Family of N.J. teen killed by train disputes suicide ruling, sues to prove kidnap-murder plot

It took less than a day, after Tiffany Valiante got hit by a New Jersey Transit train, for investigators to decide she committed suicide. Her parents never believed it.

Listen 4:11-

Tiffany Valiante’s family constructed a memorial near the tracks where she was killed. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Lawyer Paul R. D'Amato is working with the Valiante family to change Tiffany’s death certificate, and convince authorities that more investigation is needed into her death. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Tiffany’s father Stephen Valiante built a memorial in their yard where her nieces and nephews can come to remember her. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Tiffany’s father Stephen Valiante, sister Jessie Vallauri, mother Dianne Valiante, and sister Krystal Summerville stand in front of a volleyball court the family installed in the yard in memory of Tiffany. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Tiffany’s sister Jessie Vallauri, mother Dianne Valiante, and sister Krystal Summerville, stand near a memorial to her in the yard of the family’s home. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Tiffany Valliante’s family constructed a memorial near the tracks where she was killed. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Tiffany’s father Stephen Valiante, sister Krystal Summerville, and mother Dianne Valiante stand beneath a sign commemorating Tiffany near the tracks where she was fatally struck. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Flowers mark the spot where Tiffany Valiante was struck by the train in July of 2015. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Dianne Valiante holds a feather she found visiting the tracks where her daughter was killed. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

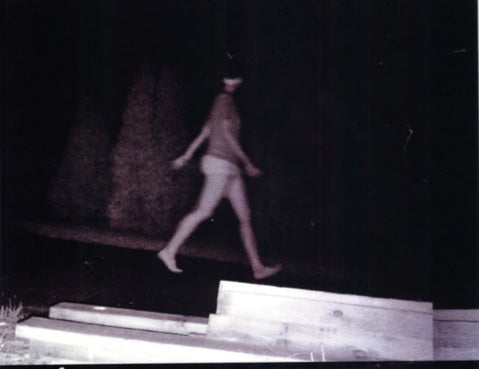

A cross marks the spot where Dianne Valiante found the shoes and headband of her daughter Tiffany. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Dianne Valiante explains how finding her daughters shoes and headband on the side of the road “hit her like a Mack Truck.” (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

It took less than a day, after Tiffany Valiante got hit by a New Jersey Transit train, for investigators to decide she committed suicide.

Her family never believed it two years ago when it happened, and not just because investigators’ conclusion was reached so quickly.

Instead, the family always suspected Valiante, an outgoing, college-bound 18-year-old volleyball star, fell victim to foul play the night she died. Her killer, they believe, hid his crime by hurling her into the path of an oncoming locomotive.

For two years, the family has fought for official investigative files, called in outside experts, and even found evidence the transit agency’s investigators missed, as they hunted for answers in her July 12, 2015, death.

Now, they’re suing.

Attorney Paul R. D’Amato filed a civil lawsuit Tuesday in New Jersey Superior Court asking a judge to change the Medical Examiner’s death ruling from suicide to undetermined and demanding a jury trial to air the family’s allegations of kidnapping, assault and battery, manslaughter, murder, conspiracy, and destruction of evidence.

They’re still not sure what happened to Tiffany. But they suspect someone snatched her from outside her Mays Landing home in Atlantic County, sexually assaulted her, and then pushed or chased her into the path of the train.

“You have parents, you have sisters, who have to live with the fact that some governmental agency concluded that their loved one committed suicide when the fundamentals of a suicide investigation weren’t done,” said D’Amato, who is handling the case for free. “There’s a wrong here we’re trying to right, for the benefit of them.”

He added: “We have no doubt that Tiffany did not take her own life and that the medical examiner’s office made a grave error in misclassifying her death as suicide. It is our hope that this litigation will not only result in the proper classification, but also brings to justice those responsible for her death.”

NJ Transit did not return a request for comment. The Attorney General’s office, which oversees the state medical examiner’s office, refused to comment.

A newly minted graduate herself, of Oakcrest High School, Valiante was heading to her cousin’s graduation party across the street when her mother last saw her in the driveway of their home in a wooded neighborhood off White Horse Pike.

“She was out by the car,” her mother Dianne Valiante remembered, of the last time she saw her daughter alive. “I walked inside to get my husband. I only left her for one minute. I walked back out, she wasn’t there.”

That was odd, considering it was dusk. The pair had squabbled briefly over a purchase Valiante had made on a friend’s credit card, but it wasn’t a big fight — and not enough to drive Valiante into the dark night, her mother said. Valiante was petrified of the dark and normally would never venture anywhere alone at night.

After her parents discovered she wasn’t at her cousin’s party, they began hunting for her, enlisting her two older sisters and Valiante’s uncle, a New Jersey state trooper, to help search. When her father Stephen found her cellphone dropped in leaves at the edge of the family’s property, the family panicked.

“Tiffany never went anywhere without her cellphone,” her mother said, adding that she even had a waterproof case so she could bring it into the shower.

At 11:30 p.m., two hours after her mother last saw her, the family reported her missing to police.

They didn’t know she’d already been dead 15 minutes by then.

A southbound train traveling 80 mph hit her, killing her instantly, on a dark, wooded stretch of the Atlantic City Rail Line in Galloway Township, nearly four miles from her home.

The family got the news at 2:30 a.m. Authorities told them Valiante had been hit by a train and died, but not that she’d committed suicide.

