Haitian art brings attention to child slavery

At 27, Edens Cathyl might seem like an internationally successful artist. His black-and-white drawings, on view at Stuart Country Day School’s Considine Gallery through Feb. 12, depict life in rural Haiti. We see beautifully executed scenes of a bay, a mermaid blowing a horn, a baby goat nursing, climbing trees for coconuts and planting a field, walking animals. A woman carries a basket of fruit on her head and a big fish swims in the sea.

But Cathyl’s life in Haiti is anything but paradisiacal. Born into extreme poverty, his mother gave him up as an indentured servant, a practice not uncommon in Haiti.

“In a country as poor as Haiti, when we say not everyone in a family can eat everyday it isn’t an exaggeration,” said Ellen LeBow, an artist who lives in Massachusetts but has helped Cathyl learn art skills and sell his work. “Some parents feel they have to give one or more of their children to someone else, either a family member or a friend of a friend who promises to feed, clothe and educate the child in return for some work duties. The children are often beaten, starved, over-worked and raped. Everyone knows it, everyone denies it. The word for such a child is restavek — meaning ‘rest’ or ‘stay with.’ But no one admits they have a restavek in their house.”

Edens’ mother sent him to her brother, a man with three sons. The uncle beat Edens, said LeBow, but he did send him to school.

LeBow taught Cathyl to use the technique in which he found his voice: India ink is brushed onto the surface of a hard board that is coated with soft white kaolin clay (gesso board). Cathyl draws into the ink with a blade, carving to reveal the white beneath it.

Cathyl has a sister and two younger brothers, but LeBow says they were not restaveks. Edens’ father was history by the time he was born. Cathyl was helped by the Matenwa Community Learning Center started by Christine Low, an American educator working with restaveks, and Abner Saveur, a teacher from Matenwa and a former restavek. LeBow was brought on 16 years ago to develop the art program. Cathyl was 11 when LeBow first met him.

“Edens has an uncanny natural gift for detailed drawing, subject matter and composition but does not automatically make art,” said LeBow. “In a place like Matenwa general life needs trump art-making. Also, for the kind of art Edens does best I have to bring him the materials. People don’t have paper or paint or pencils in their homes so if he runs out he has to wait for more. I encourage him because he has a talent others don’t.

“Edens loved school, was top in his class and with only a little help taught himself English,” continues LeBow. “At 13 he was impossibly thin for his elongating frame, with enormous eyes and skin as dry and grey from malnutrition as an old man’s. He became excellent in silver cutting, not afraid to try new things and it soon became clear he could draw better than anyone else at the art center.”

When he was 18 Cathyl moved into the art center where he still lives. Even with help and encouragement, life continues to present challenges for Cathyl, who bought a motorcycle to use as a taxi. He has been trained as a cement mason but there is little work, and he has recently become a father.

Princeton-based artist and curator Madelaine Shellaby discovered Art Matenwa, Ellen LeBow and Edens Cathyl through her own interest in Haiti. In 2011, Shellaby, along with Stuart colleague Anne Hoppenot, founded Konekte Princeton Haiti to improve the lives of children and their communities through educational Initiatives.

“In order to provide a good education, there needs to be an incentive for the teachers,” says Shellaby. “We help raise the money for their salaries and provide books and art supplies.”

The scenes depicted by Cathyl are imbued with symbols of voodoo. Voodoo originated in the Caribbean when African slaves were forced to convert to Christianity. Practitioners of Voodoo participate in rituals that serve spirits called loa. Every loa has a unique veve, or visual symbol.

