Getting ready for Charlie’s Law on safe disposal of unused medications

Pharmacists and doctors required to assist in safe disposal and to educate patients on dangers of holding on to medicines

(sandramatic/BigStock)

This story originally appeared on NJ Spotlight.

Those unused painkillers, antibiotics and other medicines lurking in your bathroom cabinet: It’s time to hand them back to the pharmacist or neutralize them with a special kit, but don’t leave them lying around, and don’t flush them down the toilet.

That’s the message from a new state law that requires pharmacists and doctors to educate patients about the dangers of holding on to medicines after treatment ends, and to encourage their safe disposal.

Charlie’s Law, signed by Gov. Phil Murphy on Jan. 21 after a year-long journey through the Legislature, is named after a 33-year-old man who died after taking left-over opioids, highlighting the risks of having that class of painkillers available to someone without a prescription.

The law, which will become effective in May, directs health care professionals to give written information about unused drugs and needles to their patients when there is a risk that they can be “stolen, diverted, abused, misused or accidentally ingested,” risking the health and safety of a patient and his or her household.

The requirement also applies to drugs that can harm the environment when disposed of in household trash or flushed down the drain, or those that may be stolen from the trash before they are “deactivated.”

Rendering the drugs harmless

And the law requires pharmacists and doctors to provide their patients with products that can render the drugs harmless, at a cost to patients or free of charge.

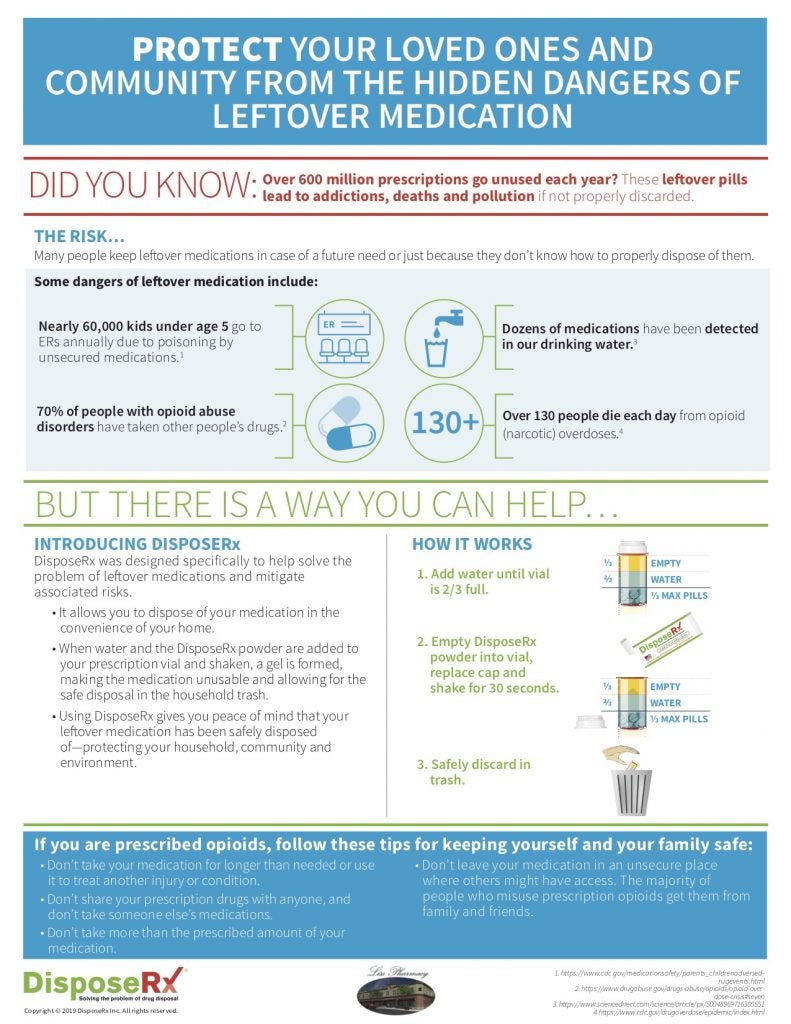

One such product, offered by DisposeRx, a North Carolina company, deactivates medication by mixing it with a polymer powder and water, creating a gel that is then safe to throw in the trash, said William Simpson, president of the company, which is working with about 1,600 New Jersey pharmacies to distribute its product.

“The patient would take our powder, put it in a medicine vial, add water, shake it up, and in 10-30 seconds it creates a gel, something between a syrup and a rubber cement, and that is then safely disposed of in their household waste,” Simpson said in an interview.

DisposeRx, one of a number of companies providing similar products to pharmacies across the country, is working with Garden State Pharmacy Owners (GSPO), an association of independent New Jersey pharmacies, to help its members comply with the new law.

At Liss Pharmacy, a GSPO member with two stores in Newark, pharmacist-in-charge Rich Mistichelli said in mid-February that he has been trying for about the last month to educate his customers on the need to safely dispose of their medications.

Reluctant to let go of old medications

They haven’t yet clearly shown that they are willing to act on his recommendations, however. “I think they are intrigued; they are listening. I don’t know if they’re receptive yet, but I think they are understanding. In the past, they were either keeping them or flushing them down the toilet,” he said.

Still, many customers, particularly the elderly, have trouble accepting that they shouldn’t hold on to medications just in case they need them in future.

“It’s a very hard for patients to grasp the concept that they need to dispose of unused or unwanted or never-finished medication, and they usually just stockpile it,” he said.

Shifting that mindset will require all dispensers of medicine to send the same message, he said. “For this new law to become successful, everybody’s got to be on the same page: doctors, pharmacists, insurers.”

As an alternative to using a product like that offered by DisposeRX, patients can turn in their unused medications to “vaults” provided by some pharmacies, police stations, or the federal Drug Enforcement Administration, Mistichelli said.

Where unsecured medications can end up

In January, he started giving his patients a flyer that says some 130 people a day across the United States die from opioid overdoses; that 60,000 children under five years old are taken to emergency rooms every year because they have taken unsecured medications, and that “dozens” of medications have been found in drinking water.

But such hazards can be avoided by using the DisposeRx product, the flyer says.

Every unit of the DisposeRx product costs Mistichelli $1.50 for a one-time use, and it’s a cost he is prepared to absorb, at least for now, in the hope of changing his customers’ behavior.

If customers face a charge to dispose of their unused medicines, many are likely to revert to their old habits of simply throwing them in the trash or the toilet, he said.

State Sen. Robert Singer (R, Monmouth and Ocean), the prime sponsor of Charlie’s Law, said the bill was motivated by the fact that there was no requirement on pharmacies or doctors to instruct their patients on the safe disposal of medications, and nothing to say that patients should dispose of medicines if they are not being used.

“The overdose situation affects more and more families,” he said. “The more we talk about what these drugs do to young people and families, and how it’s killing people, people will start to listen. We can’t make them, but I think we have to provide the tools to educate them.”

But even if advocates persuade medication users to change their behavior, it’s less clear that the new law will result in fewer pharmaceuticals finding their way into public water systems, said Amy Goldsmith, New Jersey state director for the environmental group Clean Water Action.

She argued that most of the water-borne medications come from human waste, and that issue is not addressed by the new law.

“It’s really good that we’re collecting this stuff and trying to make it inert,” she said. “But will it make the biggest difference? Probably not.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.