Focused ultrasound treats tremors from Parkinson’s disease

The FDA recently approved a procedure to ease the trembling caused by Parkinson’s that doesn’t involve invasive surgery and cutting into a patient’s head.

Listen 2:02

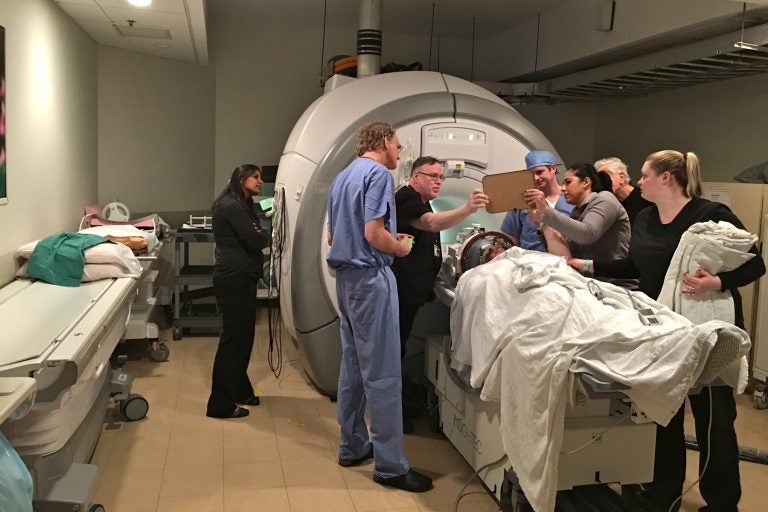

Dr. Gordon Baltuch and his team check on a patient throughout a procedure that uses a beam of ultrasound waves to stop his hand from trembling. (Kyrie Greenberg/WHYY)

Perry Collier was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease about 11 years ago, and he’s lived with the tremors associated with it ever since.

“It’s very similar to shaking when you’re cold. If you fell into an icy lake and they pulled you out like teeth chattering and arms shaking and legs shaking. It’s pretty much the same,” he said.

Collier, who is from South Jersey, has medication he can take three times a day, which kind of helps, but the tremors still get in the way of his everyday life.

“I think it’d be nice not to spill water over myself when I get a drink and not to poke myself in the eye when I try to put eye drops in,” he said.

Researchers estimate that more than 600,000 people above the age of 45 in the U.S. have Parkinson’s disease, and that number is expected to rise.

A new noninvasive surgical procedure the FDA approved for Parkinson’s in December could help with tremors from the disease. Collier was waiting to undergo the procedure last week at Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia.

The tremors happen because there’s a problem with a specific part of the brain. The procedure focuses ultrasonic waves right at that point, to burn a tiny hole, millimeters big, in the area associated with the tremors.

Gordon Baltuch, Collier’s surgeon and a professor of neurosurgery at Penn Medicine, has done the new procedure on three Parkinson’s patients thus far. He explained that, unlike the previous standard treatment, this new technique does not require cutting into the patient’s head. Instead, it focuses ultrasonic waves onto a single point.

“It’s very similar to … when you take a magnifying glass, and you make a small hole in a piece of paper with the sunlight … all that sunlight gets magnified at one point, and it burns [a] hole in the paper,” he said.

That takes place inside a magnetic resonance imaging machine, because, of course, you don’t want to burn a hole in the wrong spot.

After three hours, Collier came out of the MRI. The procedure targeted the part of his brain giving him a tremor in his right hand. That hand was now still, unlike his trembling left hand.

Collier burst into tears. “Tears of joy! I’m so happy!”

The focused ultrasound procedure costs around $30,000 according to Baltuch. It’s such a new procedure, he said, that insurers do not cover it, though he hopes that will change soon.

Right now, surgeons commonly address tremors in Parkinson’s disease by a technique called deep brain stimulation — cutting open the head and putting in a device that stimulates the parts of the brain that control movement using an electric current, similar to a pacemaker. Collier chose not to do this because of the risk of infections associated with the surgery.

On the other hand, deep brain stimulation is adjustable and can be turned up as the disease progresses, whereas focused ultrasound is permanent.

Caroline Tanner, a professor of neurology at the University of California San Francisco, said the focused ultrasound “can make a really big difference.”

But she added that there are other symptoms that affect the quality of life for Parkinson’s patients, such as slow movements and stiffness in the arms and legs. Researchers are still looking into whether they can address those symptoms by aiming the focused ultrasound at other targets in the brain.

Tanner said researchers are also working on gene therapies to rewire the brain to make medications more effective, targeting proteins that they think might be responsible for the progression of the disease, and identifying people at risk of Parkinson’s earlier.

Paul Fishman, a professor of neurology at the University of Maryland, said focused ultrasound with less energy can also open the blood-brain barrier for a limited time, which protects the brain but also makes it hard to get drugs there. Opening the barrier with focused ultrasound could make a difference in treating brain tumors, and Alzheimer’s disease.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.