From industry to abandonment, artist’s mecca to hipster haven, new exhibit tells tale of Northern Liberties

Affordable real estate brought artist Jennifer Baker to Northern Liberties in 1978.

“When I moved to this neighborhood, there was a lot of industrial space, and row houses, too, that were really, really cheap,” said Baker, who grew up in New York and came here to study at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. “A lot of artists moved in at that time – in the ’70s and ’80s. Despite the fact the neighborhood was going through a pretty rough period, we had a very vibrant artists community. And we all knew each other.”

That era of Northern Liberties, when a former industrial hub was discovered and adopted by many creative people without much money, is one of many that Baker gathered photos, stories and artifacts from for an exhibit she curated. Northern Liberties: From World’s Workshop to Hipster Mecca and the People in Between, is open now through Aug. 31, at the Philadelphia History Museum at 7th and Market streets. See previous coverage from Eyes on The Street here.

The exhibit is the fifth to be housed in the museum’s Community History Gallery, a space created “for historical, community, social service, arts and cultural organizations from across the city to present their histories and to tell their stories that contribute to the fabric of life in Philadelphia,” said Museum Executive Director and CEO Charles Croce in a prepared statement. Croce calls the Northern Liberties story one of “transformation and progression.”

It was the creation of the Community History Gallery that inspired Baker to assemble the exhibit on behalf of the Northern Liberties Neighbors Association. But she’s been chronicling the changing neighborhood around her for many years, often through her art.

When Baker first moved to her studio at 3rd and Green – a former textile mill that also once contained a pornography print shop – she concentrated on figurative sculpture. The high ceilings and freight elevator meant her installation pieces could be big. Then in the late 1980s or early 1990s, by then she also had a house on American Street, the neighborhood was “burning down around me,” she remembered.

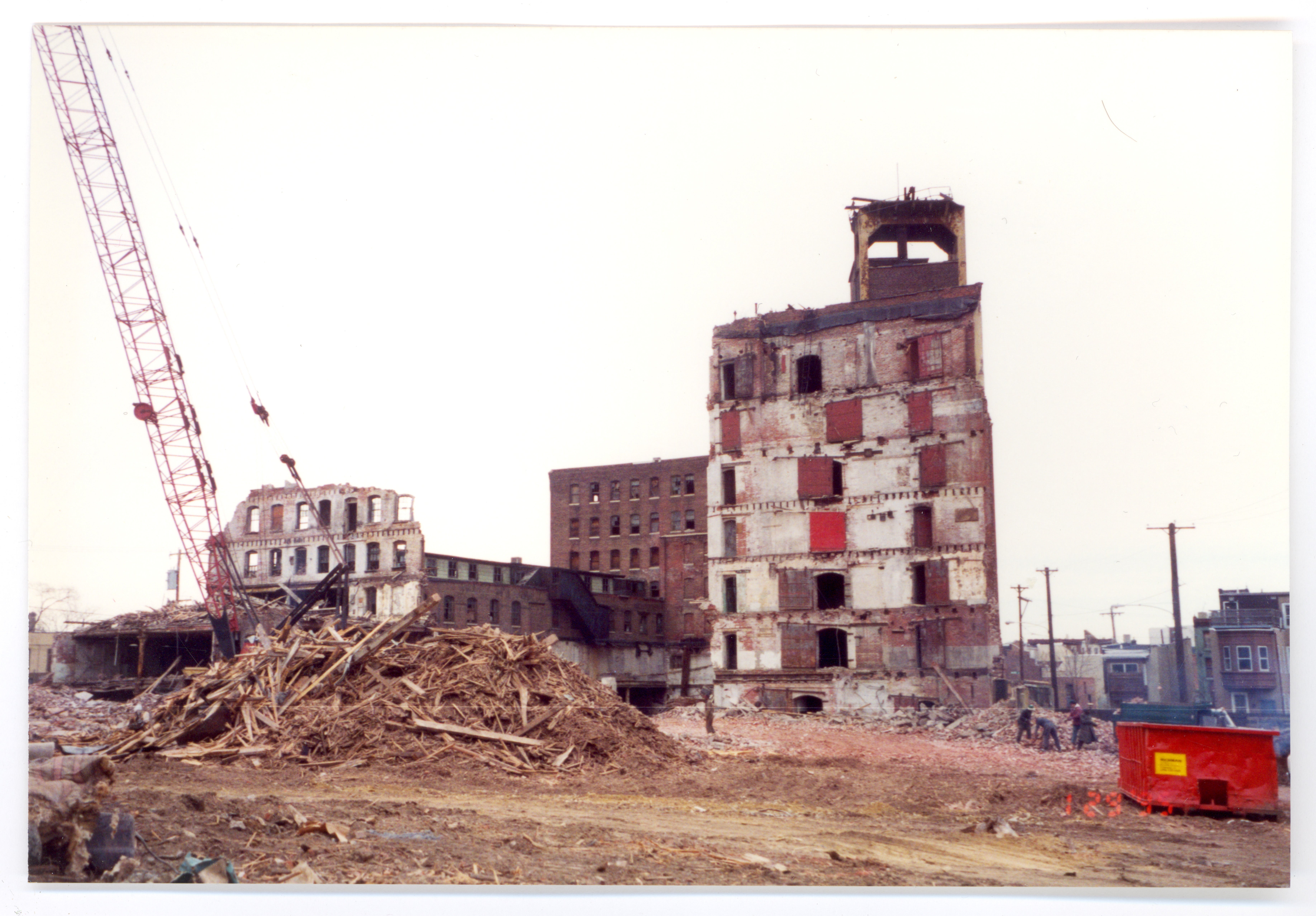

There were many fires of the sort she calls arson by neglect. Vacant properties were left open, and eventually, someone would start a fire inside. And the city was demolishing “whole blocks” for redevelopment. “It was so dramatic and so intense that I started documenting what was going on around me with mono prints and paintings.”

