Fiscal reform in Philadelphia faces a taxing problem

-

Developer Waterfront Renaissance Associates has plans for a 1,458-unit, four-tower residential and retail complex

-

Penn Park: beautiful, but not taxable

-

Fiscal reform in Philadelphia faces a taxing problem

Jobs behind the push to cut taxes

The competitive advantages of lower wage and business taxes are well documented.

A half century ago, when Philadelphia’s economy was still manufacturing-based, the high rates the city charged on wages and business activity weren’t deal-breakers, in part because moving factories out of town was a costly proposition.

But as manufacturing eroded and the U.S. economy became dominated by office and service jobs, employers found they could easily relocate outside of cities like Philadelphia, and thus avoid the burdensome wage and business taxes.

In all, Philadelphia has lost about 28 percent of its jobs since 1970, according to federal labor statistics, and Wharton economist and tax expert Robert Inman has shown conclusively that the city’s high taxes on wage and business are responsible for many of those lost positions.

And so Nutter’s task force reached the same conclusion as earlier commissions, and recommended a new tax mix “that relies less on mobile tax bases like jobs and businesses, and relies more on revenues from the City’s assets that cannot be moved: its land and buildings.”

“This is not simply a matter of lower taxes. Its shifting how we fund city government,” said Paul Levy, executive director of the Center City District and a member of the 2009 task force.

And that shift is already underway, though perhaps not as fast as Levy and other business advocates would like.

Beginning in 2014, the city plans to resume planned wage tax cuts that had been delayed when the recession hit. Last year, Council and mayor enacted bills that will give big tax breaks to small businesses beginning in 2013, as well as an across the board tax cut on the gross receipts tax that starts to phase in during 2015.

Meanwhile, Nutter and Council have raised property taxes three straight years. In the five years since Nutter took office, the share of the city’s total budget covered by real estate taxes has grown from 10.62 percent to 13.9 percent, a 31 percent increase.

Levy and a number of business leaders are now pressuring City Council and Nutter to do more, faster.

Next year, City Hall is slated to wrangle a second time with the property assessment reform known as the Actual Value Initiative. Levy hopes the looming debate turns into a wholesale rejiggering of the city’s tax structure.

That could be a tough sell. AVI – which is intended to correct the city’s wildly inaccurate and inequitable current assessment system – spooked council members in a big way during the last budget season, when it became clear that the post-AVI tax rate would be higher than many had anticipated.

Shifting a chunk of wage and business taxes onto property will drive that rate higher still. The big new real estate bills might be seen as a worthy trade to many property owners, so long as it comes with a commensurate reduction in other taxes. But it won’t be easy to convince a twitchy council of that.

The Mixed Blessing of tax exemptions

In some ways, Philadelphia’s abundance of tax-exempt property is evidence of what the city is doing well.

Philadelphia’s colleges, universities and hospitals are positively thriving, creating jobs in large numbers and expanding their physical footprints. But these institutions, like all non-profits, are exempt from paying property taxes. This is the case in every large city in America, but Philadelphia’s non-profit sector is far and away the biggest in the country.

In 2006, non-profits owned 10.8 percent of the total assessed value of property in Philadelphia. A survey of the 30 other largest cities that year by the Chronicle of Philanthropy found that the city with the next-highest non-profit exemption rate was Boston, with 8.4 percent. Most cities surveyed exempted less than six percent of the total value of their property to non-profits.

And yet it’s difficult to make the case that Philadelphia is actually worse off because of its abundance of big non-profits.

Consider the eastern bank of the Schuylkill River, where the University of Pennsylvania and the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia have recently acquired big tracts of land.

Before they were purchased by non-profits, those underdeveloped parcels paid taxes totaling $112,307 a year. Now they pay nothing. And yet the economic activity CHOP and Penn will eventually create on these parcels seems more than worth the tradeoff: construction jobs, research positions, shops and restaurants that will be opened to cater to these new facilities, and so on.

But the city and schools nonetheless feel the pinch. Citywide, property owned by hospitals and institutions of learning has an assessed value of $1.13 billion, enough to generate $107 million in annual property taxes. If, that is, the parcels were not exempt.

And it’s entirely possible, even likely, that we will discover the true value of tax-exempt property in Philadelphia to be much higher than it is recorded as of today. The city’s long-broken assessment system has some comically low values in its records for non-profit owned property. Consider 201 S. 32nd Street, better known as the 52,600 capacity Franklin Field.

According to the city’s current assessments, Franklin Field’s market value is just $1.78 million. If the Actual Value Initiative works as billed, properties like Franklin Field will be assessed at something closer to their true worth, and the tax-exempt slice of the total value of property in Philadelphia may well grow larger.

The city used to collect as much as $9 million a year from non-profits like Penn in the form of PILOTs, for Payment In Lieu of Taxes. But in 1997 state law changed, and cities like Philadelphia lost their leverage to demand PILOTs. Penn quit paying, and so did almost everyone else.

Their justification was simple enough. Universities like Penn make major contributions to the city through economic development, public services like a campus/community police force, subsidies to a local public school, and the redevelopment of huge swaths of property, some of which is leased to commercial enterprises that do pay taxes.

In these lean times, however, that may not be enough for City Hall.

This May, a new state Supreme Court ruling was issued that appears to put municipalities back into a strong position to demand that big non-profits pay up, or face expensive litigation. The Nutter administration hasn’t moved one way or the other yet, but is “examining its policy” in light of the ruling, said administration spokesman Mark McDonald.

