Even with minimal anti-discrimination added, Indiana ‘religious freedom’ law still flawed

Some of the hundreds of people protesting against 'religious freedom' legislation signed last week by Gov. Mike Pence are shown standing on the Indiana Statehouse's south steps on March 28. (AP Photo/Rick Callahan)

Indiana’s “religious freedom” law is unique because it allows private parties to sue each other for interfering with the free exercise of religion. Until now, the intent of RFRAs has been protection from government interference.

For the last week, TV news, print news, social media, and conversations on the streets have been dominated by Indiana’s passage of its own state version of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA). If you haven’t heard about it, I hope that rock you’re living under is cool and mossy.

Reaction seems to have taken a few forms:

Outrage from various businesses, corporations, celebrities and other states over the bill and its potential effects.

Joy over the bill and its potential effects.

Wondering why Indiana deserves unique outrage when 19 other states have the same or similar laws.

This final category might have been inspired by articles like Hunter Schwarz’s in the Washington Post, “19 states that have ‘religious freedom’ laws like Indiana’s that no one is boycotting.” In fact, Pennsylvania has its own RFRA, enacted back in 2002. I wasn’t living in Pennsylvania in 2002, but my guess is the law was a spectacular non-event — free of protests, cancelled tour dates, and corporate hiring and expansion moratoria. I bet governors of other states didn’t ban official state travel into the commonwealth, and the Eagles coach did not write an open letter to the Inquirer condemning the law. (If I am wrong about any of this, please let me know.)

Why? Because it’s a different law. Back in February 2014, I wrote about federal- and state-level RFRAs (“Arizona dodges bullet with Brewer’s veto, but discriminatory ‘religious freedom’ sham continues elsewhere“), describing where the original idea came from, what it was meant to do, and what these state-level RFRAs can do if drafted the way that Arizona’s was.

RFRAs are good, but not this one

The most important part of this whole kerfuffle in Indiana surrounds a tiny bit of misinformation that Gov. Pence was peddling: the idea that the law is meant only to protect people from government interference in the free exercise of their religion. That bit of misinformation is insidious because, for the national RFRA and the vast majority of the state RFRAs, it’s completely true.

RFRAs are not bad laws and they did not come from a bad place. There is a reason that the original passed almost unanimously through both houses of Congress. The free exercise of religion was indeed being abrogated by the Supreme Court, and it needed protection. Where this went wrong was the idea that simply being around someone who believes something different from you, that not being able to stop someone from doing something you don’t believe in, is an abrogation of your free exercise of religion.

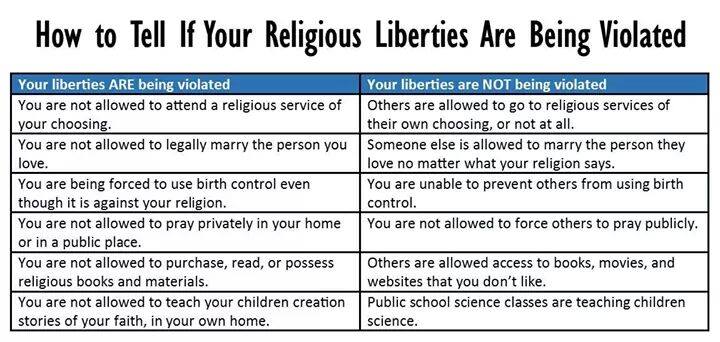

This little graphic has been floating around social media and explains what I mean admirably:

So why haven’t people been protesting these other RFRAs? And if the others aren’t a big deal, then why is Indiana’s? The key is in what Pence said. The law, as adopted in Indiana, does significantly more than just protect people from governmental interference.

As was the case with Arizona’s proposed RFRA, and with amendments that have been proposed to most of the RFRAs across the country (all of which have failed), the language of the bill itself tells us what the big deal is.

The difference between PA and AZ

Consider the Pennsylvania RFRA as representative of the majority of similar laws. It is actually called the Religious Freedom Protection Act. (It can be found in our Code at P.L. 1701, No. 2014.) Indiana’s law is called the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. It was enacted, though not yet added to the printed version of the Indiana Code. (You can find the version that was signed as Senate Enrolled Act No. 101.)

The important difference between the two laws is in the wording that outlines who can bring a claim against whom in court.

The Pennsylvania law only contemplates a claim against an “agency” of state or municipal government, while the Indiana law authorizes a claim without any limitation on who or what the claim can be brought against. It goes so far as to spell out that a claim can be brought, “regardless of whether the state or any other governmental entity is a party to the proceeding.”

Translation: Private parties can sue each other for interfering with the free exercise of religion, whether the interference is real or imagined.

That’s the real problem here.

There were two answers to the issue with Indiana’s RFRA — one simple and the other complicated and piecemeal. The easiest way to take the discriminatory teeth out of Indiana’s RFRA, and to return it to the original purpose for which it was intended, would be to change that little bit of the section that allows claims between private parties. Strangely, Indiana’s legislature and governor chose the more difficult path.

They inserted language clarifying that the law does not authorize a “provider” to deny service, facilities, or use of public accommodations to a person on the basis of race, color, religion, ancestry, age, national origin, disability, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, or United States military service. Of course, this clarification does not apply to churches, nonprofit religious organizations or schools, or any sort of rabbi or priest. Evidently, those people are still allowed to discriminate based on whatever they want.

But regardless of the breadth of the clarification language — and I cannot say this strongly enough — Indiana chose the wrong answer.

Yes, the changes will amount to a minimal bit of anti-discrimination law for LGBT citizens in Indiana, where none currently exists; however, that doesn’t address the larger issue.

In the end, RFRAs are meant to protect people’s constitutional right to free exercise of religion, not create a cause of action between two private citizens. Indiana’s RFRA is meant to reinforce the freedom of religion language in its Constitution; language that was adapted from the First Amendment. It says, “No law shall, in any case whatever, control the free exercise and enjoyment of religious opinions, or interfere with the rights of conscience.” The phrase “no law” means that the document is addressing the state and local government, not private citizens.

People — and I hope that everyone takes very, very careful note of this — have no express right under any constitution in the U.S., be it federal or state, to be free from exposure to objectionable speech or things that their religion frowns upon. That would contravene the entire point of a free society and the free exchange of ideas. The Indiana legislature and governor apparently disagree.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.