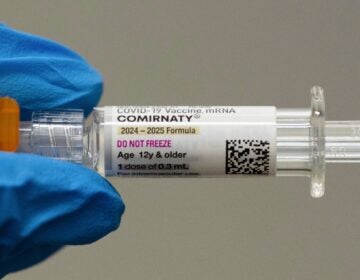

What could CDC changes to hepatitis B vaccines mean for infants and families in Pennsylvania and New Jersey?

A federal advisory panel recommended stopping hepatitis B vaccines in newborns immediately after birth, the standard protocol for more than 30 years.

Listen 1:26

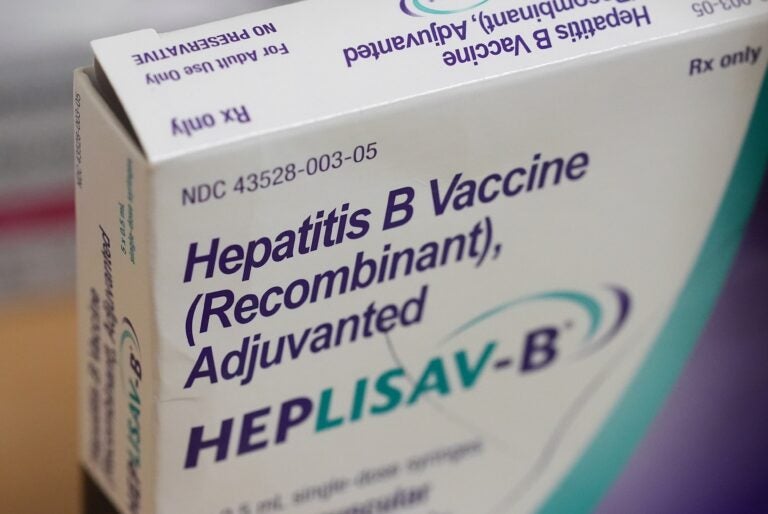

A box of hepatitis B vaccine is displayed at a CVS Pharmacy, Tuesday, Sept. 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

Public health experts are concerned that delaying hepatitis B vaccinations for newborns could increase rates of the infectious disease. Vaccinating newborns for hepatitis B within 24 hours of birth has been a standard practice for more than 30 years in the United States, leading to a dramatic drop in cases among young children.

Now, a federal advisory committee has voted to delay shots in newborns for at least two months, citing disputed and controversial data on safety risks.

If the recommendation is officially adopted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, local health care providers and major medical organizations say the change could upend decades of progress in preventing a highly contagious disease that attacks the liver.

Philadelphia pediatrician Dr. Toni Richards-Rowley said she and others are pushing back and fighting to preserve access to these shots for families who depend on them.

“Parents should know that if they want the hepatitis B birth dose for their child, they can still get it,” she said. “The chips will fall as they may, but we are here for our patients. And regardless of what is being said at a federal level, we at the state and local level will institute what we know is best for our patients.”

Current universal hepatitis B vaccination and proposed federal changes

The hepatitis B virus is highly contagious and most commonly spreads through contact with blood or other bodily fluids during sex, birth or sharing injection drug needles and personal care items like razors and toothbrushes.

About 9 in 10 infants who contract hepatitis B at birth go on to develop a chronic, lifelong form of the disease that has no cure. If left untreated, it can lead to liver damage, cancer and death.

Thousands of children contracted the virus every year during birth before universal hepatitis B vaccination was implemented in 1991, which caused cases to plummet nationally.

The goal of universal vaccination is to catch infants born to mothers who were never screened for hepatitis B or who may have contracted the virus during pregnancy after they were tested at an earlier trimester.

But several members of the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, who were appointed by vaccine critic Robert F. Kennedy Jr., questioned the long-term safety of the shots and existing efficacy data.

They recommended delaying the first shot no earlier than 2 months for infants born to mothers who tested negative for hepatitis B during pregnancy. They also suggested that parents ask for titer testing to confirm the presence of antibodies after just one shot before pursuing the full three-dose series, a strategy not supported by existing scientific data.

