Founder moving on after 27 years of keeping Philly folk traditions from slipping away [photos]

ListenFolklorist Debora Kodish founded the Philadelphia Folklore Project 27 years ago as a place where people congregate, exhibit, exchange ideas and plan far-reaching grassroots projects.

Imagine a treasure trove of recordings, documents, artifacts, photos and even embroidered tapestries that tell the stories of Philadelphia’s cultural traditions and experiences. From immigration to social movements, protests to demonstrations, drumming circles to needlework groups, they’re all in one place. It’s not a library or a museum but the archives of the Philadelphia Folklore Project.

The PFP is located in an unassuming row house in West Philadelphia, identified only by a modest sign. Inside, it’s another matter. A large living room is both a gathering place and a gallery. A dining room, with a table covered by the ubiquitous red-and-white oil cloth, pays homage to the activist couple who owned the house. The walls are covered with political posters calling people to action and protest.

Upstairs are the offices and file cabinets that contain the 60,000-piece archive.

Folklorist Debora Kodish founded PFP 27 years ago as a place where people congregate, exhibit, exchange ideas and plan far-reaching grassroots projects. She wanted to follow in the best tradition of folklore as a voice of people in their daily struggles for social justice.

From African-American ancestors to Liberian songs for peace

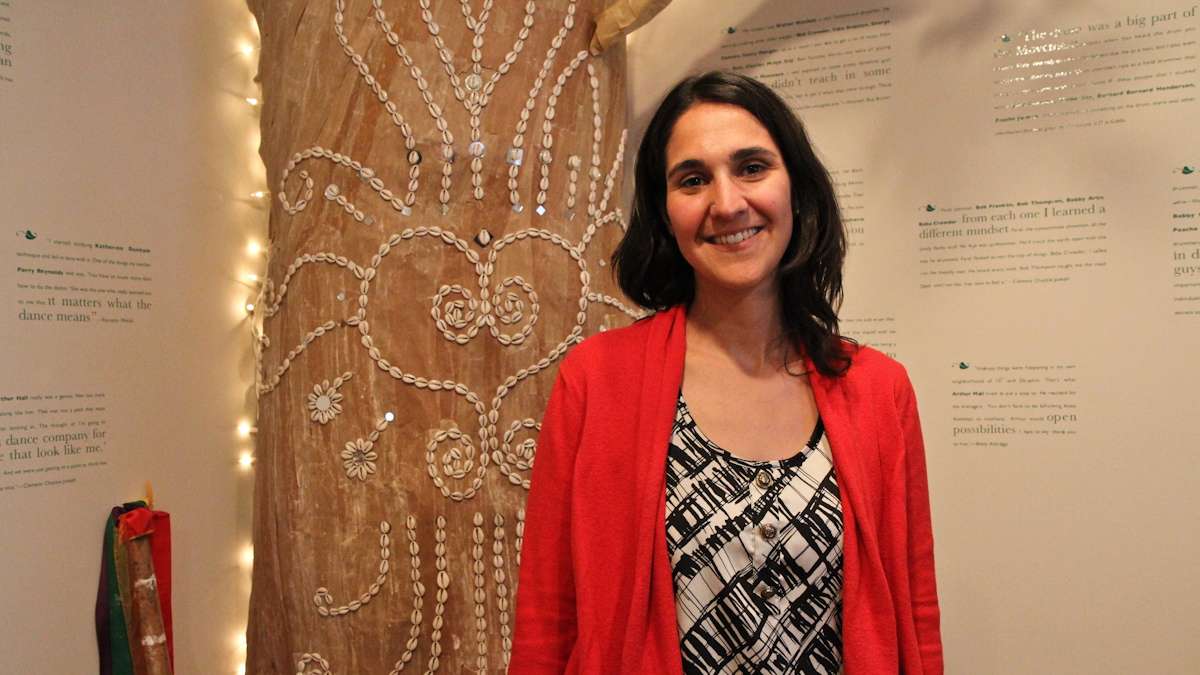

Today, the exhibition area is occupied by a large symbolic tree that honors African-American ancestors, part of a collaborative work that is just winding down.

The focus now is on a residency by the Philadelphia-based Liberian Women’s Chorus for Change.

“It’s a group of women who became active during the Liberian civil war and started working for peace,” said Kodish. “They’re incredible singers, and they’re using traditional songs, and re-contextualizing them to deal with domestic abuse and violence in their immigrant communities — and to push for alternative ways to help one another.”

The singers approached the project to tackle the family conflicts that come when women’s roles change in a new country and subvert tradition. Balancing the need to preserve traditions while adapting to new models is a common tension for immigrants and one of the PFP’s core mission.

In this 27th anniversary, Kodish is passing the baton to Selina Morales a folklorist who has been working at the organization for the past four years.

Morales says that folk traditions have to be relevant today and, “because of that, they’re projected into the future, to what people want to see, what people want to continue, so it’s really a commitment.”

The commitment manifests in many ways, adds Morales, who spent her first years at the center getting a sense of the holdings in the project’s vast archive. The PFP diligently preserves the stories and folk narrative materials created here by immigrants artists.

“There’s a beautiful seven-foot-long Hmong story cloth that chronicles the migration and displacement since when they started in China, moved to Laos, refugee camps in Thailand, and then Philadelphia,” she said.

There was also a series of needleworks taught by elder Palestinian refugees to younger artists that depict symbols and stitches from towns that are no longer there.

Both Morales and Kodish see the PFP as a living, vibrant organization that breathes, so to speak, to the rhythm of different communities. One vivid example is a documentation project proposed by the organization Asian American United. It focuses on the 2009 student boycott at South Philadelphia High School as a protest against violent attacks, racial harassment and the school district’s initial response.

“What they wanted to do,” said Morales, “is to take a minute to reflect upon what they learned during that organizing and they wanted to write about and create into an exhibition as an example of how traditions of organizing are passed on within a community.”

The result was the exhibition “We Cannot Keep Silent.” It’s a wall populated by photos, pamphlets and written testimonials from the participants.

As Debora Kodish retires from the Philadelphia Folklore Project to write and perhaps to rest a bit after 27 years of bringing people together and organizing festivals, she’s reflecting on the project’s legacy. She delights in the fact that it has made sure people and communities that are so busy finding their place in society don’t cast aside their folk traditions.

“So we are here to tell them with great passion and conviction that this is really important, you might want to hold on to this,” she said. “To have in multiple generations in a family people who know how to weave or who know the song traditions and the epic traditions, this is incredibly valuable knowledge and an incredible resource, an asset.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.