Lack of justice compounds pain and shame of abuse

Your Need to Feel Powerful Over my Small Body, by Jessie Hemmons

Childhood sexual abuse affects approximately one in every nine girls, one in every 53 boys, and 63,000 children in the United States every year. We all generally agree that abusers should be punished. But the thought of child abuse is so horrifying to many of us that we live in a state of denial about its existence right in front of our eyes — leaving victims like me feeling silenced and alone.

Victims of abuse often live in a world of other people’s emotions. People do not want to believe they could be friends with or related to someone who abuses children. This gut reaction is often what prevents us from achieving social justice (which may be the only justice available to us). I think people question the validity of abuse claims because it makes them uncomfortable to realize that they knew an abuser and weren’t aware of it.

‘No, I’m not okay now. Am I supposed to be?’

Additionally, there seems to be a limit on how long people can handle the victim’s emotional recovery. This is probably true for victims of all types of abuse. After a trauma occurs (and is substantiated), friends and family are quick to provide emotional support. But after a certain point, the tide begins to shift and the reactions start to resemble something like “It seems like maybe you’re beginning to let this control you” and “Are you going to let this event define you?”

I think people believe they are being supportive. Maybe they are worried their loved one is not doing well and may need additional help. But if their advice doesn’t address the real needs of the victim, it sounds more like: “I think I’m growing tired of hearing about your feelings, and I’d like you to get over it now.” This is what I mean when I say that victims live in a world of others’ emotions. At some point, the support begins to wane and the expectations begin, as though recovery from abuse follows a linear track and has a clear beginning and end.

My advice for loved ones is to think before they begin to ask these sorts of questions. Ask yourself, “Am I concerned about the welfare of my loved one, or does this have more to do with me and my feelings?” If you need a break from providing emotional support, let your loved one know you are there to support them, and you need some time for a little self-care. Let them know you aren’t abandoning them — instead, you want to regroup so you can be as supportive as possible.

An uphill battle for justice

But this is not the worst part. The worst part is trying to find justice for the crimes committed against us. For many victims of childhood sexual abuse, the evidence is scant and does not meet the threshold for a criminal arrest. Therefore, if the perpetrator is not a parent or guardian, little can be done to punish the abuser or prevent him or her from working in environments with children.

If the parent is the perpetrator, the battle is often fought in family court. If a victim’s protective caretaker cannot afford an attorney, he or she is left to navigate the legal system alone. If the caretaker of the child victim is a woman, gender bias and negative stereotypes create an additional uphill battle. Judicial committees around the country have assessed gender bias in family court and found that female caretakers are more susceptible to being portrayed as “hysterical” and “vindictive” in court. This can lead a judge to question the validity of the mother and child’s claim, even though several studies indicate the rate of false accusations of child sexual abuse is 5 percent or lower.

In addition to these biases, many women face allegations of “parental alienation” for trying to keep their child away from an abusive parent. Ironically, this can result in the protective parent actually losing custody of the child victim, who must return to the care of his or her abuser. The American Judges Foundation found that in approximately 70 percent of custody cases involving abuse, the abuser is awarded unsupervised joint or sole custody of the child victim.

To know this information is astonishing. To combat this horrifying reality, investigators and judges need to stop incorporating antiquated and statistically inaccurate stereotypes about women into their investigation of abuse and their assessment of the best interest of the child. When accusations of child abuse arise during custody hearings, both the protective parent and the accused abuser should receive legal counsel. Judges trained in handling claims of child abuse should be assigned to the case. If this requires a continuance, protective parents should be given the benefit of the doubt (due to the statistically low rate of false accusations) and awarded sole custody until the new hearing.

This reality helped inspire me to create the piece “Your Need to Feel Powerful Over my Small Body.” Beyond the layers of shame, guilt, and disgust that abuse leaves weighing heavily on every inch of my skin, the lack of justice leaves me feeling haunted forever. Knowing that the man who molested me is free roaming the streets, free to abuse other children, is what tortures me the most.

—

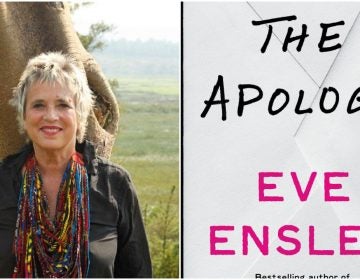

See work from Jessie Hemmons pictured above, and from eleven other artists — Aubrie Costello, Amberella, CALO, Homo Riot, Jesse Krimes, Joe Boruchow, Liora Ostroff, Michelle Angela Ortiz, Nether, Patrick Bowen, and Renda Writer — at Philadelphia Goddamn, Oct. 29 and 30 at Little Berlin in Kensington, Philadelphia.

Jessie Hemmons, known as ishknits, is a Philadelphia-based street artist who uses knitting and crochet as her medium. She has her Master’s degree in Clinical Psychology and integrates themes of mental health and advocacy into her artwork.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.