Historical Commission defends role in monastery demolition

Historical Commission chairman Sam Sherman Friday gave a spirited defense of the commission’s role in the recent demolition of a former Francisville monastery.

The monastery, housed in two 19th century brownstone mansions, was once home to the Poor Clares, an order of contemplative nuns. The Francisville Neighborhood Development Corp. tried, and failed, to stop developer 2012 West Girard Associates from tearing down the structures.

An attorney for the developer told PlanPhilly at the time of the demolition that no final decision had been made about what development will replace the monastery.

The buildings were part of the Girard Avenue National Register Historic District, but that listing did not prevent their demolition. They are not on the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places.

Sherman said at the commission’s monthly meeting that he and representatives of the Preservation Alliance met with members of the Francisville neighborhood group more than a year ago. At the time, he said, he suggested that the group ask the commission to add the entire corridor from Girard College to Broad Street to the Philadelphia register ― which would have given the commission power to prevent the monastery’s demolition.

“The full resources” of the commission were made available to the neighborhood, he said, adding that he was “really imploring them” to make a submission. He described these efforts as part of a larger initiative on the part of the commission to be more proactive in advocating conservation issues.

In other news, the commission tried to walk a fine line between respecting a recent precedent it set and economic concerns when dealing with an unusual case regarding the Bourse.

The issue arose when the Department of Licenses and Inspections conducted a review of the building when owner Kaiserman Co. applied for a permit to renovate a large sign on the building’s roof.

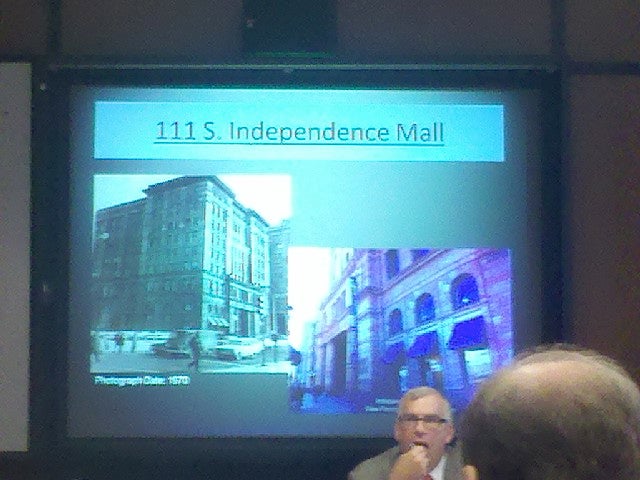

Neither L&I or Kaiserman could find a permit for large cloth advertisements that are attached to the building’s exterior. The Bourse, overlooking Independence Mall, is on the Philadelphia register, and the advertisements are attached to the historic structure by metal brackets ― which isn’t allowed under the code.

The department issued a violation for the advertisements in December, and Kaiserman applied to the commission for a permit to legalize them. The advertisements have been in place since the early 1980s.

Bob Gilbert, Kaiserman’s attorney, was convinced that the structures had been permitted at the time because of the scrutiny given to the firm’s redevelopment of the site at the time and suggested the permits had been lost.

Several commission members, including Sherman, were inclined to agree. He said “it’s surprising, if not unbelievable,” that the advertisements could have been put in without permission.

At the same time, Sherman said, the commission wouldn’t accept the advertisements today because the metal brackets are drilled into the historic structure. He also noted that the commission had recently rejected similar signs on the Lafayette Building, which sits at the corner of 5th and Chestnut streets.

The developer, who is seeking to turn the building into a hotel, argued that the banners would brand the building ― in much the same way that the Bourse’s signs do.

Adding to the complexity of the application was the commission’s desire to keep the Bourse economically viable. Gilbert argued that the advertisements draw in tourists who wouldn’t otherwise know about the building’s food court.

“We hate to see the Bourse go back to what it was,” said commissioner John Mattioni, who agreed with Gilbert’s assessment.

In the end, the commission voted 5-4 to allow the brackets to stay for now ― in part, as architectural historian Robert Thomas said, that approach would prove “least invasive” of the commission’s options.

The permission will only last until the brackets need to be replaced. Kaiserman will then have to come back to the commission for approval to replace them. At that point, Sherman indicated, the commission would like to see the advertisements detached from the building and anchored to the ground in front of the structure ― which isn’t included in the historic designation.

Still, commissioner David Schaff, director of the Planning Commission’s urban design division, argued that it could take years before the brackets needed to be replaced. The commission also debated whether to require Kaiserman to re-apply after the cloth banners ― which last about three years ― need replacing.

The commission also approved the installation of two roof decks on the Parc Rittenhouse, a luxury condo building overlooking Rittenhouse Square. The commission’s architectural committee had asked the architect to design decks that allowed railings to be hidden from street view.

And the commission also recommended to the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission an application by 2200 Park Towne Place for entry on the National Historic Register.

Commissioners said the property, composed of seven towers overlooking the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, is an important example of the history of urban planning ― though not one that commissioners thought was particularly well-thought-out.

“You will not count me as a fan,” Sherman said of the design, which he described as anti-city.

Tenant representative Alan Peckman, a former commissioner, told the board that he was frustrated that owner AIMCO didn’t consult with residents about the entry.

He suspects the company is hoping to use a federal historic designation to apply for tax credits to redevelop the property.

Contact the reporter at acampisi@planphilly.com

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.