Empathy experiment takes doctors, students out of the ‘surgical theater’ and into the actual theater

Listen

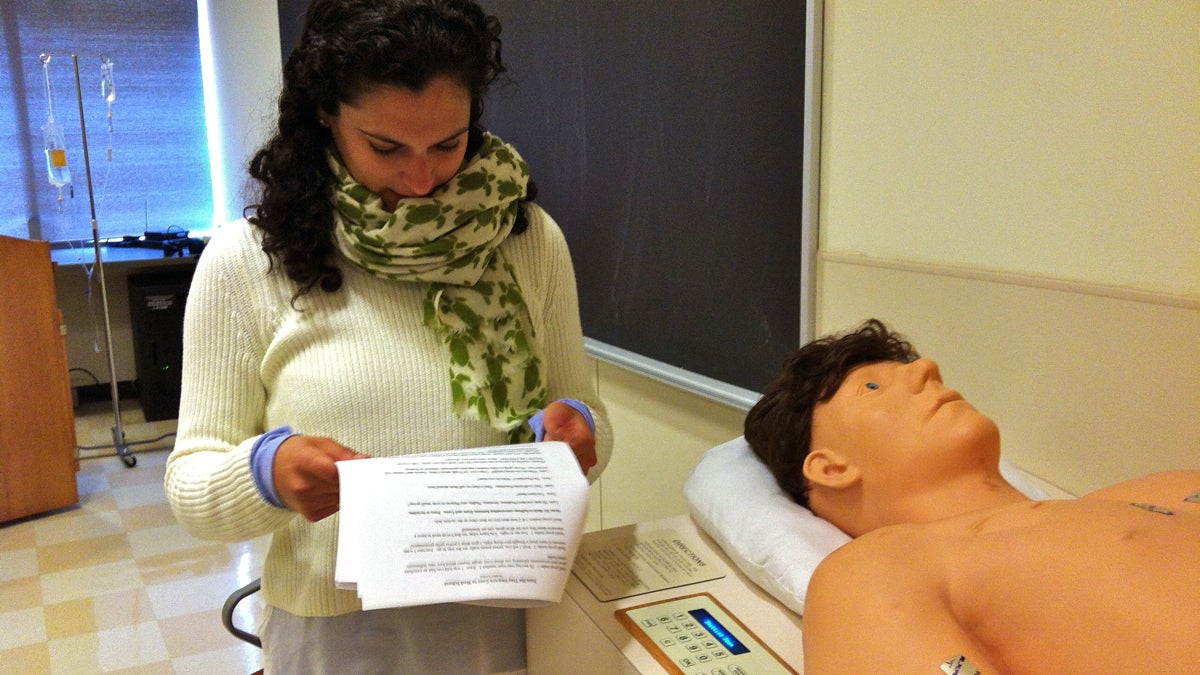

Second year medical student Yasmine Koukaz reads from a play she wrote in theater class. It's called "Zuzu the Tiny Unicorn Goes to Med School." One of the characters in her play (and others) happens to be "Harvey," this patient simulator normally used to help students learn about the heart and lungs. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

An invisible unicorn goes to medical school and lives in a syringe.

A doctor grapples with knowing privately disclosed information from a recently deceased patient that could impact the family.

A cadaver reflects with “Death” about donating his body to science as confused students dissect him.

A new doctor oversees the care of a sick patient and it’s messier than expected.

These are some of the plots developed by students and health professionals in a rather unusual 15 week experiment.

The laboratory? The stage (ok, in reality, the third floor of Jefferson’s Hamilton building).

The hypothesis: could theater inoculate soon-to-be medical providers against losing their empathy, their sanity, and prevent burnout and poor patient care?

‘Background’

Burnout is a major problem in health care, according to Dr. Sal Mangione, a professor of physical diagnosis at Thomas Jefferson University’s Sidney Kimmel Medical College and head of the school’s humanities program. He sees a lot of soon-to-be doctors lose something along the way: their empathy, and even worse, a part of themselves.

“We are the profession with the highest suicide rate,” he says. “Clearly something breaks. On the other hand, if you ask why and what, that becomes more difficult.”

