A tale of two Cubas, before and after Castro died

When Fidel Castro died on Nov. 26, I was in Cuba on a cultural exchange with my school. I had the unexpected opportunity to experience the national mood both before and after the loss of its revolutionary dictator. I witnessed the island nation, slightly smaller in size than Pennsylvania, go from one extreme to another.

I arrived on Nov. 18 and spent my first week touring the towns of Trinidad and Cienfuegos, I swam in the Bay of Pigs, and eventually I ended up in Havana. In the major cities, I saw music and dancing around every corner. The lively atmosphere was filled with rhumba and salsa rhythms.

Each city offered a completely different experience, but the overall atmosphere stayed constant throughout the first part of the trip. Every person we met greeted us and asked us where we were from, because seeing a large group of 20 American high school students was out of the ordinary. We were considered foreigners in the Cuban communities we visited. We were different, but they welcomed us. The excitement on the faces of the locals when we said “Somos de Estados Unidos” (We are from the United States) was incomparable.

Castro died while I was in Havana, and the mood of the entire country changed overnight.

When I woke up the morning of Nov. 27, it seemed as if the country had hit the pause button. After eating breakfast, I was dazed and confused, to say the least. Communication there, with spotty cell phone and wifi service, is not what I am used to in the United States. When I heard the news, I immediately asked our casa particular host, Jorge, what he had to say. I have trouble understanding his response, because his English vocabulary (and my Spanish vocabulary) was limited, and he had a thick Cuban accent.

His reaction to Castro’s death was simple: “It is a sad day in Cuba, not in Miami.” Jorge was born a decade after Castro’s revolution ended in 1959. When I asked him how he personally felt, he said something along the lines of “I do not feel strongly for either side. I wasn’t born when [Castro] was leading the revolution.”

I then asked him, to the best of my ability, what will happen next. Jokingly he said, “They’ll eventually build a monument, but first there are nine days of mourning that has to occur.”

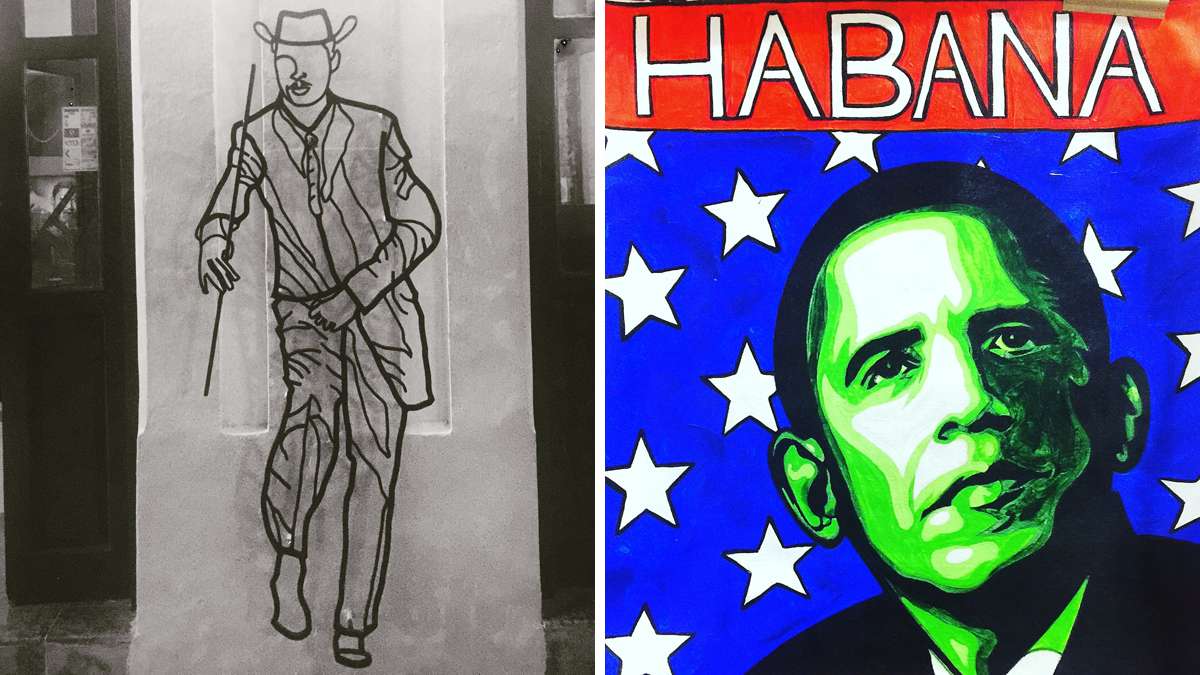

On the first day of mourning, I had to do what every American does traveling abroad: exchange money. The cash exchange was a hotel in a square that the locals called “Pigeon Square,” but which is formally called Plaza San Francisco de Asis. In the days preceding Castro’s death, the plaza was busy and filled with tourists thanks to the cathedral there and the bronze statue of José María López Lledín, a famous 20th century street personality. But after Castro passed, not even a pigeon was to be found in the plaza. During my final two days in Havana, this was a common sight. No one was allowed to sing or dance or even play music. The atmosphere was somber and tranquil. The nine-day mourning period wasn’t enforced by anyone. It was simply something everyone agreed to do.

On the afternoon of the 27th, we visited a local school in central Havana. The school’s primary focus was to use art as a means of education for boys and girls. When we arrived, the children were excited. They had prepared some poems and drawings for us. While one of the students was introducing himself, he said that he loved to sing. He asked his teacher if he could sing one of the songs that he and his classmates knew. The teacher explained to us how they really weren’t supposed to be doing this, so it had to be cut short, but she didn’t want to dampen the child’s enthusiasm to show visitors his prolific talent.

After his song, I did my best to talk to him in Spanish. My question was simple and to the point: How do you feel right now, as a 12-year-old boy, in Havana. Standing at about my waist, he looked up and said in a mix of English and Spanish, “Mi abuela feels sad, mi madre feels happy, and I feel okay.”

This 12-year-old boy had just encapsulated how the Cuban people feel about Fidel Castro. Even though he didn’t know if I understood, I realized that the response to the dictator’s death is generational. Sometimes kids have the ability to sum up complicated concepts in one sentence, and that is what the boy did for me.

—

Sam Gerlach, a senior at Springside Chestnut Hill Academy, loves to travel. He has spent much of his life exploring different cultures, from a 7th grade trip to Rome, to a 9th grade trip to Ethiopia, to his latest travels in Cuba. “Immersing myself in other cultures is how I get away from the craziness in America,” says Gerlach.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.