Fiber artist creates ‘Interwoven Stories’ with needle and thread

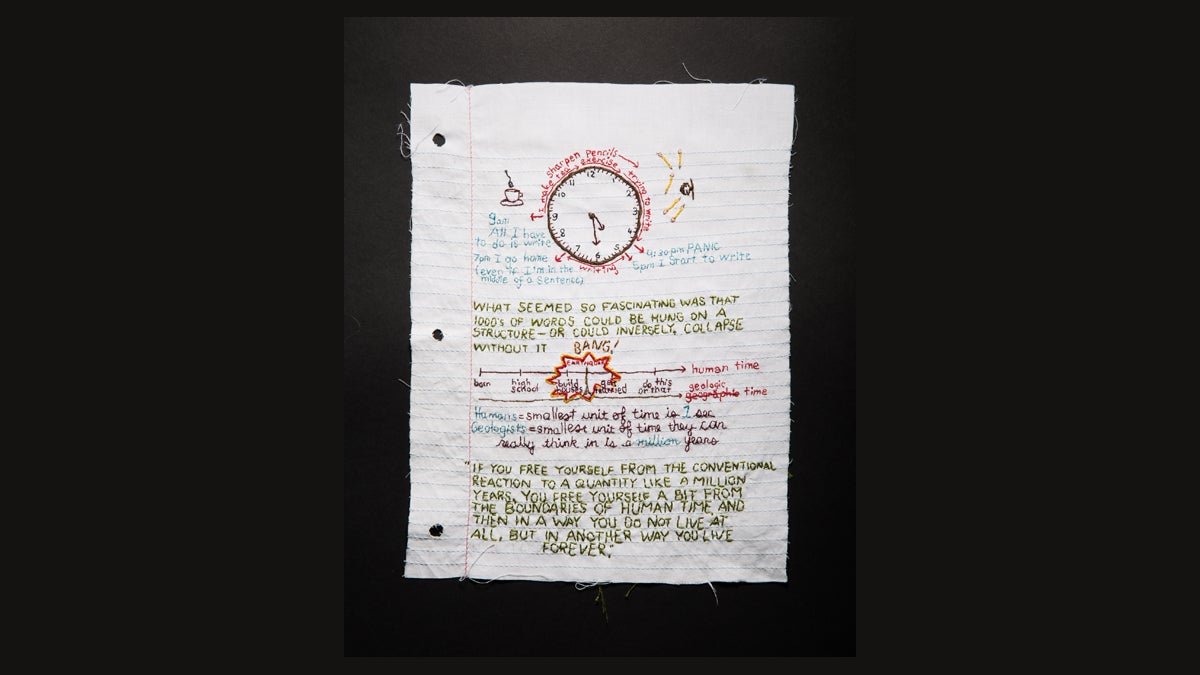

McPhee sampler by Diana Weymar

Participating in a community-wide art project hasn’t been this much fun since the creation of “Happy World,” the mural in the Princeton Public Library made by artist Ik-Joong Kang and comprised of square tiles embellished with artifacts contributed by area residents.

For “Interwoven Stories,” under the direction of Diana Weymar, the Arts Council of Princeton Spring 2016 Artist-in-Residence, participants have been invited to embroider a cultural map or a personal page that Weymar will compile into a larger body of work. “I wanted to create a project using an ‘ancient technology’ in a contemporary setting,” she said.

Participants have picked up their “pages”—an 8 ½-by-11-inch sheet of cotton muslin stitched and punched to look like a page from a loose-leaf binder—and started to sew. Weymar will be available to work help participants April 15, 2-5 p.m., at Princeton Public Library; April 16,1-3 p.m., at Robeson Center; and during Communiversity, April 17, 1-6 p.m., Robeson Center. The deadline to submit the finished project to the Arts Council is June 15, and the entire body of work will be exhibited in the Arts Council’s Taplin Gallery November 5-23.

Weymar’s 8-by-2-foot embroidered banner is on display behind the help desk at Princeton Public Library through April 18, and Every Fiber of My Being, a textile exhibit curated by Weymar, is on view at the Arts Council through April 17.

Sewing has become something of a lost art form, as our culture devalues the work, once considered women’s work. Ironically, as women perform more of the work formerly performed by men, laboriously produced handcrafts, made with love, are often remaindered in thrift shops and yard sales.

“Men are more than welcome to participate in the community project,” Weymar said.

“In a time of instant communication, disposable objects and an abundance of manufactured materials, what does art—if made with every fiber of our beings—say about who we are?” posited the Victoria, British Columbia, resident.

In her own work, Weymar uses family photographs, textiles and artifacts as memory materials, reworking fiction and poetry into the work, “documenting the impermanence of our unfolding lives.” She interviewed author and Princeton professor John McPhee for a McPhee sampler. It includes an embroidered clock with a schedule of the writing day, beginning with making tea, exercise, sharpening pencils. “9 am All I have to do is write/ 4:30 pm PANIC/ 5 pm I start to write/ 7 pm I go home (even if I’m in the middle of a sentence)”

Weymar, Princeton University Class of 1991, studied English and creative writing with McPhee, as well as Joyce Carol Oates, Russell Banks and Paul Auster. She met her husband, Princeton native Matthew Weymar, and worked as a set production assistant for a small independent film company in New York City.

After the birth of three of her four children—now 22, 16, 14 and 12—Weymar and her family moved to British Columbia. She has given up creative writing, but is still drawn to words. “I write really long e-mails,” she said. The embroidered works are another outlet for telling stories. “I have been balancing family life with my lofty ambitions,” she said. “I can go to a tournament and stitch while parenting.”

Both film and embroidery are visual languages, beginning with a sketch or story board. “For me, the stitched word and the handwritten word are intimately related. The typed word is vastly different. It’s about looking and watching but not about creating a shape. Both the written and stitched word reveal so much about the author. All typed words look the same; all stitched and written words are different.”

Children are no longer taught cursive in school, she observes, and many of us never see the handwriting of those we correspond with frequently.

Weymar tells her own story of growing up in a cabin in British Columbia through embroidery on a vintage textiles, inherited from her grandparents, including a little girl on a swing stitched onto an child-size cable-knit sweater. (The John McPhee sampler was stitched on her grandparents’ bed sheets.)

“My mother didn’t want all these textiles, she’s very active and travels,” said Weymar. The love of handcrafts often seems to skip a generation. “I was looking at Louise Bourgeois’s work, and at clothing worn by victims of Hiroshima at the University of British Columbia Museum of Anthropology. Through a light box you could see the stains and the burnings. It was so evocative and changed the way I looked at this clothing. It is a canvas for telling a story, but it took a while before I could work up the nerve to change the garment.”

She used photos from her childhood that had been deliberately staged and constructed to tell the story of how she and her family were living in the 1970s. Her parents raised their children in a primitive log cabin with no plumbing or electricity. “My father was tanning hide and my mother was washing outside. I was intrigued by the lifestyle, the adventure—they wanted to live off the land and be self-reliant. They each tell a different story, and it evolves over time.”

Weymar quotes writer Alice Munro: “Memory is the way we keep telling ourselves our stories and telling other people a somewhat different version of our stories.”

_____________________________________________________

The Artful Blogger is written by Ilene Dube and offers a look inside the art world of the greater Princeton area. Ilene Dube is an award-winning arts writer and editor, as well as an artist, curator and activist for the arts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.