Fútbol dreams: A youth soccer coach connects South Philly through wins

As a child growing up in Mexico, Luis Uribe dreamt of a future playing fútbol. Decades later in Philadelphia, he uses the game to connect to his community.

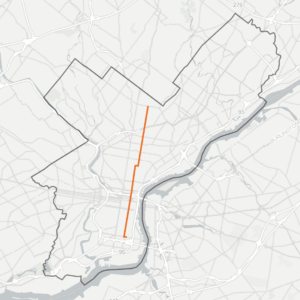

This story is part of The 47: Historias along a bus route, a collaboration between WHYY’s PlanPhilly, Emma Restrepo and Jane M. Von Bergen.

This article is written in English. To read this article in a combination of English and Spanish, click or tap here o para leer este artículo en español, haga clic o toque aquí.

When Luis Uribe was growing up in Puebla, Mexico, soccer, or fútbol, as it is known in every Latin American country, was his life.

It still is.

“When I was young, I loved soccer,” Uribe said. “Every Sunday I played soccer.”

So, when he came to South Philadelphia nearly 20 years ago, the first thing Uribe did was try to find another Sunday game. He’d go to the park, and sure enough, he found fútbol — and friends.

“At that time, a small league for adults began to be made and well, I was delighted,” he said. “I joined that league because it was what I wanted — to play soccer.”

Uribe had no idea that those modest pick-up adult leagues would turn into a big fútbol program for 80 families, with many enrolling three or four children. Most games are played at the Capitolo Playground on Ninth Street in South Philadelphia, just two blocks away from the Route 47 bus.

The fútbol players? They call themselves the Wolves, or Los Lobos.

“At this moment, at the Club Deportivo Los Lobos, we have approximately 180 children,” he said.

Uribe is the main organizer, channeling players into teams by age and abilities – edades y habilidades. Uribe tries to make sure the players on each team, in each age bracket, have roughly the same abilities, so the games can be competitive. “No team has better players,” he said. “No team is disadvantaged.”

Uribe also coaches the best players in travel teams. Los Lobos compete in many regional tournaments — in Delaware, New York, New Jersey, Atlantic City, and Reading.

And they win. The team of children under the age of nine and the under-12 team both took first place, becoming the city champions in a Philadelphia-wide winter tournament. The girls’ team came in third.

“So, I am super happy with it,” Uribe said.

Like most youth sports leagues, Los Lobos counts on parents for support – shirts, cones and equipment. And Uribe himself has bought more than his share of soccer balls.

“But the parents are the ones who contribute the most,” he said. “They donate a ball per family or they donate a packet of cones or all the equipment we need to train, which is not much. We need a little more, but everything is bought by the parents. The shirts — they also pay for them. Yes, basically, the parents and I are the ones who are helping.”

Like young athletes worldwide, Uribe himself dreamed of playing for his favorite team, or equipo. Of course, that would be Barcelona. But, as an adult, he had to admit the sad truth to himself.

“I can tell you that to score goals, I have two left feet and I’m not that good.”

Even though Uribe says he played like he had two left feet, he still hopes to fulfill his ambitions by finding a fútbol star among his Los Lobos players. “I’m a dreamer. I like to dream big and I keep dreaming. So far I have not achieved what I have [dreamt],” he said. “I would also like … my children to dream. Why not play for Barcelona?”

Meanwhile, Uribe, a mechanic and cook, keeps himself busy at Los Lobos’ home field: the Capitolo playground. The playground anchors a neighborhood, or vecindario, that has always been home to immigrants like Uribe. Capitolo sits at the southern end of the Italian Market, named after the Italian immigrants who once lived above their stores. Now there are also Mexican, Cambodian and Vietnamese markets nearby.

In 2000, when Uribe arrived in South Philadelphia, Mexicans were just beginning to move into the neighborhood – most of the Latinos living there were Puerto Rican. About half of Uribe’s neighbors were white. By 2018, Mexicans were the dominant Latino group. At the same time, more whites and Asians were moving in, while the Black population remained about the same, around 10%.

Black, white, Asian, or Latino, everyone plays fútbol.

“We have all nationalities,” Uribe said. “We have Chinese, we have browns [Blacks], we have Central Americans, Americans. We have everybody, everybody.

Uribe, a father of four, appreciates the way fútbol keeps his kids active. “I can tell you that in families the role that soccer plays is that children are not so attached to television, the telephone or electronic equipment,” he said.

But, in a neighborhood like Uribe’s, fútbol serves a larger purpose – bringing together, or juntos, children and families from all different countries and groups. The children run, play, and make friends, or amigos. And the families become amigos as well. “In these 10 years that I have been in soccer, I have seen many families become friends here. They make new friends.”

Sitting on the sidelines, watching the games, the parents talk. Soon there are invitations to birthday fiestas and family celebrations. Friendships form. Relations deepen.

“The group that I have, they are all friends. They are invited to parties,” Uribe said. “Of course they don’t have parties at this time, but I can tell you that last year it was nice to see how parents and children make friends.”

To Uribe, this is the beautiful role that fútbol plays in his neighborhood.

“And that is a very beautiful role — that fútbol unites them. I think that personally, I have liked that a lot, apart from the fact that I love fútbol,” Uribe said. “I like to see how children love what we do, but also that part about families getting together is what I have liked a lot — and we are united now.”

When Uribe came to Philadelphia in 2000, he just wanted to play soccer like he did at home in Mexico, maybe finding teammates among the other Mexicans who lived nearby. But now it’s the connections fútbol builds among people, cultures and nationalities that excite him the most.

“I think I like it better when other people of other nationalities also join us,” he said. “We communicate and now we have parties. We are no longer separate. We all know each other and get along well. [No matter] how little we understand each other in English or that they understand Spanish, but I think that we try to communicate and get along.”

And, as Uribe says, “y nos llevamos bien, de maravilla.”

“And we get along. Marvelously.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.