Things calmed down, and Baker returned to her other projects. But then in more recent years, the neighborhood began to change again, this time, with an influx of new development. “I felt like I wanted to document what was left of the old neighborhood, and the contrast. All the old churches … they’ve stayed the same, and people come back to the neighborhood for these churches. And the 19th Century small row houses. And then a (new) big, awkward building sticking up that didn’t fit visually.”

The transformation of the neighborhood continues.

“Northern Liberties is the fastest-growing neighborhood in Philadelphia,” said NLNA President Matt Ruben. But, he said, many people see his neighborhood only for The Piazza at Schmidts and the bars and restaurants. He hopes this exhibit will “help to paint a fuller picture.”

“It’s been all over the news media for the past five- to 10-years, and it is still one of the least understood neighborhoods.”

It was William Penn who set aside “Liberty Lands” on what was then the outskirts of the city for for farms and country estates. In the late 1700s, the neighborhood became more dense and urban. The 1800s brought water-powered mills and steam-powered railroads and Northern Liberties, like other communities on the Delaware River waterfront, became more and more industrial.

Most of the stories and artifacts Baker collected for this exhibit are from the 1950s to present, because she wanted to focus on years that are still remembered by some people living today.

She talked to many of them, and recorded first-hand accounts of the middle of the last century, when Northern Liberties was as residential as it was industrial. “People lived in the same neighborhood where they worked,” she said. “They did everything in the neighborhood. Their work, their church, their bar, everything was within a few blocks.”

Much of that industry, and many of those people, had left by the time Baker and the other artists in her cohort took up residence in Northern Liberties – that’s why living and working space came cheap.

“How did it change from that kind of neighborhood, with industries, to this real devastated emptiness that was in the 1970s? Why did that happen? Why did neighborhood empty out? Why did businesses close? I felt like I couldn’t do the exhibit until I understood that process.”

One exhibit video features Joe Ortlieb of Ortlieb’s brewery explaining in a 2009 interview what happened to his own business – a microcosm, Baker feels, for what happened to much of the industry in Northern Liberties, Philadelphia and many former industrial powerhouses.

“He had a state-of-the-art brewery. But then, the factory became outdated. He couldn’t compete with the national brands, and he would have had to spend so much to update, that at some point, he made a decision that it wasn’t worth it.”

In the video, Ortlieb is standing on American Street with the abandoned brewery behind him. Most of it has since been torn down. Baker watched in recent weeks as the progress of the demolition moved down the block, and row houses were constructed behind it. See a PlanPhilly story here.

Piazza developer Bart Blatstein, whom many credit with a good bit of the neighborhood’s transformation, is building the homes.

The walls of the Northern Liberties history exhibit showcase historic photos and explanatory text which illustrate living and working in the neighborhood and how it has changed over time. These include images of large fires and demolition, of shopping districts and the Northern Liberties Hospital. The display and the graphic art for the exhibit was done by Jordan Klein.

Objects on display include metal works by blacksmith Leonard Fector and the tools he used to make them at his shop at Bodine and present-day American Street. Fector worked from the late 1800s through about the 1930s, Baker said. Yet friends of hers found these artifacts of his life when they purchased the property. There’s also a red vinyl record made by Discmakers and discovered, intact, when tree pits were dug at Liberty Lands Park.

At the heart of the exhibit are the stories Baker collected from people who live or work in the neighborhood, or once did.

In addition to those presented on video, Baker put written stories into two books, one of which focuses on the neighborhood’s artists.

While artists and artisans remain in the neighborhood, “many have moved north to Fishtown or to Kensington,” she said. She asked those who migrated north why they left. “It’s gotten very difficult (to stay), because it’s gotten very expensive,” she said. “The changes that a lot of people look at – the new bars and restaurants – are wonderful. But there’s a downside. The population here is really changing.”

While the exhibit has opened, it’s not finished, Baker said. She’s collecting more stories.

Baker realized when she first thought about telling her neighborhood’s story that “no matter what piece I tell or how I tell it, every person who sees it is going to think it’s not exactly right,” she said. “That’s why I had the idea of having people be able to keep adding stories. All together, with all our points of view, we’ll build a deeper understanding.”

Have your own story of life or work in Northern Liberties? You can email it to Baker at jlpbaker@gmail.com, or share it live at the Tell Your Northern Liberties Story event, 6 p.m. March 24 at the Rodriquez Library, 600 W. Girard Ave.

Other events include Northern Liberties in Words and Film, Readings about Northern Liberties by Nathaniel Popkin, Stephan Salisbury, Elaine Krasnow Ellison, and Harry Kyriakodis from their books. And a screening of Northern Liberties: Destitute Urban Carnival Reborn! A 30-minute film by John Thornton.

Future events will be announced as they are scheduled. For more information, visit the museum website.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.