Non-profits, however, are only part of the city’s tax-exemption problem. Government-owned land is also tax exempt, and Philadelphia has a chronic over-abundance of vacant, publicly-owned property. Until those properties get back into the private market, they will generate no tax revenue.

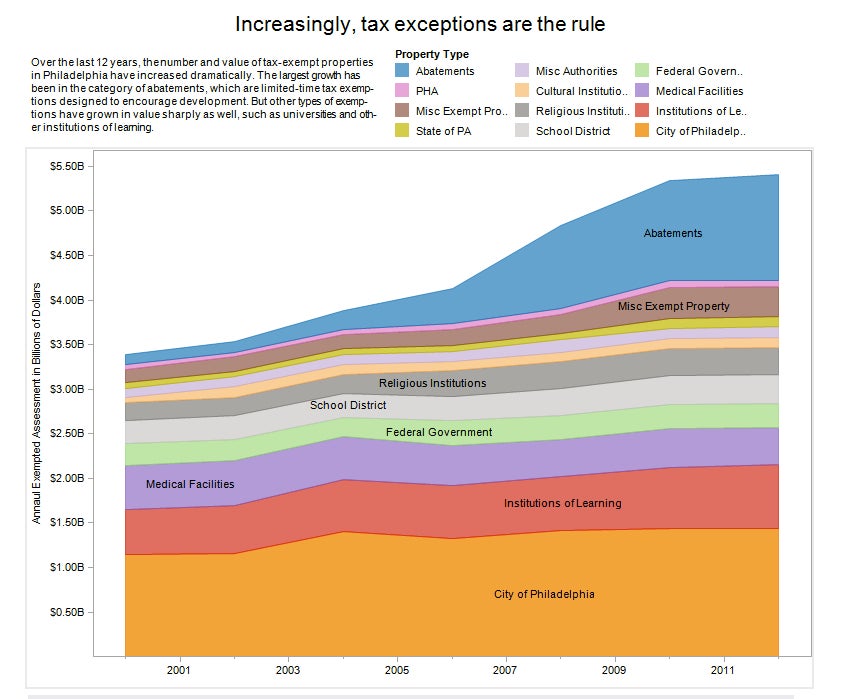

But the most explosive growth in Philadelphia’s inventory of tax exempt property has been in the category of abatements: time-limited tax breaks designed to make it less expensive for developers to build.

Twelve years ago, abatements accounted for only a small sliver of the total property value in Philadelphia – about $110 million. Today, tax-abated property is worth $1.19 billion, and the annual forfeited property taxes on those parcels tops $112 million.

Advocates of the abatement program contend that without the tax break there would have been far less development in Philadelphia over the last 12 years. And that, they argue, would in turn would have meant fewer people moving to the city, and thus less paid into city coffers in wage and sales taxes.

Strengthening the base

Still, there’s little doubt that, whatever their long-term benefits, abatements are a short-term blow to the property tax base. And indeed there are a number of signs that City Hall may soon scale the program back.

Clarke, who has tried and failed before to reduce the abatement benefit, is now Council President and better positioned to push his agenda. Last week, at-large Councilman Wilson Goode Jr. introduced a bill that would cut the abatement benefit in half, from a decade to five years. And Nutter, a long-time abatement advocate, appears to be having second thoughts.

“We are … looking at the city’s experience with tax abatements in connection with a broader discussion of the current mix of taxes,” McDonald wrote in an e-mail. “While it’s clear that abatements have spurred economic development for more than a decade, adjustments to our current law may be considered when the real estate market gains strength.”

City Council may also choose to tinker with the formula that determines how property taxes are charged. Some are open to the notion of a “land value tax,” a policy that calls for heavily taxing the land itself, while charging little for actual improvements to property.

Under such a reform, parcels located in high-value neighborhoods like Center City would be uniformly taxed at high rates, thus making it very expensive for property owners to sit on undeveloped land or surface parking lots. Some council members think a land value tax would work to the benefit of homeowners, shifting a larger share of the real estate tax burden onto commercial property owners.

Another option, though perhaps not a likely one, is to convince state lawmakers to pass new legislation authorizing the city to charge different tax rates to different types of property owners. In theory, that could make it easier to shift more of the increased property tax burden onto commercial real estate.

“If we had the flexibility to do that – which is something we are having conversations with the state about – then that’s something that would be given serious consideration,” Clarke said.

Other ideas could be in the offing as well.

Right now, however, Philadelphia has the nation’s most generous property tax abatement program, the weakest property tax collection system, and an inventory of tax-exempt property that is second nationally only to Washington D.C., where the federal government owns vast tracts of exempted land.

One or more of those conditions will likely have to change if real estate is to be the foundation of Philadelphia’s financial future.

“It’s really hard to imagine shifting all or even most of the business and wage tax burden onto 60-something percent of the property owners,” said at-large City Councilman Bill Green. “It’s probably not politically possible.”

Patrick Kerkstra’s article is part of a continuing partnership between The Inquirer and PlanPhilly. Since August 2011, that effort has produced a series of stories on the tax delinquency crisis in Philadelphia.PlanPhilly.com is an independent news-gathering entity covering the “built environment.” It is affiliated with Penn Praxis, the clinical arm of the School of Design at the University of Pennsylvania.

Contact Patrick Kerkstra at pkerkstra@planphilly.com or follow on Twitter @pkerkstra.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.