Generations of Alexander Calder art a trinity of blessings for Philadelphia

-

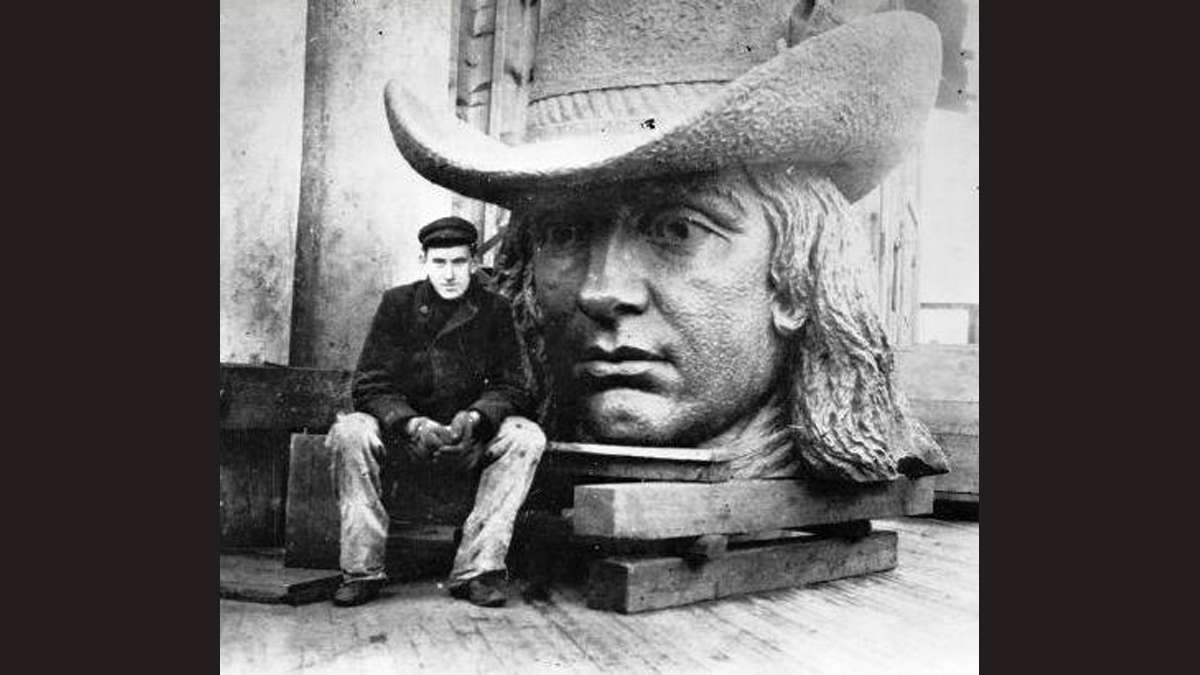

Alexander Milne Calder is shown with the head of his statue of William Penn, now atop Philadelphia City Hall. Calder won a competition to make 'William Penn' in 1874 and completed all his City Hall work by 1893. (Wikimedia Commons)

-

The Swann Memorial Fountain was named for Dr. Wilson Cary Swann, the founder and president of the Philadelphia Fountain Society, which provided fresh drinking water throughout the city. The three reclining figures represent Philadelphia's three main waterways: the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers and Wissahickon Creek. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

This memorial to Shakespeare in front of the Central Branch of the Philadelphia Free Library comprises two figures that represent tragedy and comedy: Hamlet, leaning his head against a knife; and King Lear's jester, Touchstone, with his head thrown back in laughter. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

