Horace Pippin: An American Original

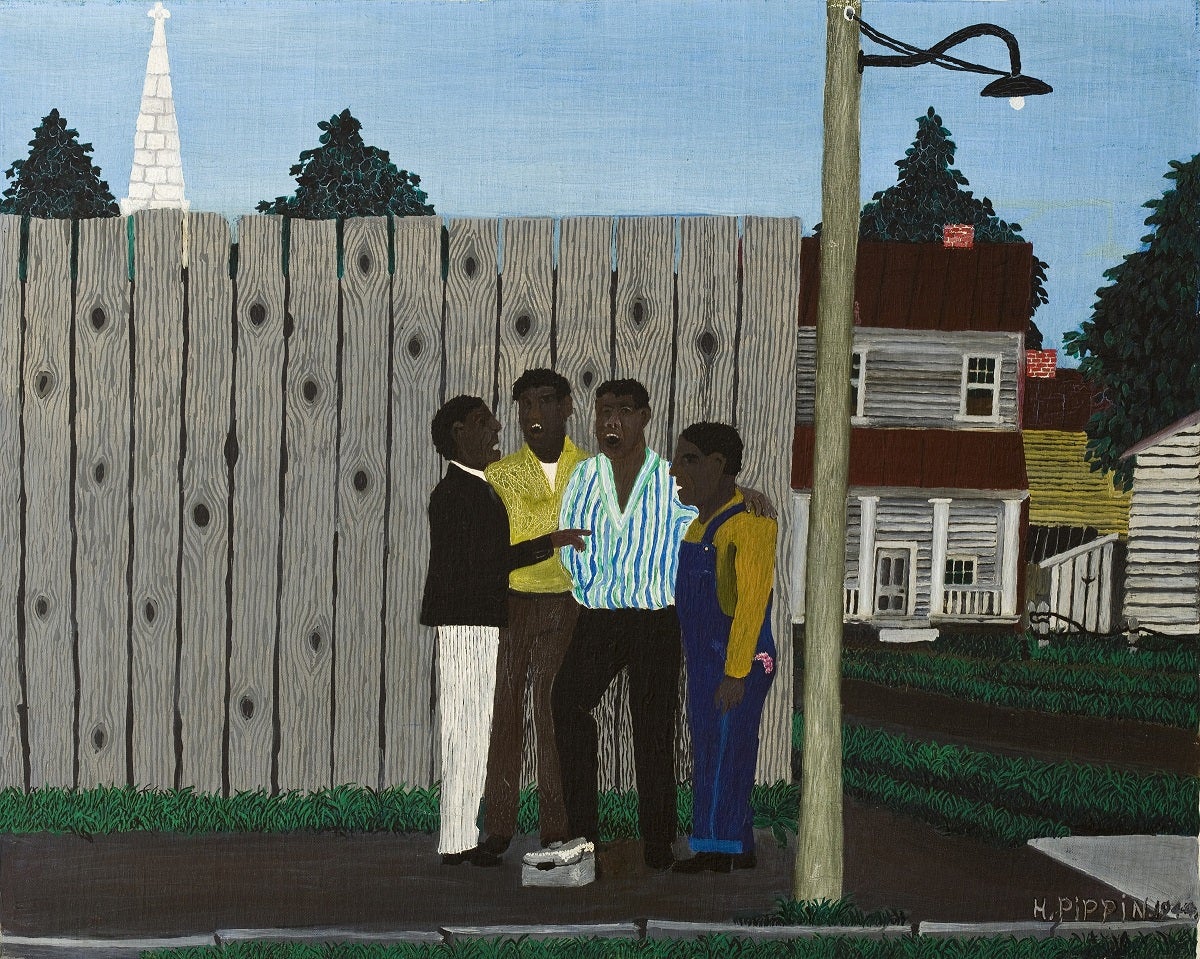

Harmonizing (1944) portrays an African American a cappella quartet singing on a street corner in West Chester, PA.(Photo courtesy of The Brandywine River Museum of Art)

A West Chester native, the renowned artist’s work comes home to The Brandywine River Museum of Art.

Once obscured by a unruly bush, visitors had to hold back the branches to see the gravestone. Today, at the Chestnut Grove Annex Cemetery on the edge of West Chester, a simple stone marker proudly proclaims: “HORACE PIPPIN 1888-1946 PFC CO. K-369TH INF. WORLD WAR.”

Pippin was also one of the leading figures of 20th-century art, known for his insightful, expressive and bold paintings. A self-taught artist, his engaging compositions depict a range of subject material–from intimate family moments and floral still lifes to powerful scenes of his service in World War I to American history as it related to African Americans. He wasn’t discovered until he was nearly 50 years old.

