HIV drugs stop spread of prostate cancer in mice, Jefferson research shows

Listen Photo via ShutterStock) " title="shutterstock_233620681" width="1" height="1"/>

Photo via ShutterStock) " title="shutterstock_233620681" width="1" height="1"/>

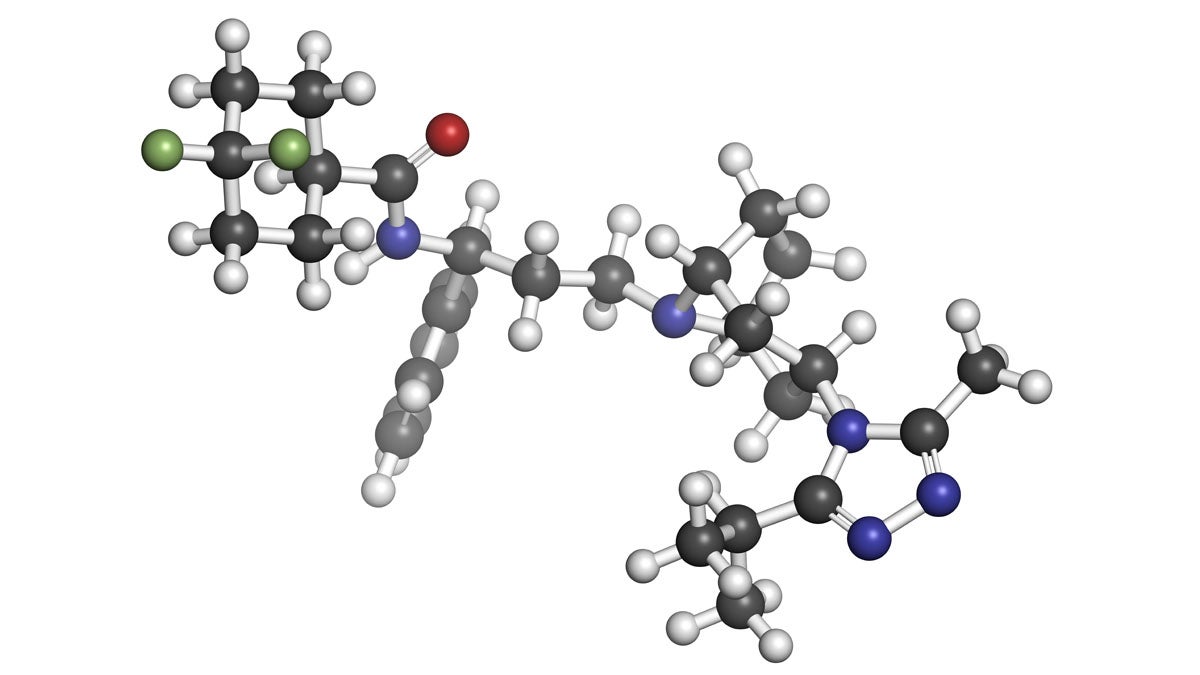

The structure of maraviroc, an HIV drug Jefferson scientists have found works in mice to prevent the spread of prostate cancer.(Photo via ShutterStock)

In most cases, prostate cancer is highly treatable. But once it has started to spread, it can be difficult to stop. New findings from Thomas Jefferson University suggest HIV drugs may be able to keep the cancer at bay.

“If you think of cancer like a car, the approach in the past has been to block the car using chemotherapy or radiation or surgery,” said Richard Pestell, director of Jefferson’s Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center and senior author of the new study. “What we’ve done is we’ve identified the GPS of the car.”

The GPS in this case is the receptor HIV uses to infiltrate cells, known as the CCR5 receptor.

Pestell’s team developed a new mouse model for prostate cancer that spreads to the brain and bone just like it does in people, while keeping the immune system intact. When the team gave the mice drugs to inhibit the receptor, they reduced tumor expansion to the brain by 60 percent and to the bone by 80 percent.

The work, published on Monday in the journal Cancer Research, builds on earlier results from Pestell’s lab that identified similar effects of the CCR5 receptor on breast cancer metastasis.

While scientists aren’t sure why cancerous cells would use the same receptor as a virus to spread, the good news is that HIV drugs already exist to target the molecule.

“Typically it takes a decade to get these sorts of drugs into patients,” said Pestell. “But here the safety’s been approved; it’s been through the FDA.”

Because the drugs are more likely to work in patients with elevated levels of the receptor in their tumors, Pestell said he would like to move into clinical testing on this group of patients as quickly as possible.

Targeted cancer therapies based on individual tumor genetics have been hugely successful before, including Herceptin for breast cancer and Gleevec for certain leukemias. If drugs that block the CCR5 receptor pan out, they would be useful for an even larger number of people.

According to Pestell, approximately 30 percent of men with prostate cancer and women with breast cancer have tumors with abnormally high levels of the receptor.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.