Health by zip code? Some Philly neighborhoods are ‘primary care deserts’

A report released Tuesday focused on several shortage areas in primary care access for Philadelphians.

Listen 2:06

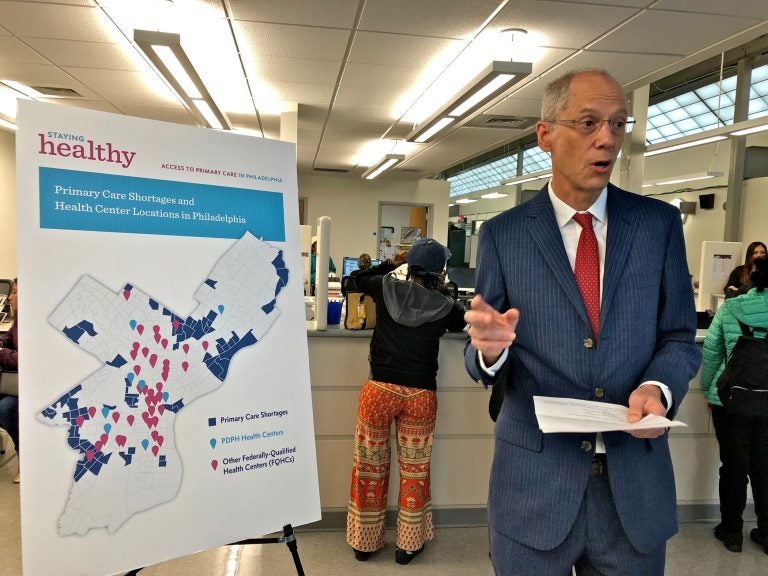

Philadelphia Health Commissioner Tom Farley uses a map to illustrate primary care shortages in neighborhoods in the city's Northeast and Southwest. (Nina Feldman/WHYY)

This article originally appeared on PlanPhilly.

—

It was a busy morning at Health Center 10 on Cottman Avenue in Northeast Philadelphia. The seating area was full of families waiting to be called in by a doctor, and a line to see the receptionist snaked throughout the clinic.

If the place had the feeling of bursting at the seams, it’s because it is — Health Center 10 is by far the busiest of the eight primary care health centers run by the Philadelphia Department of Public Health. It sees 67,000 patient visits a year, and new patients add their names to a long waiting list for appointments. City clinics treat patients regardless of insurance status — making them the only option for many families. On Tuesday, the sound of a construction crew hammering away in the basement reverberated through the building — an effort to expand the number of exam rooms spaces.

Health Center 10 is the only Health Center operated by the city in the Northeast, and according to a report released on Tuesday by Philadelphia Health Commissioner Thomas Farley, that scarcity has a cost. Areas of the Northeast, along with Southwest Philadelphia, have much lower access to primary care providers than elsewhere in the city. Primary care, while often overlooked, can be critical in keeping people healthy.

“When people think of our health system, they mainly think of hospitals where you go when you get really sick,” said Farley. “But a primary care clinics are where doctors and nurses prevent people from getting really sick in the first place.”

Not only does primary care help with better health outcomes, it lowers costs. Health care for people who rely on emergency departments is more expensive than for people who see primary care doctors regularly for check-ups.

The report released by the city on Tuesday in partnership with the Leonard David Institute of Health Economics at the University of Pennsylvania focused on several shortage areas in primary care access for Philadelphians.

The first is supply. While the city as a whole offers fairly good access — just over 1,200 residents per provider — some areas like the Northeast have more than 3,500 residents per primary care doctor, which qualifies them as primary care deserts.

The second shortage is insurance. The percentage of uninsured Philadelphians has decreased since the Affordable Care Act went into effect and Pennsylvania expanded Medicaid in 2015 — there are now only about 12 percent of adults in Philadelphia who don’t have insurance, down from 20 before the state’s Medicaid expansion. But the proportion of providers that accept Medicaid has actually gone down — traditionally, reimbursement rates are lower for Medicaid than for private insurance and Medicare.

“It does no good to give a person insurance and then not have a provider that can take their insurance,” said Dr. Raynard Washington, Chief Epidemiologist at the Philadelphia Health Department. Washington also pointed out that the small group of uninsured, which is disproportionately black and Latino, overlaps substantially with the geographic areas that have a shortage of primary care providers.

Health Center 10 offers a picture of both the strengths and weaknesses of the city’s primary care offerings. Many patients use the clinic as their regular primary care provider.

One of those people is Anthony Smith, 62, who lives nearby and said he has been visiting Health Center 10 roughly every three months for the past 15 years for regular check-ups. He has private insurance but said he wouldn’t consider going anywhere else, because the quality is good at the clinic. He said he doesn’t mind the wait times and imagines they’d be just as long anyplace else.

Orlando Garcia, 72, is originally from Colombia but has lived in the neighborhood for many years. As he waited for his wife to finish up her appointment, and said he loved going there for the consistent quality of the doctors, nurses and Spanish interpreters.

“Not just a few of them, but every single one,” he said in Spanish.

He didn’t want to say whether or not he had insurance but made it clear he was grateful he and his family had never been turned away.

Still, this facility is just one clinic.

Health Commissioner Farley said he knows that a few more exam rooms in the basement aren’t going to solve the shortage crisis. He is working with City Councilman Bobby Henon to secure a facility to build a new health center in the area, which, he said, the city does have some funding set aside for.

Ultimately though, Farley said it’s up to the private sector to respond to the results of the study and offer quality primary care where it’s needed most.

“This is a city that has some of the best medical centers in the country,” he said.

“Now we are calling on other health systems and Federally Qualified Health Centers to do their part as well.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.