocation of roughly $7.3 million, which works out to about $8,200 per pupil. This is the 16th highest per pupil rate in the state — substantially higher than what most distressed districts receive.

If there were a full implementation of the new fair formula this past year, Port Allegany’s state funding would have taken a significant hit. It would have been cut by more than 40 percent, with its per pupil allocation falling to about $4,780.

“If you’re going to cut, in effect, half of the state subsidy to districts like Port Allegany, they truly would have a very difficult time keeping their doors open,” said Port Allegany superintendent Gary Buchsen. “For us to make that up, we’d basically have to triple taxes.”

Buchsen said that’s not practical or politically palatable based on the population in his district. He also pushed back on the idea of cutting staff or programs — a reality often faced by districts on the losing end of “hold harmless.”

“We don’t want to deny our kids in Port Allegany or in this part of the state the same opportunities that other students have throughout the commonwealth,” he said.

While Port Allegany would be crushed by a full implementation of the formula, South Fayette Township SD would get a significant boost.

That district, in the suburbs of Pittsburgh, has a median household income of $80,804, making it one of the 40 wealthiest districts in the state.

It’s enrollment has grown by 129 percent since 1991. So, although enrollment is now about 2,901, the state has been sending it money as if it still has far fewer students.

This year the state sent South Fayette a basic education allocation of roughly $3.1 million, which works out to about $1,100 per pupil — among the lowest in the state.

With a full implementation of the new fair formula, South Fayette’s state funding would have jumped by about 84 percent, with its per pupil allocation rising to more than $1,900.

Officials in South Fayette did not respond to numerous requests for comment.

Another point to consider is that in South Fayette, residents are spending about 3.7 percent of their income on local property taxes, while in Port Allegany about 0.9 percent of incomes go to property taxes. (The rate in Reading is 1.10 percent.)

These tax figures come from a 2014 study by The Pennsylvania Budget and Policy Center.

Big picture

Are the results in this scenario fair?

Are they worth bearing in order to give the state’s neediest districts major boosts?

Many education advocates reject the very premise.

Instead of taking from one district and giving to another, they say billions in additional investments in state education spending are needed immediately to give all 500 school districts adequate, stable funding.

“The fact is, if we were funding this correctly, there would be very, very few losers,” said Michael Churchill, attorney with the Public Interest Law Center.

Billions of dollars in new investments, of course, would require significant statewide tax increases, similar to those called for by Governor Wolf during his first budget cycle.

Those proposals, like ones calling for a more aggressive implementation of the formula, have failed to garner widespread support.

This in mind, as all districts grapple with sharply rising fixed expenses, such as pensions, many school officials continue to have a bleak outlook for the future.

And as has become the norm in Pennsylvania, the districts tasked with overcoming the greatest hurdles feel the stress most acutely.

But that doesn’t mean there isn’t room for optimism. The fact that the state now actually uses a student-weighted funding formula at all has Reading Superintendent Mumin feeling bullish about his district’s prospects moving forward.

Mumin says they still can’t afford all that they need, but they do have a greater ability to plan and invest for the future.

“That alone, that gets me to do a backflip,” he said. “From a morale standpoint it really has energized my teaching staff and administrators and support staff because they know, ‘Hey, we’re not forgotten. People do recognize what’s going on here. People do recognize that we need help.'”

Data comes from the Pennsylvania Department of Education. Enrollment numbers are based on comparison of 1990-91 and 2014-15 figures, the most up to date. District enrollment includes charter schools, as state funding for charters passes through districts.

Funding data based on the 2016-17 state budget.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.