Election upgrades could come with hidden costs for Pa. taxpayers

Already facing $100M+ in upfront costs for machines, counties are struggling to pin vendors down on pricing for software updates.

Centre County introduced new ES&S voting machines in the primary on May 21, 2019. (Min Xian/WPSU)

This article originally appeared on PA Post.

—

Pennsylvania taxpayers could be on the hook for costs to update voting system software — future expenses above and beyond the estimated $150 million for new machines that almost all counties must have in place by the next primary.

At issue is who will pay for certain software and security upgrades. Whether counties, voting machine companies or both will pay, those changes are hard to predict. They also could require significant work to implement across thousands of machines.

“I don’t think (the companies) would be in business very long if they agreed to cover everything,” said York County’s Director of Technology Joe Sassano. “We are just trying to constrain it. You don’t know what’s going to come down the line.”

The state’s bulk-purchase agreement attempts to limit future upgrade costs by requiring vendors to wrap costs for possible software modifications into their prices. But not all counties bid on new machines through COSTARS, as the state’s program is known. That’s partly because some were already far down the road to replace their aging voting machines by the time the state finalized its terms.

“Some of the counties were working off the contract language that they had already been negotiating,” said Doug Hill, who heads the County Commissioners Association of Pennsylvania.

Windows 7 operating system and related supports, for instance, will expire soon. Many machines rely on the outdated OS — even those being sold right now in Pennsylvania and other states, the Associated Press found recently.

Some Pennsylvania counties’ contracts already put the financial onus on vendors for updates related specifically to the Windows 7 issue. The Department of State says COSTARS counties won’t have to pay to address it.

But that doesn’t cover every county, nor other scenarios that might require a patch, update or upgrade. DoS also maintains that COSTARS counties won’t incur any expenses for vendors to address similar situations, standing by that claim even after PA Post relayed some counties’ contradicting understanding and pointed to fine print in contracts that tells a different story.

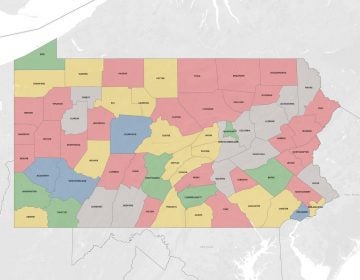

Ultimately, taxpayers’ exposure depends on where they live, the voting machine vendor their county commissioners picked, and the details of each contract, according to PA Post’s review of contracts.

One universal factor complicating cost control for counties is certification, the government’s process for approving voting machines for official use. In Pennsylvania, that costs between $60,000 and $80,000 (midrange, according to vendors). It’s another $1 million for federal certification. Each takes months to complete. Not every patch, upgrade or update would require recertification — but some will or might, according to Hill.

Moving the needle?

