For President Trump, national security is all about … him

The president and his allies have denounced his critics for criticizing Donald J. Trump.

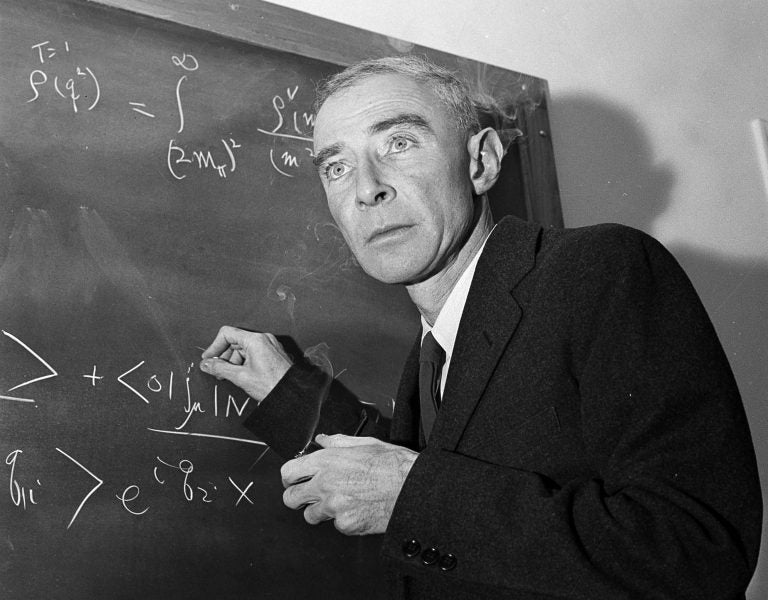

Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer, creator of the atom bomb, is shown at his study in Princeton University's Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, N.J. He was accused of having communist sympathies. (AP Photo/John Rooney, File)

When President Donald Trump threatened to strip security clearances from former officials who oppose his Russia policies, worried observers were quick to invoke the “Red Scare” of the McCarthy era. They pointed especially to atomic physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, who lost his security clearance in 1953 because of his ties to Communists and “fellow travelers.”

Nothing that has happened so far rises to the horrors of McCarthyism, which remains one of the greatest stains on the American past. But, in some ways, Trump’s threat is even worse. However unjust, the attacks on Oppenheimer and others were framed as efforts to protect the United States from a foreign enemy. But Trump has dispensed with all of that, making national security all about him.

Witness Trump’s warning that he might remove security clearances from former CIA directors Michael Hayden and John Brennan, former national security adviser Susan Rice, and former national intelligence director James Clapper. (Trump made the same threat regarding former FBI officials James Comey and Andrew McCabe, but neither retains a security clearance.) At no time did Trump or any of his aides suggest that these people posed an actual security danger to the country. Instead, Trump’s camp denounced his critics for … criticizing Donald J. Trump.

“Making baseless accusations of improper contact with Russia or being influenced by Russia against the president is extremely inappropriate,” declared White House press secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders. “And the fact that people with security clearances are making these baseless charges provides inappropriate legitimacy to accusations with zero evidence.”

Translated: We don’t like what you’re saying about the president. But we know you have a security clearance, which seems to enhance your status. So the president is going to punish you, by taking away your clearance.

Even at the height of the Red Scare, no one went that far. To be sure, victims often lost their clearances — and their jobs — because of their political opinions and affiliations. But the justification was always about the national interest. Potential subversives had to be purged because they endangered the security of the country, not the personal agenda of the president.

Indeed, both Harry Truman and Dwight Eisenhower expressed deep misgivings about the Red Scare. Privately, Truman said he wanted to find a way to stop the “un-American activities” of the loyalty boards that conducted investigations. Eisenhower told a supporter that Sen. Joseph McCarthy was a demagogue and a “pimple on the path of progress.”

Both presidents acquiesced in the injustices of the McCarthy period, lest they be seen as soft on, yes, national security. But they weren’t the main engine of the movement, which had deep roots across American society and politics. In the federal government alone, more than 2,000 people sat on different departmental and agency loyalty boards. Their job was to ferret out anyone who might harbor any criticism or ambivalence about America.

So at one hearing, a federal employee was asked whether he believed in government ownership of utilities, and if he thought that “workers in the capitalist system get a relatively fair deal.” Another was asked what he thought about “racial equality.” The logic went like this: If you like things that the Reds like, you might be Red yourself.

Or you could dredge up the person’s past, to see if they had Communist associates or affiliations. And that’s what sank J. Robert Oppenheimer, who had taught at the University of California Berkeley in the 1930s. Then, as now, Berkeley was a lodestar of radical politics. So it’s hardly surprising that Oppenheimer — although never a Communist himself — had plenty of students, family members, and even an ex-girlfriend who had been in the party.

Oppenheimer survived four security hearings before he was finally stripped of his clearance in 1953, probably because he had opposed the development of the hydrogen bomb. After the Cold War ended, Soviet archives revealed that the KGB had tried to recruit Oppenheimer, but he turned them down. He wasn’t a subversive; he was a victim of un-American activities, by persecutors who saw him as insufficiently American.

Oppenheimer continued to write and lecture around the world, until his death in 1967. But other casualties of McCarthyism weren’t so lucky. For example, nearly 3,000 longshoremen and seamen lost their jobs after failing the Coast Guard’s security screening, and some of them never worked again. The people at the bottom had the most to lose.

And that’s still true, of course. Trump and his aides have suggested that John Brennan, Susan Rice and his other critics are somehow profiting off their security clearances. But even if they lose their clearances, Brennan and Rice — like Oppenheimer — will be OK.

What about a midrange CIA officer who is considering blowing the whistle on a corrupt boss, or an FBI agent who has found dirt on Trump himself? What will prevent him from revoking their clearances, too, and destroying their livelihoods?

At least during the McCarthy era, we imagined that invocations of national security would help secure the nation. But President Trump has done away with that pretense, once and for all. He is trying to protect himself, not America. And I’m not even sure he knows the difference between the two.

_____

Jonathan Zimmerman teaches education and history at the University of Pennsylvania. He is the author (with Emily Robertson) of “The Case for Contention: Teaching Controversial Issues in American Schools” (University of Chicago Press).

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.