En South Philly, three immigrant mothers came together to form una ‘bonita familia’

Women account for a growing share of Latin American immigrants settling in the U.S. In Philly, three mothers share resources to thrive in their new home.

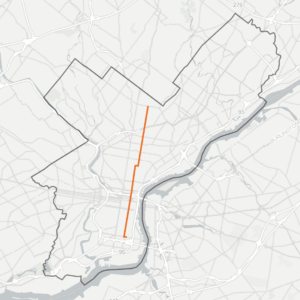

This story is part of The 47: Historias along a bus route, a collaboration between WHYY’s PlanPhilly, Emma Restrepo and Jane M. Von Bergen.

This article is written in a combination of English and Spanish. To read entirely in English, click or tap here o para leer en español, haga clic o toque aquí.

When Marta Caj was running late, she’d grab the Route 47 bus to her job at Las Amigos Bakery in South Philadelphia.

The bus is steady, reliable — an urban workhorse that moved 16,299 people a day, pre-pandemic, on its 10-mile route linking Latino neighborhoods in North and South Philadelphia.

It’s nothing like the buses that Marta encountered traveling with her daughter, then five, on their three-month journey north from Guatemala in the summer of 2019. At one point, Mexican officers boarded the bus and asked for documents. The two people Marta was traveling with had to leave.

As she and her daughter sat in the third seat, the officers stood right in front of them, but didn’t ask her anything.

“Viajábamos en el mismo autobús, pero los federales nos pararon y nos pidieron documentos, pero no me preguntaron nada. Yo estaba en el tercer asiento con mi hija. Y no lo veo como una obra del azar sino como una obra de Dios porque ellos también se pararon frente a mí”, dijo Marta.

These days, Marta lives closer to her job, within a short walk. In her new home on Wolf Street, she shares resources and child care with two other women, one from Guatemala and one from Honduras. Their last names are being withheld to protect their privacy. Marta and Sandra, who both work, live together and pay the third, Jaime, who lives nearby, to care for their children and hers. They cook for each other, talk about their days and celebrate special moments. They are family.

“Cuando es el cumpleaños de la otra compañera, lo celebramos. Así es una convivencia muy bonita y una amistad”, dijo Marta.

On her way to the bakery, Marta passes Route 47 bus stops while crossing Seventh and Eighth Streets. More than a third of her neighbors take public transit to work: The bus is a neighborhood fixture, almost a friend.

But in Mexico, as she was heading north in the summer of 2019, the bus trip was hardly friendly. A gang stopped the vehicle, beat the driver, and pointed guns at the passengers, forcing them to kneel outside. They demanded their money. The criminals took them to a place they did not know and released Marta and her daughter, along with the others. Her daughter, Krishna, now six, is still affected by what she saw on the trip.

“Mi niña en todo ese viaje despertó. Ella ya no se comporta como una niña. Su mentalidad es diferente. Ella habla como una niña de doce o trece años. Le cambió la vida psicológicamente. Vio cosas que no debió de haber visto. Ella piensa como alguien maduro”, dijo Marta.

Guatemalans, Hondurans and El Salvadorians constitute a growing proportion of migrants crossing southwestern borders, outpacing Mexicans. In 2019, when Marta was headed north, the U.S. Customs and Border Protection office recorded 264,168 migrants from Guatemala compared to 166,458 from Mexico.

Corruption, lack of jobs, loss of crops due to climate change and violence —including domestic violence — are among the factors motivating women to leave their home countries. And when they do, they face risks men don’t face on what has become an increasingly perilous journey.

Like Marta, more women are taking the risk. About 25% of migrants taken into U.S. custody at the Mexican border are women, up from 13% in 2012. In 2017, one in three children stopped at the U.S./Mexican border were girls under 18 from Guatemala, Honduras, or El Salvador – girls like Krishna.

Marta faced many hardships on her journey, but along the way, there were also moments of kindness and luck. A Honduran man cared for her when she was sick, bringing food. After a grueling experience crossing Rio Grande and carrying Krishna on her back as she ran toward safety, Marta was detained in Texas where she found a lawyer who helped her win a case for immigration based on fleeing domestic abuse.

In Philadelphia, the brother of a hometown friend paid for airplane tickets so Marta and Krishna could come live with his family while she searched for work.

“Todo lo que me pasó Dios ya lo tenía que eso iba a ser así. Mi camino iba a ser duro para que yo entendiera el valor de las cosas”, dijo.

While job-hunting, Marta spotted a ‘help wanted’ sign in the Los Amigos bakery window on Ninth Street. She told the owner that she didn’t know English or baking, but promised to learn. He called three days later. She started to work that day.

“Así fue como llegué a esta bendita panadería donde he conocido mucha gente, es mi primer trabajo y yo siempre lo llevaré en mi corazón”, dijo Marta.

She soon met the other two women who would become her Philadelphia family and a beautiful friendship began.

“Y ahí fue en donde entre las tres empezamos a llevar una amistad muy bonita”, dijo.

The three women have four children altogether. There’s Marta’s daughter along with Sandra’s son David, 6, and Jaimi’s two boys, David, 7, and Jose, just a few months old.

“Es muy bonita porque nos ayudamos entre las tres. Compramos comida entre las tres. Hay días de descanso y los usamos para comprar despensa. Cuando yo no tengo, la otra tiene y cuando la otra no tiene, yo tengo”, dijo Marta.

The bakery owner, her other friends, and her housemates – she’s grateful to them all.

“Y esas personas llegan a tu vida sin conocerte y te tratan bien. No son de tu propia sangre, pero están ahí, están ahí siempre”, dijo.

In Guatemala, Marta worked from 6 in the morning until 11 at night, sometimes longer, selling fruit to feed her daughter and two sons “because with your own business, a day you don’t work is a day you don’t eat.” Marta wanted more for her children.

In Philadelphia, she appreciates an economy that allows her to work eight or nine hours a day instead of 15 — and a local culture that she describes as “polite” and law-abiding.

“En primer lugar, fuentes de trabajo. Aquí trabajas lo normal, nueve u ocho horas. Cosa que en nuestro país no hacemos. Sobre todo la gente es muy educada. Más que todo en los carros. Si vas pasando hay un gran respeto, paran, es una cultura demasiado diferente. Aquí sí hay leyes, aquí sí se respeta, aquí se aplican los principios y valores”, Marta dijo.

The children too have a better life. Even though Marta thinks American parents overprotect their children, young people have a chance to get an education here and don’t have to work, as her sons did, when they helped her sell fruit.

Marta has no regrets about building her life in Philadelphia, yet it has come at a heartbreaking cost. She had to leave her two sons behind. Now 15 and 12, they live with her grandmother. Marta sends money and talks to them often. They’ve been earning good grades, pointing to a brighter future.

“Me doy cuenta que el sacrificio no fue en vano. Quizás no les podía dar cosas que les puedo dar ahora. Quizás ahora tienen cosas materiales, pero yo no puedo estar con ellos”, dijo.

And it’s painful.

“Hay momentos en que estoy en un lugar comiendo y dejo de comer. El estar lejos de los hijos es lo peor que puede haber. Nunca tienes paz; te levantas pensando si comieron, si están bien, si llegan a la casa. Y tú llegas y es un país de soledad. Más que todo de soledad, de cosas materiales; no hay nada como llegar y abrazar a tus hijos”, Marta dijo.

In her loneliest days here, Caj longs to hold her sons in her arms. She is their mother.

WHYY is one of over 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push towards economic justice. Follow us at @BrokeInPhilly.

WHYY is one of over 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push towards economic justice. Follow us at @BrokeInPhilly.

Subscribe to PlanPhilly

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.