Grand jury declines to indict woman in Emmett Till killing

Leflore County DA Richardson says the grand jury determined that there was insufficient evidence to indict Carolyn Bryant Donham on charges of kidnapping or manslaughter.

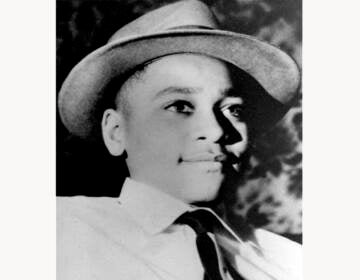

In this 1955 file photo, Carolyn Bryant poses for a photo. A grand jury in Mississippi has declined to indict the white woman, Carolyn Donham, known as Carolyn Bryant, whose accusation set off the lynching of Black teenager Emmett Till nearly 70 years ago, despite revelations about an unserved arrest warrant and a newly revealed memoir by the woman, a prosecutor said Tuesday, Aug. 9, 2022.(AP Photo/Gene Herrick, File)

A grand jury in Mississippi has declined to indict the white woman whose accusation set off the lynching of Black teenager Emmett Till nearly 70 years ago, despite revelations about an unserved arrest warrant and an unpublished memoir by the woman, a prosecutor said Tuesday.

After hearing more than seven hours of testimony from investigators and witnesses, a Leflore County grand jury last week determined there was insufficient evidence to indict Carolyn Bryant Donham on charges of kidnapping and manslaughter, Leflore County District Attorney Dewayne Richardson said in a news release.

It is now increasingly unlikely that Donham, who is now in her 80s, will ever be prosecuted for her role in the events that led to Till’s lynching.

The Rev. Wheeler Parker, Jr., Emmett Till’s cousin and the last living witness to Till’s 1955 abduction, said Tuesday’s announcement is “unfortunate, but predictable.”

“The prosecutor tried his best, and we appreciate his efforts, but he alone cannot undo hundreds of years of anti-Black systems that guaranteed those who killed Emmett Till would go unpunished, to this day,” Parker said in a statement.

“The fact remains that the people who abducted, tortured, and murdered Emmett did so in plain sight, and our American justice system was and continues to be set up in such a way that they could not be brought to justice for their heinous crimes.”

An email and voicemail seeking comment from Donham’s son Tom Bryant weren’t immediately returned Tuesday.

In June, a group searching the basement of the Leflore County Courthouse discovered the unserved arrest warrant charging Donham, then-husband Roy Bryant and brother-in-law J.W. Milam in Till’s abduction in 1955. While the men were arrested and acquitted on murder charges in Till’s subsequent slaying, Donham, 21 at the time, was never taken into custody.

The men later confessed to the crime in a 1956 magazine interview but weren’t retried. Both are now dead.

In an unpublished memoir obtained last month by The Associated Press, Donham said she was unaware of what would happen to the 14-year-old Till, who lived in Chicago and was visiting relatives in Mississippi when he was abducted, killed and tossed in a river. She accused him of making lewd comments and grabbing her while she worked alone at a family store in Money, Mississippi.

Donham said in the manuscript that the men brought Till to her in the middle of the night for identification but that she tried to help the youth by denying it was him. Despite being abducted at gunpoint from a family home by Roy Bryant and Milam, Till identified himself to the men, she claimed.

Till’s battered, disfigured body was found days later in a river, where it was weighted down with a heavy metal fan. The decision by his mother, Mamie Till Mobley, to open Till’s casket for his funeral in Chicago demonstrated the horror of what had happened and added fuel to the civil rights movement.

The Justice Department in 2004 opened an investigation of Till’s killing after it received inquiries about whether charges could be brought against anyone still living. Officials said the statute of limitations had run out on any potential federal crime, but the FBI worked with state investigators to determine if state charges could be brought. In February 2007, a Mississippi grand jury declined to indict anyone, and the Justice Department announced it was closing the case.

The department then reopened its investigation after a 2017 book by historian Timothy Tyson quoted Donham as saying she lied when she claimed that Till grabbed her, whistled and made sexual advances toward her. Relatives have publicly denied that Donham recanted her allegations about Till. But federal officials announced last year that they were once again closing their investigation, saying there was “insufficient evidence to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that she lied to the FBI.”

In an email to The Associated Press on Tuesday, Tyson said the warrant that was uncovered in June revealed that local law enforcement in 1955 assumed that she was involved in Till’s killing. But the warrant “did not appreciably change the concrete evidence against her,” he wrote.

“Moral culpability and legal guilt are not always the same thing,” Tyson wrote. “The most important thing that the Emmett Till case can do is to compel all Americans to examine our country’s racial disparities in wealth, opportunity, health care, criminal justice, education, and virtually every other measure of well-being and access to the full bounty of American life.”

___

Associated Press Writer Allen G. Breed contributed to this report.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.