Germantown’s ‘Sign Wars’ continue amid zoning-code uncertainty

“You know that sign is illegal, sir,” the man shouted as he pulled his large cream-colored pickup truck close to the curb. He grinned at Jeff Smith, who is teetering on a stepladder and pulling out a pocketknife. The men banter. The men share a laugh.

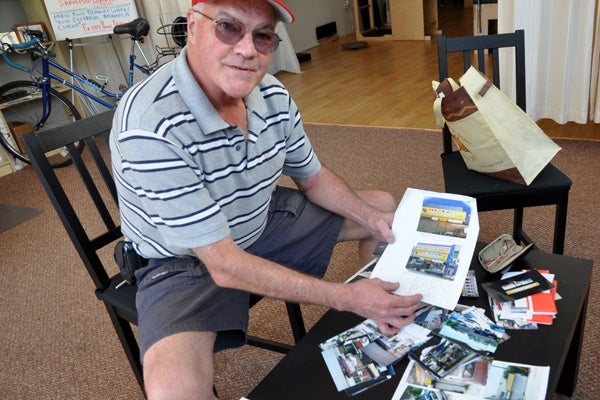

Smith is pushing 70 years old. He’s wearing a red baseball cap, khaki shorts and tall white socks with loafers. As the truck drove away, he began to attack the plastic signs affixed to corner utility pole. He ripped the “we buy houses” sign into two pieces with glee.

“He used to hate me,” Smith said of his surprise visitor, who doesn’t seem to hate him anymore.

As he climbed down the ladder, Smith said his vigilante-style sign-control activities have gotten him in the type of trouble that accompanies perceptions of racism, which is what some Germantown business owners thought guided Smith.

“I’m not racist at all,” he countered. He just cares about having some business-district order and continuity.

Before the Chelten Avenue zoning overlay took hold, Smith said business owners went overboard putting whatever they wanted in the windows, including neon signs and flashing signs.

“There was a lot of graffiti on the facades, and it started to look really bad,” he recalled.

A long-time resident and local business owner, Smith removes those illegal signs to protect a slice of Germantown history. He once raised more than $2,500 to cover court costs in a battle to force L&I and the City to enforce sign laws.

So, to answer the man in the pickup’s question: Yes, he knows those signs are illegal.

Signs Matter

At first glance, Smith’s obsession with sign controls may seem like a picayune issue, but a recent research study of outdoor advertisements held that they do impact a neighborhood’s quality of life.

Amy Hillier, assistant professor in city and regional planning at the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Design, co-authored a study that counted and categorized advertisements in a few Philadelphia neighborhoods. Colleagues did the same in Los Angeles, New York and Austin, Texas.

Germantown was deemed too economically and racially diverse to be included in a study that looked at signage in East Falls and West Mt. Airy.

Researchers found the most common outdoor ad was for cigarettes, attributed to the fact that many neighborhood stores had multiple signs. In general, poor neighborhoods had a wealth of advertisements for fast food, entertainment and cars; Hillier posited those signs promote sedentary behavior and obesity.

“They know exactly what they are doing,” she says of advertisers. “Corporate America is really abusing us. … Our city doesn’t enforce sign codes at all. There is absolutely a correlation to health, it’s not just about aesthetics or blight.”

How It Applies To Germantown

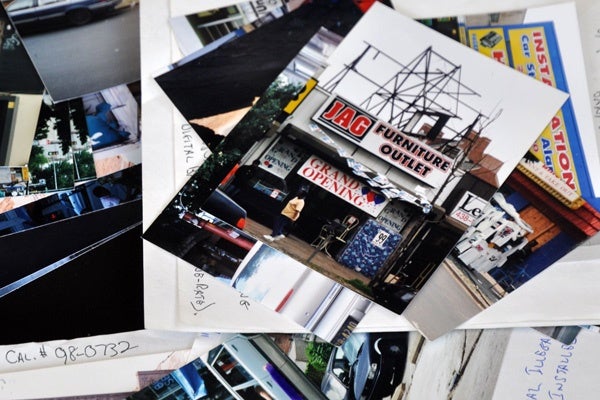

Smith has waged his sign war more than a decade, but he’s not exactly admired for it. A local business owner once called him a Nazi, in fact, for taking the company to court for refusing to take down their “excessive” business signs and blaring music at the store entrance.

The signs for Hi Tec, a West Chelten Avenue electronics store, totaled over 300 square feet. The zoning overlay limits it to 40 square feet.

“This is just flat-out lousy looking and crass,” he said, poring over storefront photographs taken through the years.

Applying for signs is an over-the-counter transaction at L&I. Matt Wysong, the city Planning Commission’s Northwest Philadelphia community planner, said sign permits are rarely challenged, let alone taken through the court system.

“If it does comply [with the overlay] they issue it over the table,” Wysong said. “If not, it goes to the Zoning Board.”

Smith – along with West Central Germantown Neighbors and Penn Knox neighbors – took the Hi Tec case all the way to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. After the Supreme Court ruled in Smith’s favor, L&I posted a cease-and-desist order. Within a day, the signs were gone. Within weeks, so was the store.

“I was not popular,” he said of a battle that the Society Created to Reduce Urban Blight (SCRUB) continues to fight to this day with its “Bandit Project” aimed at the light-pole signs Smith so gleefully slices.

“I think it’s a resource issue,” said SCRUB staff attorney Stephanie Kindt. “L&I has no department for sign control.”

When Is It Taken Too Far?

While Smith served as Germantown Business Association president in early 2000, the neighborhood group Central Germantown Council accused him as being too “punitive”.

“If you’re a business association, you’re supposed to be encouraging them,” he conceded, maintaining his intentions was to help Germantown, not to become a bounty hunter.

Today, Smith still tries to enforce the special sign controls but compromises with local businesses. In fact, he claims friendly relationships with business owners who once didn’t understand his motives.

Recently, he asked a store manager to take down an illegal sign politely, and they did. In another case, a car rental company wanted a 25-foot tall sign to dangle from an existing pylon. Smith says he convinced them it wasn’t necessary, no court intervention necessary.

By this time next year, however, it’s possible that Smith’s leverage will disappear. The zoning code is being overhauled with sign controls on the chopping block. While the City Council hashes out the new zoning code, any decisions about sign overlays have been postponed until community meetings are scheduled.

Zoning Code Commission Executive Director Eva Gladstein said meetings with Northwest Philadelphia residents about sign-control changes won’t occur until next year.

For his part, Smith plans to lobby to keep controls in place.

“I’m proud of what I’ve done,” he said. Of excessive signage about which he regularly calls L&I, he added, “It doesn’t have to happen. You don’t have to take a historic part of the city like that and degrade it.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.