How will hepatitis B vaccination change for families?

Major medical organizations like the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Academy of Family Physicians, as well as state health leaders in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, are rejecting these arguments and the proposed changes.

“We will continue to follow evidence-based recommendations that have kept our communities safe for decades,” Acting New Jersey Health Commissioner Jeff Brown said in a statement. “The hepatitis B vaccine has been safely given to millions of newborns and delaying it unnecessarily puts children at risk from an entirely preventable disease.”

In her nearly 30-year career in medicine, Richards-Rowley, who is vice president of the Pennsylvania chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics, said issues or pushback against the hepatitis B vaccine from families were rare until about two years ago.

“Definitely post-COVID, we have been seeing a larger and larger proportion of people saying no to the hepatitis B vaccine,” she said.

Misinformation and disinformation about all kinds of vaccines on social media and from leading government officials like RFK are playing a part, said Richards-Rowley, who added that a majority of families still support and get routine vaccines.

“I wouldn’t give anybody else’s child a vaccine that I wouldn’t give my own child or I wouldn’t take myself,” she said. “If I had any thought, any concern, I wouldn’t give it. But I’ve done the research and I’ve had the education and I know that these are safe.”

For now, access to hepatitis B vaccinations has not changed, Richards-Rowley said.

In Pennsylvania, health insurers are required to cover childhood immunizations recommended by the state Board of Health and trusted medical organizations, regardless of actions at the CDC, under an executive order signed by Gov. Josh Shapiro.

“Insurance companies in Pennsylvania will continue to cover the hepatitis B vaccine for newborns, full stop,” Pennsylvania Insurance Commissioner Michael Humphreys said in a statement.

Pennsylvania has not recorded any cases of hepatitis B in a child under 4 years old since 2019 “due to the high rates of hepatitis B vaccination,” according to state officials.

Most pediatricians and health care workers in hospitals will continue to recommend vaccinations at birth, Richards-Rowley said. It continues to be a critical window for preventing infants who are at risk of infection from developing chronic hepatitis B.

Community health providers may begin to see more families come in with infants that have not gotten their first vaccine dose at the hospital, Richards-Rowley said. In those cases, providers will need to be extra vigilant in examining birth mothers’ health histories and possibly start testing infants for hepatitis B infection.

“Now, does that increase health care costs? Yes. Does that increase anxiety for everybody involved? Yes. Does that increase the amount of time that I can’t spend talking about nursing or jaundice or car seats or other kinds of safety issues? Yeah, it will,” she said. “But are we going to do it? Yes.”

Increasing awareness about hepatitis B and disparities in communities

The moment can also be an opportunity to increase awareness about the disease in general, said Dr. Lin Zhu, assistant professor and researcher at the Center for Asian Health at Temple University’s Lewis Katz School of Medicine.

Although infection rates are generally low in the U.S., cases of chronic hepatitis B are disproportionately represented among Asian, African and Pacific Islander immigrant communities and their descendants.

“They reflect differences in access to vaccines, to care, to public health resources over time, historically and currently,” she said.

Vaccines have become so effective that there is a lack of public awareness about how the virus is transmitted and who is at risk, Zhu said. And because it can be passed sexually, from drug use and by mother to infant, there’s still a lot of stigma attached to the disease.

“When there’s so much stigma associated with a certain disease that a community doesn’t want to talk about it, they feel uncomfortable, and all of that suppresses open discussion. It’s a barrier for awareness campaigns,” she said.

Instead of targeting vaccination efforts, which have helped prevent new cases, Zhu said there’s still a lot of work to do in helping people living with chronic hepatitis B who face significant barriers to treatment like insurance gaps, financial strains, lack of transportation and limited access to “culturally or linguistically competent care.”

An estimated 640,000 adults in the U.S. live with the lifelong disease, federal data show.

“Whether we’re talking about screening, vaccines or linkage to care for people with chronic infection, I think it needs to be a joint effort from communities, from health care systems, different stakeholders,” Zhu said. “To really effectively address these barriers, different parties need to work together.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.