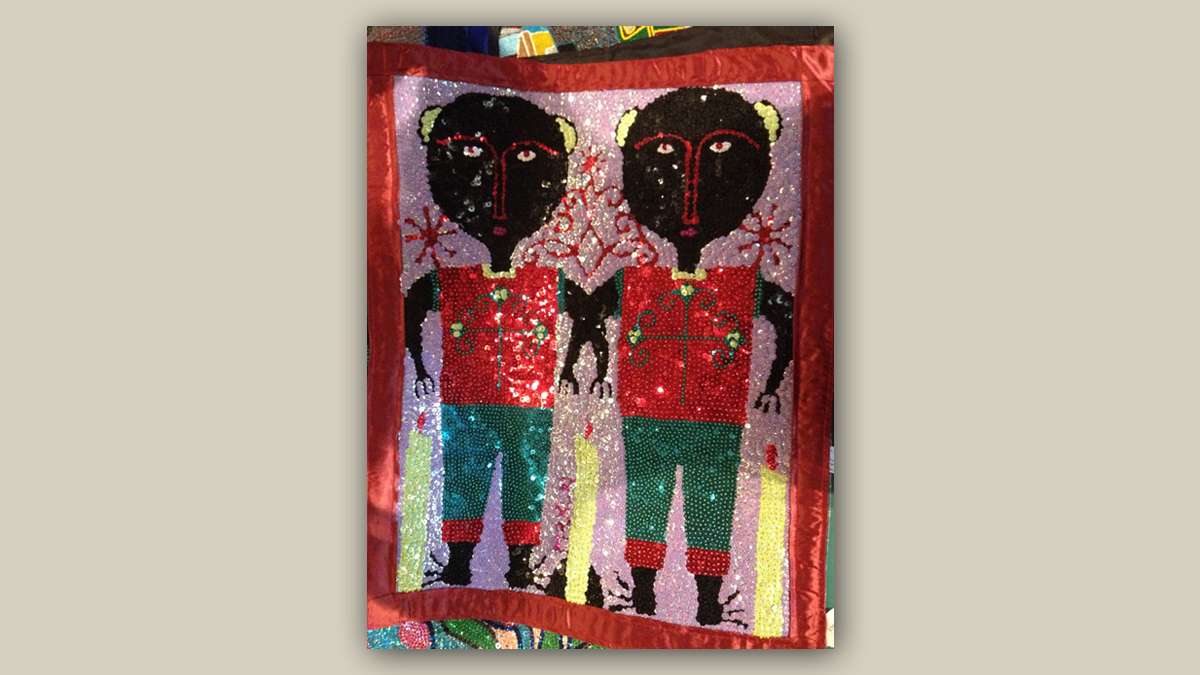

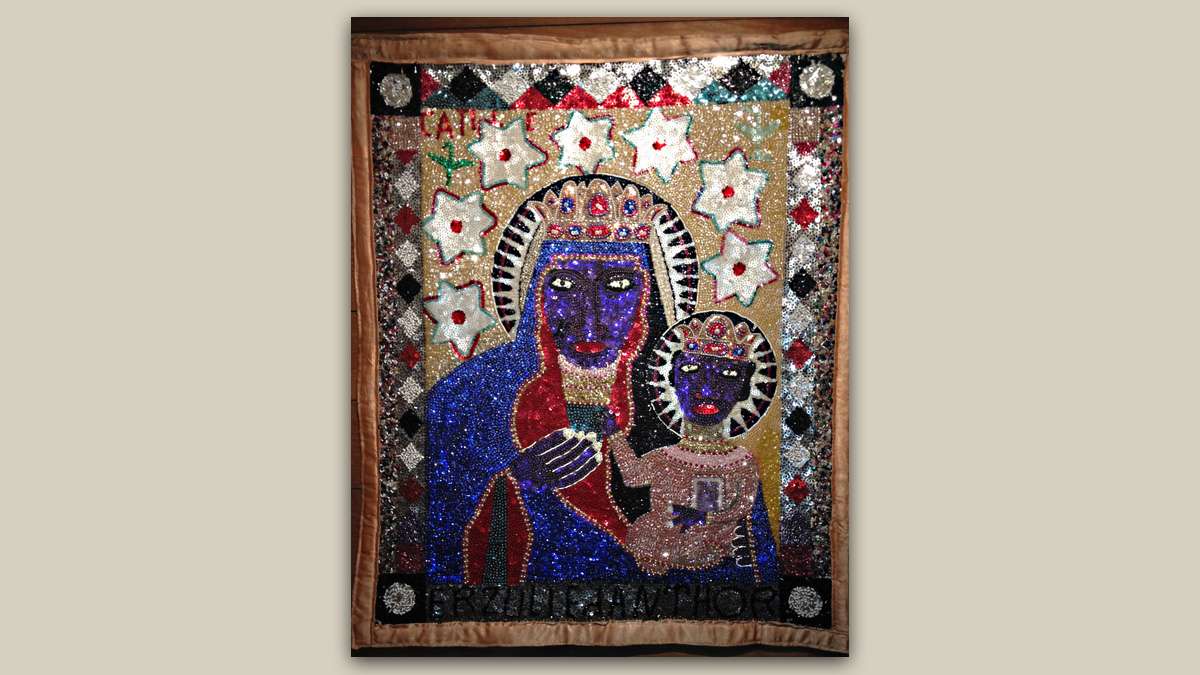

Also on view, alongside Cathyl’s work, are sequined-covered Haitian flags. These are created as sacred ritual objects within the Vodoo community, welcoming the pantheon of spirits to temple ceremonies. Flags most often commemorate specific spirits or saints – combining Christianity with the original spirits of the Kongo — but since 2010 the catastrophic earthquake has become a common subject.

Haitian Art – Edens Cathyl: Stories from Haiti, and Haitian Flags: from the collections of Jill Kearney and Indigo Arts is on view at the Considine Gallery, Stuart Country Day School of the Sacred Heart, 1200 Stuart Road, Princeton, through Feb. 12. Opening reception is Friday, Jan. 23, 5 to 7 p.m., with an artist talk on Tuesday, Jan. 27, 11 a.m. Jan. 25, 5-8 p.m., fundraiser for Konekte Princeton Haiti. $60 ticket, includes Haitian food from Mommy Joe’s in Trenton. Money raised will go toward teacher salaries in Fond Parisien.

___________________________________________

The Artful Blogger is written by Ilene Dube and offers a look inside the art world of the greater Princeton area. Ilene Dube is an award-winning arts writer and editor, as well as an artist, curator and activist for the arts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.