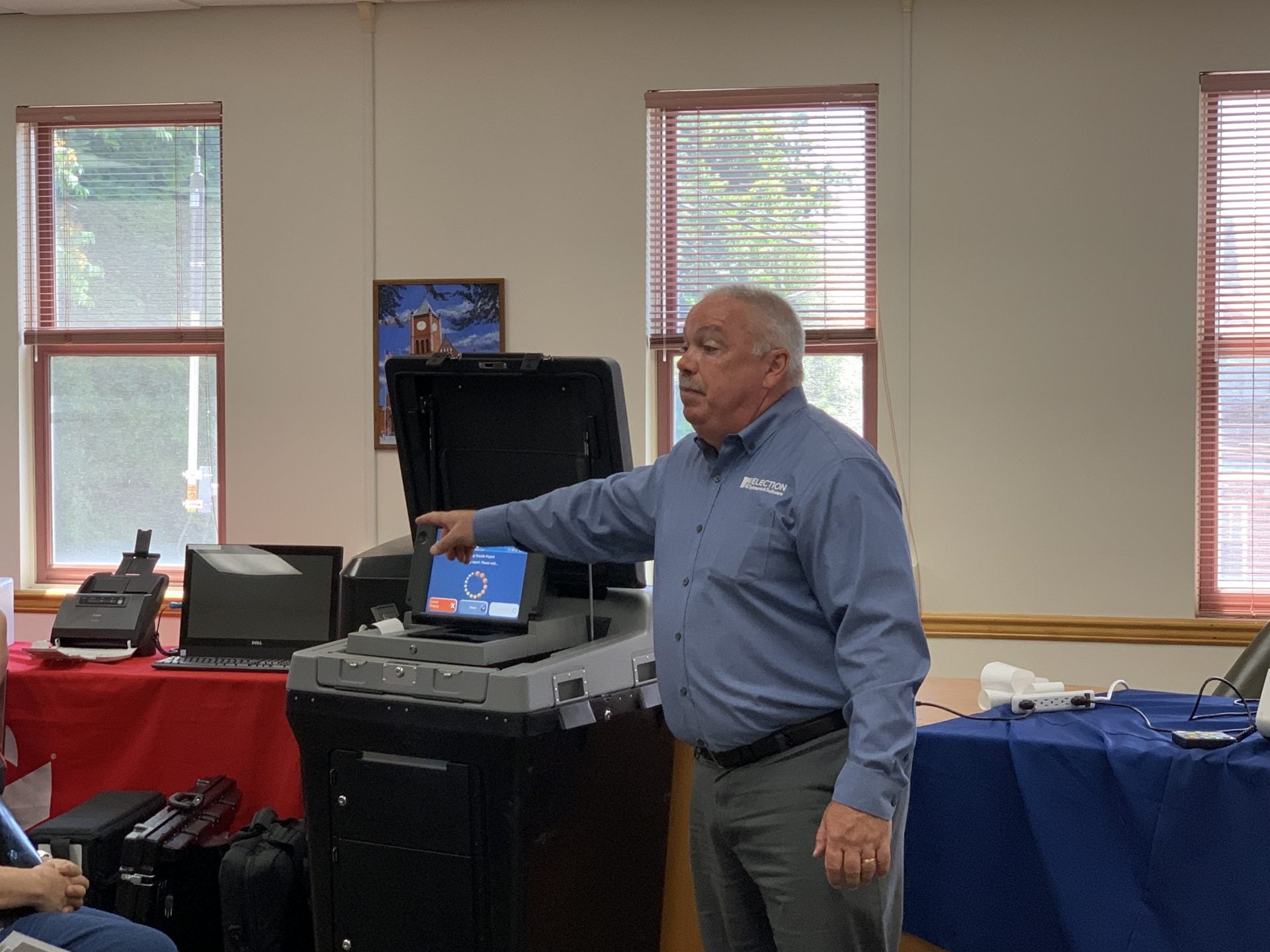

Officials in Venango County finalized a voting machine contract June 11 with Election Systems & Software (ES&S). The industry giant, a 450-employee company based in Omaha, Neb., has won the lion’s share of more than 30contracts awarded so far in Pennsylvania.

Venango’s agreement specifies that ES&S will make an exception to its rule of charging customers for patches, updates and upgrades with respect to anything Windows 7-related. In other such situations prompted by a change in state law, Venango would pay a share of costs prorated by its percentage of registered voters from all Pa. counties that are ES&S customers, according to the contract.

As of this week, ES&S has contracts in 25 counties home to more than 3.2 million voters. Nearly 30,600 of those voters — less than 1 percent — live in Venango, according to the latest Department of State registration statistics. So, if ES&S incurs $1 million in research & development costs to address a change in Pennsylvania law, then Venango would owe just under $10,000.

Prorated cost-sharing for such software updates appears in every agreement provided to PA Post that involves ES&S.

“It wasn’t significant in choosing the vendor,” said Venango Solicitor Richard Winkler of language concerning updates, “but it was in bringing the contract together.”

Winkler and officials from other counties — including Blair, Centre and Franklin — say their understanding is that they won’t pay for patches or other changes related to Windows 7, but that anything else could mean additional expenses. That was the line from counties, regardless of whether they bid through the state contract (COSTARS terms include requiring software update costs to be built into pricing).

Eddie Perez, global director of technology development at the nonprofit Open Source Election Technology Institute, says counties should strive for as much specificity as possible.

In Beaver County, the contract goes into even more detail in a page-long memo dedicated to the Windows 7 patch, making it clear the county won’t have to pay.

That’s unusual, said Perez, formerly director of product management at Hart InterCivic (another company certified in Pennsylvania).

Beaver County officials say they stood firm on getting it in writing that they won’t have to pay; ES&S declined to confirm.