“When they first came to the house to tell us, I made them repeat themselves, because I just was in shock,” Dianne Valiante said. “They just said she was hit by a train. They didn’t tell us anything else … We thought she was in a car with someone, that (the car) got hit. That’s what we initially thought. We were like ‘Oh God, who else was in the car?’”

The next morning, they read in the local newspaper that investigators had deemed the incident a suicide.

“My husband called the paper up” to tell them that was wrong, Dianne Valiante said.

“Twelve hours later!” D’Amato added. “Is that a rush to judgment?”

Four days after Valiante died, investigators brought in a bloodhound, who traced her path from her house along the rocky, wooded edge of the tracks to the remote spot where she died.

But investigators couldn’t find Valiante’s shoes — nor explain their absence.

Dianne Valiante could.

In the days and weeks after her daughter died, she took to walking the roadways between her home and the train tracks. Walking offered comfort for her confusion and heartbreak.

And before long, walking offered up clues.

As she walked along Tilton Road a few weeks after the tragedy, something in the roadside weeds caught her eye: Her daughter’s shoes.

The beige slip-ons sat a few feet off the road, beside each other, as if she had doffed them intentionally. Beside them was Valiante’s headband.

The discovery was nowhere near the bloodhound’s trail and a mile or more from where Valiante was hit.

“Here is the essential and fundamental flaw of the investigation: They should have thrown out and disregarded the bloodhound, because it just doesn’t make any sense,” D’Amato said, adding that two storms dumped four inches of rain in the area — likely washing away scents — between Valiante’s death and the bloodhound’s visit. “Looking at Tiffany’s feet (from autopsy photos), they were as pristine as my little granddaughter’s feet. There’s no cuts, there’s no abrasions, there’s nothing.”

How, the family wondered, could Valiante walk barefoot for more than a mile over rocky terrain without injuring and dirtying her feet?

That’s key, agreed Louise Houseman, who was a senior medical investigator in the Atlantic County Medical Examiner’s Office before she retired in 2013.

One of Houseman’s children spotted Dianne Valiante during one of her many anguished walks and told her about it. Houseman then reached out to the family and offered to review the case pro bono.

In a 21-page report filed with D’Amato’s lawsuit, Houseman said there were so many “unanswered questions, false statements, conflicting accounts regarding this fatality, and incomplete investigative information” that the death ruling should be changed to “undetermined.”

“There is no reasonable explanation of how and why the sneakers Tiffany was wearing the night of her death were found — weeks later — more than a mile from the heavily wooded, dark, isolated location where she was struck by the train,” Houseman wrote in her report. “If she walked barefoot in those conditions, the autopsy of her feet would have showed lacerations, abrasions or indications of soil, grass, stone or gravel. No such evidence was detected.”

Houseman and D’Amato had other concerns, chiefly that investigators failed to:

- Interview Valiante’s relatives or friends, get her medical records and otherwise do a “psychological autopsy” to bolster or disprove their suicide theory.

- Test the train engineer — a student engineer who’d worked for the agency 14 months — for drug or alcohol intoxication. (They did test Valiante and found no intoxicants in her system.)

- Treat the collision site as a crime scene or look for tire tracks, weapons or other evidence of foul play. (The family found an ax and wooded encampment near the collision site, which they say investigators should have examined.)

- Do a rape kit on Valiante.

Some of that uncollected evidence will remain forever lost, because the family had Valiante cremated after her death.

“Worst decision of my life!” Dianne Valiante said, crying. “I just assumed they (investigators) did what they were supposed to do.”

Still, filing a lawsuit will help the family get answers, D’Amato said, because he can subpoena witnesses who may have seen Valiante in her last hour or so alive to testify under oath.

“When you look at everything that we have so far, you walk away and you say: ‘It wasn’t suicide,’” D’Amato said. “But then you just can’t stop there. You say: ‘OK, what happened?’”

Although it’s been two years since Valiante’s death, she still is very much a part of the family’s life.

They’ve built memorials for her just off the tracks where she was hit and at the site where her shoes were found. More shrines are at their home: A giant wooden T in the back yard, a regulation-size sand volleyball court in the side yard Stephen Valiante built after his daughter’s death, a glass case full of mementos in the living room. All brim with reminders of the things she loved: turtles and giraffes, the New England Patriots, softball, Great Adventure, the beach, and of course, volleyball.

Valiante had been offered five athletic scholarships to play volleyball in college, and she picked Mercy College in New York. She dreamed of eventually making the U.S. volleyball team to compete in the Olympics, her family said.

She wanted to study criminal justice, inspired by her state trooper uncle, and was considering a career in the U.S. Air Force, they said.

She had plenty of plans that would fill the rest of her summer before she left for college: An orthodontist appointment, a trip to Great Adventure, shopping for her dorm, and plans to get a kitten for her mother, who she worried would be lonely after she left for college.

One of her coaches will never believe Valiante killed herself.

“It’s just not the Tiffany I knew,” said Allison Walker, head women’s volleyball coach at Stockton University who coached Valiante in the East Coast Crush Volleyball Club, a junior travel volleyball team. “The time of night really didn’t sit right with me: Tiffany was deathly afraid of the dark, had to have the TV on if the room was dark. The thought of her choosing to walk through not just the dark, alone, but a dark wooded area, alone — never in my wildest dreams would that happen.”

Walker added: “I just want justice for Tiff, and justice for the family, who are just feeling as though they didn’t get all of the information. I would hope that at least they could get answers and information so that they could be at peace, one way or another.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.