A tall, quiet man, Pippin once famously said: “Pictures just come to my mind. I think my pictures out with my brain and then I tell my heart to go ahead.”

The Brandywine River Museum of Art has assembled the first major exhibition of the artist’s works in this country in more than two decades, “Horace Pippin: The Way I see It.” The landmark exhibition features 65 works from museums across the country and distinguished private collections. It’s on display through July 19.

“Above all, the show suggests, Pippin must have enjoyed painting,” said Audrey Lewis, curator of the exhibition. “His expressiveness, whether it is joy or sorrow really does comes through. Some of the works that resonate the most are those of the humble lives of ordinary black people, just like himself.”

Born in West Chester in 1888, Pippin’s family was one generation removed from slavery. Raised by his mother Harriet, a domestic worker, they moved to Goshen in southern New York state in 1891 where he attended a one-room “colored school.” As a boy, Pippin responded to an art supply company’s advertising contest and won his first set of crayons, a box of watercolors and two brushes.

Dropping out of school at age 15 to support his mother, Pippin worked at a series of menial jobs before joining the Army in 1917 at age 29. A member of the heralded “Harlem Hellfighters,” the all-black 369th Infantry in France, he recorded tragic scenes of the war in notebook drawings. They would become one of the major themes of his work. Just a month before the Armistice, Pippin was wounded in the right shoulder by a sniper’s bullet. He never recovered full use of the arm.

Discharged in 1918 with a steel plate in his shoulder, Pippin returned to the town of his birth and his marriage in 1920, and settled in a house at 327 Gay Street. As therapy to strengthen his injured arm he decorated cigar boxes, then moved on to burning images into wood panels with a hot poker iron.

The artist expanded his talents to oil painting using his left hand to prop up his right forearm and hand which held the brush. His first oil, “The End of the War: Starting Home” (1930-1933) reflects the traumatic wartime experiences the artist would later say “brought out all the art in me.”

“He was teaching himself how to paint coping with his injured arm,” explained Lewis. “It is a muted palette with bursts of red that evokes the sense of desolation amidst the chaos of battle. It’s chaotic, but in a very contained way. The work illustrates his early method of building layer upon layer of pigment so that has an almost sculptural feel to it.”

In 1937 N.C. Wyeth along with art critic and curator Christian Brinton encouraged Pippin to contribute works to a show at the West Chester Community Center, a local black cultural organization. At first amazed that one of his paintings would sell for as much as $150, Pippin was quickly embraced nationally by museums, galleries, art critics and collectors who valued the artist’s self-taught artist’s style– characterized in his time as “primitive” or “folk” art. By 1940, Time and Newsweek wrote about his exhibitions. Patrons ranged from renowned collector Albert Barnes to Hollywood stars such as Claude Rains, John Garfield, Charles Laughton and Edward G. Robinson.

Later in life Pippin explained to celebrated Wilmington artist Ed Loper: “I don’t go around here making up a whole lot of stuff. I paint it exactly the way it is and exactly the way I see it.”

“Harmonizing” (1944) bursts with colors that give his pictures life and warmth. It portrays an African American a cappella quartet singing, shoulder to shoulder, on a street corner in West Chester. Within this townscape, Pippin focuses attention on the singers by contrasting their brilliantly-colored clothing against the stark pattern of the fence, over which a church steeple seems to survey the scene.

In “Country Doctor” Pippin was able to achieve astonishing effects with a limited palette and an intuitive sense of design. He used thin washes of white pigment to convey the heavy snowfall through which a country doctor leads his horse and covered cart, presumably to tend to a patient. Pippin’s painting quietly celebrates the dauntless and gallant country doctor, then an important part of the American rural scene.

“Stylistically, it draws me in with its scrim of slanting snow through which the doctor can be seen leading his horse-drawn carriage along a narrow wooded path, a jagged slash of a small creek running down,” said Lewis. “Like a lot of his work it’s very personal. You can tell that scene had real meaning to him.”

The artist completed two major series with historical themes, one on the life of the abolitionist John Brown, and the other on Abraham Lincoln. “John Brown Going to His Hanging” (1942) is one of Pippin’s most visually and emotionally engaging paintings. Brown is portrayed at the center, sitting atop his coffin while being driven to the gallows. While the crowd looks on, a figure to the far right stares out from the painting, representing Pippin’s mother who legend has it actually witnessed the event.

Like the early blues and jazz artists in American music, Pippin’s art remained rooted in black folk culture, yet also appealed to the wider interests of his day. Less than a decade after he was catapulted to fame, Pippin died of a stroke at his West Chester home on July 6, 1946. Nearly seven decades after his death, this show brings his works to life once more.

Terry Conway is a Delaware Arts and Culture writer. You can view more of his work: www.terryconway.net.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.