Following a true American original: Horace Pippin

ListenSelf-taught, American artist Horace Pippin grew up in West Chester, Pennsylvania.

He lived through World War I, segregation and loss, as well as success, before his death in 1946.

He created his own visual language that spoke about African-American life between the wars. And he is celebrated as a true American original in the major retrospective “The Way I See It” at the Brandywine River Museum.

Horace Pippin returned from World War I with a crippling arm injury from a sniper shot and images of mayhem in his mind.

It’s believed that a wounded Pippin tumbled into a trench, where bodies fell on top of him and prevented him from moving, said Kimberly Camp, writer, artist and former director of the Barnes Foundation. “That imprints your mind in a way that’s never going away.”

But as it happened with many American soldiers, in France Pippin also experienced a different way of looking at art, Camp added. It was considered an integral part of the fabric of a community, “which wasn’t the case in the United States at the same time,” she said.

Pippin had been interested in drawing since he was a child. His European experience strengthened his resolve to become an artist.

On the homefront

As a soldier in the famous all-black 369th Infantry Regiment, he was awarded the French Croix de Guerre and a pension that allowed him to take 10 years to relearn how to draw and paint with his left arm holding the other. He started drawing his surroundings in West Chester.

He painted domestic scenes of families gathered in small houses, children playing outside and everyday occurrences in his community — from church life to work life.

Part of the Brandywine Museum retrospective is a guided tour of Pippin’s West Chester designed by Mark Tajzler. The tour stops at the city’s courthouse, which looks almost exactly the way Pippin painted it in the 1950s.

At a street corner, Tajzler pointed out where Pippin painted “Harmonizing,” in which he shows a group of singers practicing in an otherwise sleepy scene.

The tour is part of the first retrospective of the artist’s work in 20 years. Aptly titled “As I See it,” the 65 works in the exhibition reveal a narrative visual style that shows Pippin’s sophisticated use of colors and forms.

“He has a characteristic boldness to his style and use of color that pushes him beyond what most people think of self-taught artist or naifs, pushes him squarely in the category of the modernist.,” said Camp. “A lot of people have said his brushwork is a lot like van Gogh brush work.”

Historical sensibility, modern suffering

Audrey Lewis, curator of the Brandywine Museum show, said Pippin’s interest in American history is revealed in his thematic series.

“They are often about subjects that have meaning to African-American citizens, especially at that time — the story of Abraham Lincoln, the story of the John Brown, the abolitionist. Those were his major history paintings, and he did series on both of them,” Lewis said.

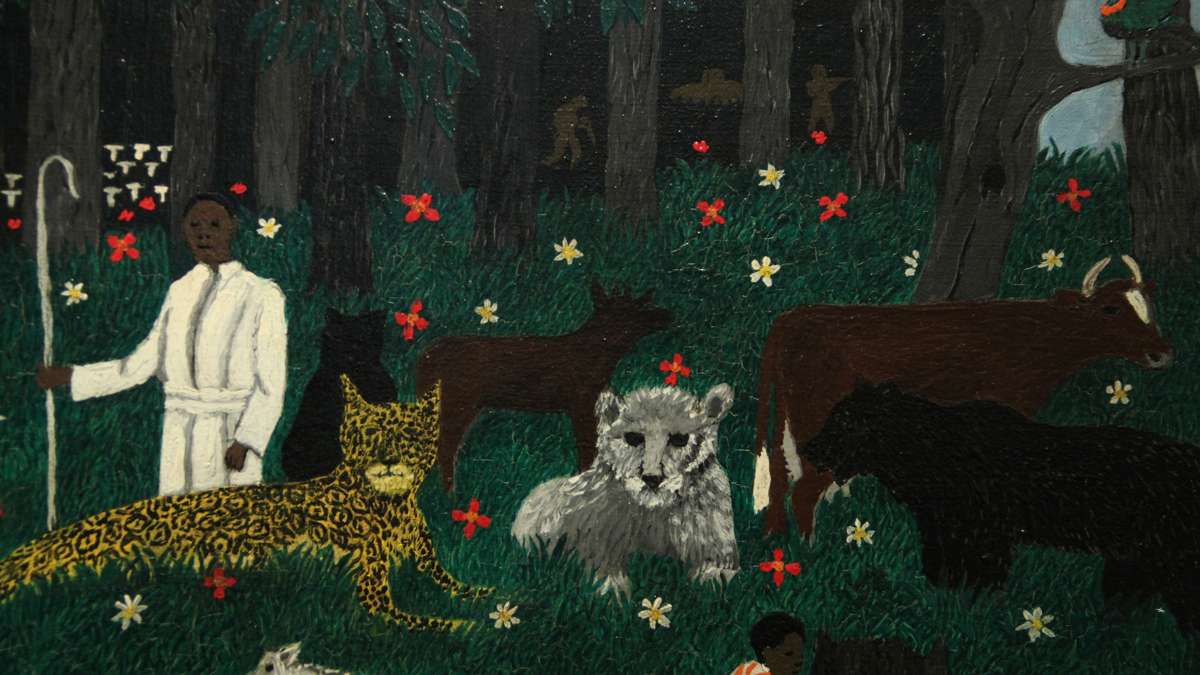

Pippin also did various paintings based on his war experiences. Reminiscent of Edward Hicks’ famous “Peaceable Kingdom” series, some aspects are anything but peaceable.

“They remind you of war, racism, what’s going on in the South and suffering in general,” Lewis said.

In one of the “Holly Mountain” paintings, you can see the lion and the lamb, wolf and deer, a shepherd dressed in white and children playing. But in the forest behind that scene, soldiers and tanks lurk in the shadows, while bodies hang from trees as reminders of lynching.

Pippin was very deliberate in his use of images and did a lot of research before embarking in a work of art. In his 1938 essay, “How I paint,” Pippin wrote that he goes over every picture several times in his mind so when he is ready to paint “I have all the details I need.”

Catching Barnes’ attention

Pippin was a successful artist and his work was purchases by collectors, private and public, partly because he attracted the attention of Dr. Albert Barnes at a gallery show in Philadelphia. The influential collector invited him to attend classes at the Barnes Foundation, and they became close friends. Many works from Pippin are still on display at the foundation’s gallery.

Art writer Judith Stein, who curated the first retrospective of Pippin’s work 20 years ago, said his success was well-earned.

“We are all of our time and what we write and paint is very specific to our time. The great art goes from that specific to some universal, and that was that quality in Pippin, which leads me to consider him one of the finest American painters of the 20th century,” she said.

The retrospective, “Horace Pippin: The Way I See It,” is at the Brandywine River Museum in Chadds Ford until July 17.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.