Genetic test helps explain why anti-depressants work only for some

Listen 4:48Choosing a medication to treat mental illness can be a gamble. Some patients don’t respond at all. Others see marked improvement.

Many patients find they need to experiment for a long time to fine tune a complicated cocktail of pills.

What accounts for these erratic drug responses? Psychiatry is not entirely sure.

Genomind, a Bucks County company, is trying to crack the code through genetic testing.

Take chronic depression, one of the most common mental illnesses. Half of patients don’t respond to the most often prescribed medications. Half. Many of them continue to try pill after pill.

Virginia von Rhine of North Port Norris, in Cumberland County, N.J., lived through that drill.

“Prozac, Paxil, you name it, I have been on it,” she said. “Cocktails and mixtures of this, that and the other thing.”

von Rhine has struggled with depression and anxiety most of her life. With every new prescription, she hoped the darkness would lift:

“You wait, you wait, you wait, and I do a lot of crying, cry, cry cry, and I lie on the couch, and I sleep.”

No psychiatrist or therapist could shed light on why nothing worked for von Rhine.

That’s nothing unusual, says psychiatrist Jay Lombard, chief scientific officer for Genomind, a biotech firm based in Chalfont.

“I feel like we do operate in the dark,” Lombard said.

But he’s determined to generate more light. He says the same complicated mechanisms that create mental illness can offer clues to how people will react to medications:

“Clearly, genetic and biological factors are critically important to improve predictability of what type of treatment should be applied for particular types of patients to improve their response rates.”

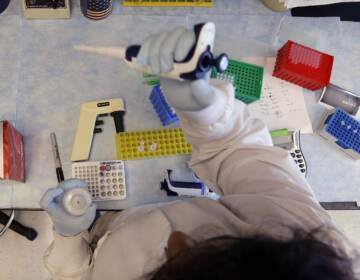

Genomind, in essence, uses a patient’s spit to see inside her brain.

In a test marketed by Genomind, DNA is extracted from the patient’s saliva.

“There is an analytical process looking at the raw data of the genes that are involved in psychiatric clinical medicine,” Lombard said.

Ten genes are analyzed in the test.

Some are genes related to metabolism, explains Dr. Rachel Dicker, director of clinical sciences at Genomind.

“Someone might have a gene which makes it more likely that they would slowly break down medications,” Dicker said. “So they would be more predisposed to having side-effects and toxicity, and that would be important for the clinician to know, to think about how they would want to dose a medication.”

Modern anti-depressants work by increasing seratonin levels in the brain. So the Genomind analysis looks at whether a patient is genetically ill-equipped to respond to so-called “SSRI’s” – selective seratonin reuptake inhibitors. Prozac is one example of an SSRI.

Genomind found this trait in Virginia von Rhine. It’s why many common medications didn’t work for her.

“It was both a relief and a sadness,” she recalled. “You know, it’s like, ugh, there’s nothing I can do, but on the other hand it’s like: Wow, I am not crazy. I’m right. I knew there was something wrong, and nobody understood!”

Jay Lombard says the relief von Rhine expressed is not uncommon:

“When a patient is able to see that a biological process is driving an underlying psychiatric disorder, there is really, truly a transformational process that occurs in the patient’s mind,” he said. “The realize it’s not their fault if they have had treatment failures. They also are less likely to give up hope on the field of psychiatry. It empowers the patient.”

The test developed by Genomind is covered by many insurance companies. Paid out of pocket, it costs $750.

Tests like this one are helpful, says Falk Lohoff at the University of Pennsylvania. But, they are not the be all and end all.”

“These genetic tests are tools,” Lohoff said. “They can help us; they will give us more information, but they are by no means deterministic, that if you have a certain marker that you are untreatable.”

Lohoff conducts research in this same field – identifying genetic markers that predict better treatment response. He says the Genomind test is a step in the right direction, but doesn’t cover enough ground.

“We’re looking at 10 genes only,” he said, “and the human genome is much more complicated than 10 genes, and probably, many more genes are involved in drug response in general, so that this is a very smallportion of the variance that is captured by this test, and really what’s needed is more clinical testing.”

Genomind’s Lombard gets a little exasperated by the chorus of caution around genetic testing:

“‘Show me more data, show me more data, show me more data,'” he imitated the critics. “And in the meantime, what happens is that patients suffer through not being able to translate what we know on the bench side,to the bedside.”

Virginia von Rhine says the test developed by Genomind changed her life.

As a result, her therapist has come up with a new course of treatment that involves stimulants.

This, she said, has taught her something she never knew before: What it’s like “to want to do things, like get out of bed.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.