Mangione has a theory that this burnout is in part because being human is messy. Situations in that exam room aren’t black and white, even though a culture pervades medical training that demands clear answers. He worries that’s cheating students and health professionals of important skills, dealing with “the grey,” the “ambiguity,” and the full spectrum of being human.

And yet it’s those same individuals who have a front row seat to pain, suffering, and other realities of being human.

“It’s almost ironic that people who are seeing the human condition at its worst have no tools to metabolize what that means,” says Mangione.

Theater, on the otherhand, often serves as a space that embraces that ambiguity, exploring the realities of what it means to be human, and helps foster empathy through the development of characters.

“One of the purposes of theater is to be a place where you can face your fears or face your inadequacies, and you can wrestle with the questions of what kind of world you want to be in and who are you in that world,” says Kittson Oneill, an actor and dramaturge with Lantern Theater Company, located blocks away from Jefferson.

Mangione, a self-described theater fanatic, got to thinking about this and then connected with Lantern after attending a performance.

With support from a grant, Mangione, Oneill and others from Lantern then embarked on a rather unusual two-year pilot, beginning in the fall of 2014.

The hope was to examine whether creative outlets like theater could build up and protect those parts of the brain and soul that get damaged during training and even later in practice, that then lead to burnout and a loss of empathy.

‘Method’

The design of this study was a 15-week theater course meeting 2.5 hours a week, geared toward students and health professionals.

The class began with some theater excercises but quickly moved into writing prompts and a focus on developing and sharing plays with one another.

Twenty-seven subjects signed up, mostly medical students but a few doctors and other health professionals as well. It was a self-selecting crew, as the program was voluntary. They were broken into two groups.

Participants took surveys before and after the course. Mangione, with the help of a colleague, plans to evaluate that feedback, track whether the experience might have any impact, and further measure participants’ empathy.

‘Results’

The course produced 27 plays (about 10 minutes or less in length) exploring everything from the stress of school to ethical quandaries of patient privacy.

A public reading of selected plays by Lantern actors is slated for Sunday, May 3, at 2 p.m. at Jefferson’s College Building at 1025 Walnut street.

‘Discussion’

Oneill and Craig Getting, an artistic associate at Lantern, started the course with some basic theater exercises.

It was awkward at first.

“We had to say our name and at the same time strike a pose,” recalls Dr. Katherine Sherif, director of Jefferson Women’s Primary Care. “And I really, reaaaally didn’t want to do that.”

Getting and Oneill were surprised to observe during character-portrayal activities, where students were to mimic the walk of someone in the real world, many were quick to diagnose one another.

“Someone would bring in the slow, shuffling walk, and we would see the long life…their sadness. And the students were like, ‘Oh, I wonder if that’s a neurological effect,'” she recalls. “It was a different eye on things.”

The initial discomfort also quickly faded, with Sherif reporting she and others were able to relax “in the company of peers.”

Anecdotaly for some participants, the experience was therapeutic.

“We talked about faith in medicine in one person’s story, we talked about loss, really nothing was off the table,” says first year medical student Katheryn Linder. “At least so far in first year curriculum, we really don’t have a platform for that, there’s no avenue for that.”

Sheriff wrote a series of comedic vignettes based on some fumbles early on in her career, that she’d never talked about before.

“We rarely sit down together and talk about what we do,” she says, referring to the community space created through the class. “I think that would be very healing. I think that would help with the cynicism.”

Another major component of the play-writing process involved exploring the full dimensions of all characters.

“Many of these writers were sharing very personal stories and they were giving characters in plays that were not based on them short shrift, kind of judging the other characters in these plays that were not based on them,” says Getting. “And a lot of our work was making them realize that bias and asking them to explore the other side of that story.”

“Just the pure act of making a play forces you to think empathetically from the point of view of someone who is different from you,” adds Oneill.

That point resonated with second year, Yasmine Koukaz.

“It gave me a new perspective on how to see people, both patients and just day to day,” says Koukaz. “And I think that will percolate into patient care each and every day when that happens.”

‘Conclusion’

Pending. Another ‘trial’ is slated for next year.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.