“Every county should be saying to their vendor, ‘Give me assurances like this’, … and put it in the contract. It’s becoming such an issue of concern that it should be included,” Perez said. “It would be a very good way for counties to protect themselves and if everybody started doing that sort of thing, if all vendors held accountable for upgrades at that level of detail, it would be moving the needle forward compared to what’s normal for the industry.”

‘It’s not that straightforward.’

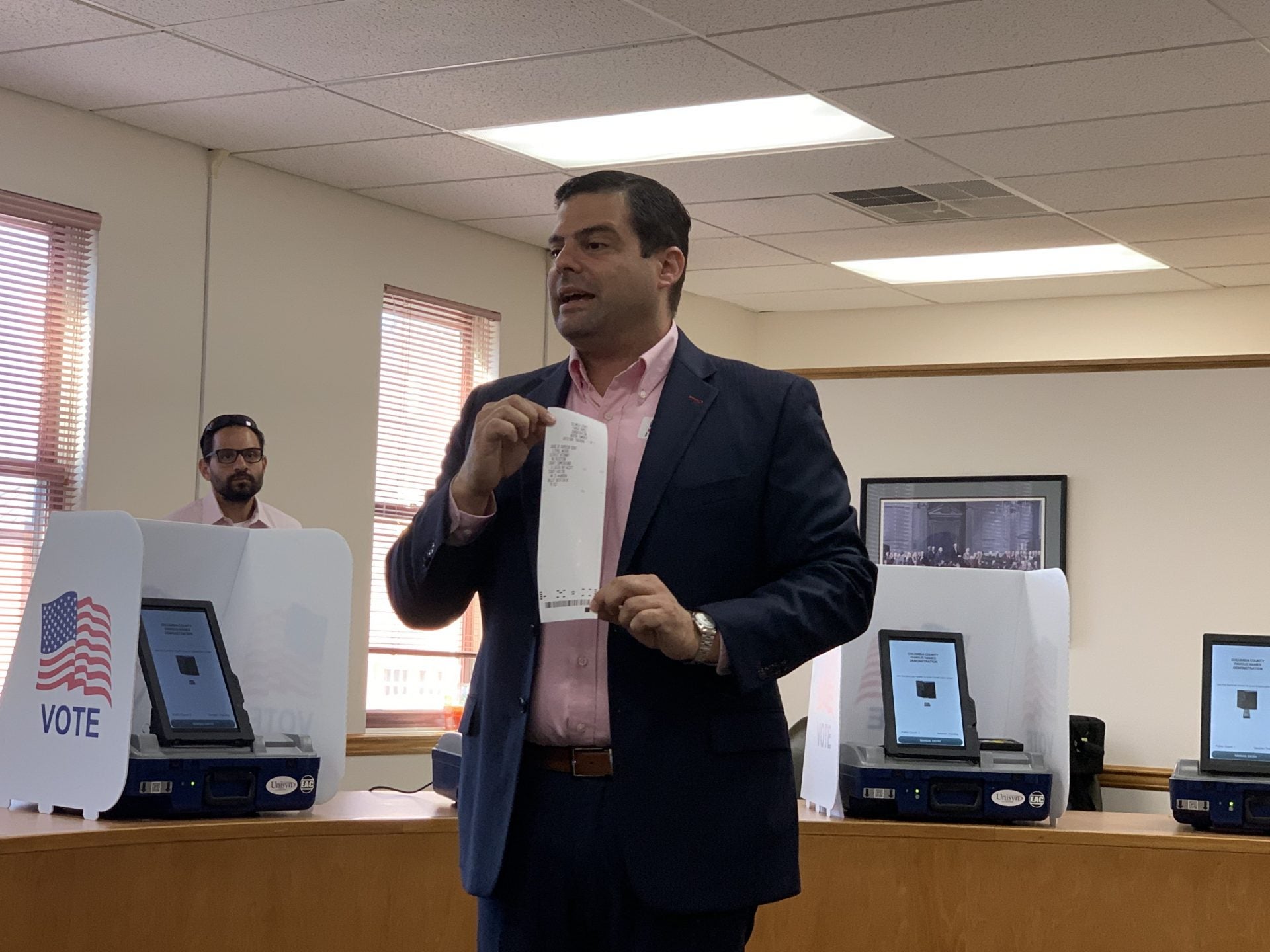

Representatives from ClearBallot and Unisyn/ElectionIQ say the companies will cover everything; however, their contracts aren’t as explicit.