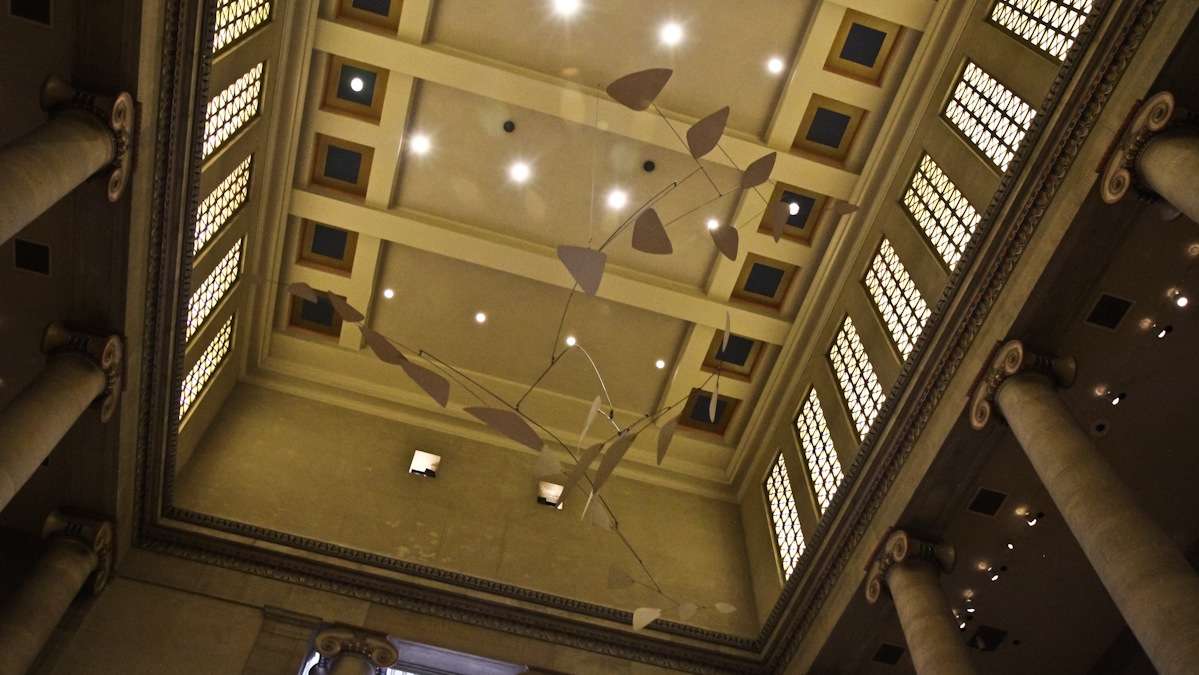

The mobile 'Ghost' hangs in the Great Stair Hall of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

-

-

-

-

Three generations of men named Alexander Calder have graced Philadelphia with their remarkable creativity, yet most locals pay them no attention. Only the youngest has earned international acclaim, but all three were among the best sculptors of their time.

Three generations of men with the same name have graced Philadelphia with their remarkable creativity, yet most locals pay them no attention. Only the youngest has earned international acclaim.

The three men are Alexander Calder. The eldest, Alexander Milne Calder (born 1846 in Scotland, died 1923 in Philadelphia) designed the statue of William Penn on top of City Hall and most of the other amazing and amusing pieces below.

His son, Alexander Stirling Calder (1870-1945), designed the Swann Memorial Fountain in Logan Circle, a straight shot out on the Ben Franklin Parkway.

The third, Alexander “Sandy” Calder (born in 1898 in Lawnton, Pa., 5 miles from the capitol dome in Harrisburg, died in New York City in 1976), sculpted massive outdoor steel pieces and invented mobiles. This city was his home only briefly, primarily in 1909, when he attended Germantown Academy for a few months. But wise Philadelphians still consider him a native son.

Three local experts explain how the Calder legacy has influenced Philadelphia and beyond.

Calder I

Philadelphia’s City Hall, commissioned in 1871 — the city’s biggest architectural commission to date — took 30 years to build. During most of those years, Milne Calder was designing its 250-plus statues. Hyman Myers, a local, nationally recognized architect with strong expertise in historic preservation, calls this “a significant, incredible amount for any sculptor to do and for any building to have.”

Calder’s, and perhaps the city’s, sculptural masterpiece is the statue of Penn, city founder. Facing northeast, the bronze Penn is 37 feet tall. He weighs nearly 27 tons. Most of Calder’s pieces, which he designed in plaster and which cutters forged in white marble, are life-sized or bigger. Myers praises Calder’s concept of an international theme, rather than images of local dignitaries — except for Penn. Calder sculpted ideas, such as “south,” “animals,” “flowers” and even “people.” On the north side, one sees a Caucasian man; on the east, Asian people and Indian elephants; on the West, buffalo.