“Don’t simply trust a vendor that says, ‘This will be covered,’” Perez said. “It’s not that straightforward.”

Unisyn’s system runs on Linux, not Windows. Using a system built on the open-source software should offer counties some protection from problems like replacing a program like Windows 7 that is no longer being supported by its creator, according to ElectionIQ vice-president Dan Chalupsky.

The pledged full coverage for other patches, updates or upgrades — stemming from a change in state requirements or otherwise — isn’t spelled out in contracts because “it’s a standard Unisyn policy, nationwide,” he said.

“The county … shouldn’t be penalized, just because someone else decides to make a decision that would require an upgrade,” he explained. “So, it’s a cost of doing business.”

So far, three counties have gone with Unisyn/ElectionIQ. Four have gone with ClearBallot. Those agreements also don’t delve into handling updates.

Sara May-Silfee, director of elections and voter registration in Monroe County, says the yearly maintenance fee included in its new contract increased significantly — from $16,000 to $44,000 a year.

“That was 13 years ago. And because of heightened security (concerns), it increased potential to have to make a change,” May-Silfee said. “Every time you go back to the state, you have to pay and it’s big money. That’s why, with the (last voting) system, … hardly anyone did any updates because it’s so expensive.”

The $44,000 annual fee, however, is in line with what other counties are paying, regardless of the vendor and understanding of what’s covered.

Wyoming County officials say their understanding of what to expect with ClearBallot was significant in the county’s switch from ES&S. The county had been in business with ES&S for two decades, according to county Director of Elections Florence Kellett.

“We were nickeled and dimed to death,” Kellett said.

Counties need to read the fine print to avoid being baited with better up-front pricing in exchange for negotiating outside COSTARS terms, she said.

“I assume it’s the same with other companies, not just ES&S,” she said. “We went to great lengths to ensure our contract with ClearBallot was in line with what COSTARS said.”

Unknowns abound

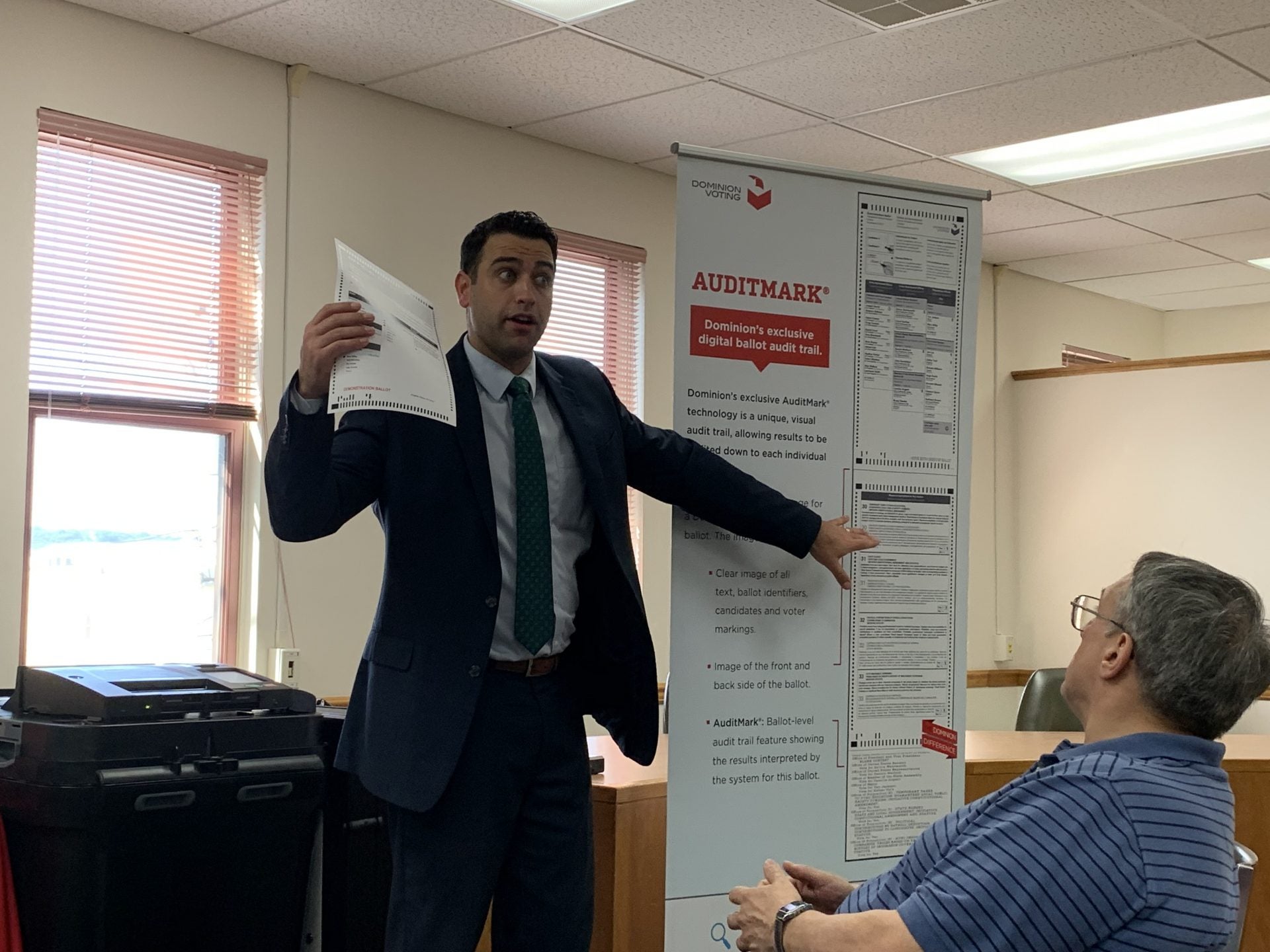

Dominion Voting Systems’ agreements also are vague when it comes to patches, upgrades and updates.

In Crawford County, it contributed to the county’s decision to lease instead of making an outright purchase, according to Chief Clerk Gina Chatfield.

“Until you know what you’re facing, you can’t define terms around it,” Chatfield said. “But, it’s in our contract that if any other county is afforded a deal on an upgrade or whatever, that does roll back to Crawford.”

Crawford, one of five counties going with the Toronto-based corporation, also didn’t go through COSTARS.

Montgomery County didn’t either, but did buy the machines, and rolled them out last spring.

Officials there, however, have not yet been able to point to the place in the contract stating clearly what would happen in the event a security patch, or an upgrade stemming from a change in state law or otherwise is necessary.

Dominion spokeswoman Kay Stimson says their machines run on Windows 10, so that won’t be an issue. Other patches, updates and upgrades are typically done at the company’s cost, Stimson said. She didn’t respond to requests for examples of scenarios that might fall outside the usual parameters.

But, the issue of security patches (related to Windows 7, specifically) extended negotiations to finalize York’s contract with Dominion, according to Sassano.

“The county is hopeful that the state will provide further guidance in the near future regarding how vendors are to get those upgrades approved for use by the state and to the counties quickly,” said spokesman Mark Walters via email. “But without that guidance, we believed it necessary to more specifically negotiate those provisions to protect York County residents from any additional expense or delay related to upgrades.”

Bid through COSTARS, the agreement York ended up getting doesn’t mention Windows 7 specifically, though. And its sections on updates during and after the initial term refer to each other and don’t make it clear what will happen in that scenario. County officials were unable to clarify.

Some counties are opting to do their own thing because they can get a better deal despite economies of scale and factors in the state’s favor, according to Dave Witchey, Columbia County chief clerk.

“These companies want the business,” Witchey said. “They know their profit margins. They might give up a couple points to get the sale.”

Columbia held one round of vendor presentations and scheduled the next for mid-August.

Security patches and any upgrades or updates that might be warranted in the future — and how much they’d cost — are among the many factors that could influence pricing and negotiations. They’re not top of mind at this stage, however, Witchey said.

As for the estimated cost range of potential patches or upgrades?

Winkler said he’s not sure what Venango would face.

Sassano also couldn’t estimate York’s potential exposure.

In fact, none of the counties nor the state nor any voting machine vendors could — or would — give a range or estimate.

And, as CCAP Executive Director Doug Hill said, not every software update will warrant recertification.

There also are expenses entailed in developing and deploying patches and updates apart from certification.

But certification timelines are a problem, leaving technology dated by the time it gets through the process, Perez said.

“Until changes happen that allow more rapid upgrades to be possible,” he said, “it is probably the case counties will be lagging behind tech developments to some degree.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.