Calder’s carvings are “significant in their execution,” says Myers, who pronounces Milne Calder the most significant of the dynasty within Philadelphia.

Calder II

Stirling Calder made his mark with the Swann Memorial Fountain at Logan Circle, where 19th Street meets the Ben Franklin Parkway. In “The Fountain of Three Rivers,” three bronze Native Americans recline among (sometimes) sky-high jets of water.

Laura S. Griffith, assistant director of the Association for Public Art, formerly the Fairmount Park Art Association, says that Stirling Calder’s ingenuity evolved from his father’s ornamentation. “Stirling Calder showed signs of modernism. As in art nouveau, his images were more stylized, less truly exact.” This, she says, was the essence of his excellence.

Classifying Stirling as “one of most important early 20th century sculptors and teachers,” Griffith points to his “Shakespeare Memorial” (1926), on the northwest corner of Logan Square; and his “Sundial” (1903) on the Horticulture Center grounds in West Fairmount Park. He studied in Philadelphia public schools and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA). He taught at PAFA; a school of industrial arts that is now part of the University of the Arts; and at the Pennsylvania Museum, now the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Beyond Philadelphia, Stirling Calder served as acting chief of sculpture for the Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco, which opened in 1915. Sixteen years later, the U.S. government donated Stirling’s sculpture of Leif Erickson to Iceland — to commemorate the 1,000th anniversary of Iceland’s Althing, the world’s oldest parliament. That’s certainly not all.

“We are so fortunate to have these collections of Calders,” says Griffith. “I can’t think of any other city that has three generations of artists like that. The work of all three is connected but also different. It reflects what was going on at the time they were creating. And all three were among the best sculptors of their time.”

Calder III

The third Alexander Calder, called Sandy, grew from his American sculptural roots into a horse of a completely different color. Beginning in the early 1930s, Sandy cut out the shapes of birds, fish and falling leaves, creating what Robert Cozzolino, senior curator and curator of modern art at PAFA, calls “floating, three-dimensional worlds in constant flux.”

According to Cozzolino, Sandy’s primary innovation was designing statues that move freely in natural currents of air. They are kinetic. They are mobile. The French artist Marcel Duchamp, dubbed them “mobiles.” The name stuck, and they are among the most-emulated works of art anywhere. Think patios and baby cribs.

Cozzolino: “By introducing movement, Calder differentiates mobiles from traditional three-dimensional sculpture.” He started with industrial materials, like wire and steel, and “introduced the idea of chance. You can design a mobile to have shapes and things hanging, but once you add flux…. What you see is not what others see, because weather and gravity itself — and even people walking by — make it unique at each moment.

These ideas had a huge impact on other art forms, says Cozzolino. Calder consorted with writers, who tried to emulate his spontaneous creativity. “He hung out with surrealists, though he never called himself one. He forged a kinship with artists in various media,” many of whom absorbed the idea of flux into their own work.

“Calder had a sense of humor and wasn’t afraid to show it in his art,” says the PAFA curator. “He had his own workshop at age six. He understood children and childhood. He seemed not to have all the baggage that most adults have. For the rest of his life, he was able to tap into that childlike wonder.”

Calder’s major influence was in Paris. Not much of his work is visible locally. His “Ghost” mobile (1964) hangs in the main stairway of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, looking out over the works of his paternal ancestors. “White Cascade” (1976) graces the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia. PAFA has a major piece, and Swarthmore College has a few. Sculptures weighing 30 to 50 tons don’t blow away in a stiff wind.

Every genius attracts detractors. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art is showing a Calder retrospective through July 27. I was fortunate to see it. At the entrance, guards tell visitors not to blow on the mobiles, which is senseless and counter to the artist’s wishes. Inside, a wall blares a Sandy Calder quotation: “Just as one can compose colors, or forms, so one can compose motions.” But some curator knows better than the creator.

A Wall Street Journal review by David Littlejohn of the exhibit included this stupefying put-down:

“Calder suffers the dubious fate of being too recognizable and — after ordinary viewers of the 1930s and ’40s grew accustomed to abstract art — too easy to like.”

Harrumph. Laura Griffith says all three generations of Calders “worked on a monumental scale with grace and elegance.” All are welcome in Philadelphia.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.