Economic investment, not arrests, will save Kensington from drug violence, say researchers who lived there

They wanted to know: Why is narcotics trafficking and the violence that goes along with it so concentrated and so extreme in this part of the city?

Listen 2:23

Kensington from above (Max Marin/Billy Penn)

The sun had just set on a block in the heart of Kensington’s open-air drug market, where anthropologist Philippe Bourgois was recording an interview, when he heard a barrage of voices demanding that he drop to the ground.

“I thought we were being mugged,” said Bourgois. “Everyone else threw themselves on the ground, put their hands behind their backs, and was handcuffed.”

Bourgois didn’t realize he was part of a sweeping arrest conducted by plainclothes members of the Philadelphia Police narcotics squad. But his neighbors and friends and the person he was interviewing all knew the drill.

“They simply arrested every single human being that was outside and walking around in that moment,” he said.

Over time, Bourgois got used to the routine, too. That’s because he and three other researchers rented an apartment — two of them living there full time for six years, from 2007 until 2013 — in one of Philadelphia’s poorest, most violent, and most heavily policed census tracts. The results of that research are in a new study published in the academic journal Plos One.

The anthropologists wanted to know: Why was narcotics trafficking and the violence that goes along with it so concentrated and so extreme in this part of the city?

Their conclusion — that economic disinvestment left this majority-Puerto Rican neighborhood vulnerable to the impacts of the drug trade and the violence that comes with it — was not groundbreaking in and of itself. But much of the previous research on Kensington has focused instead on the population of people who use drugs, with a mind toward curbing opioid overdoses.

Joe Friedman, an M.D./Ph.D candidate at UCLA who co-authored the study and did statistical analysis for it, said that if we also want to treat violence as a public health issue, we have to look at the structures that produce it.

“We can’t just focus on the victims of violence, or just focus on people who are using drugs,” Friedman said. “We also have to focus on the people who are heavily incentivized to sell drugs, have very few other options, and then as part of doing that, violence is just the natural, logical thing that’s baked into the system.”

Bourgois, now the chair of the Department of Anthropology, History and Social Medicine at UCLA, was a professor at the University of Pennsylvania at the time. His wife, Laurie Kain Hart, at the time a professor at Haverford College, assisted with the research. Two other researchers, George Karandinos and Fernando Montero Castrillo, were undergraduates at the time of the study and were the ones living in the apartment full time. All the researchers are white except for Montero Castrillo, who is Latino.

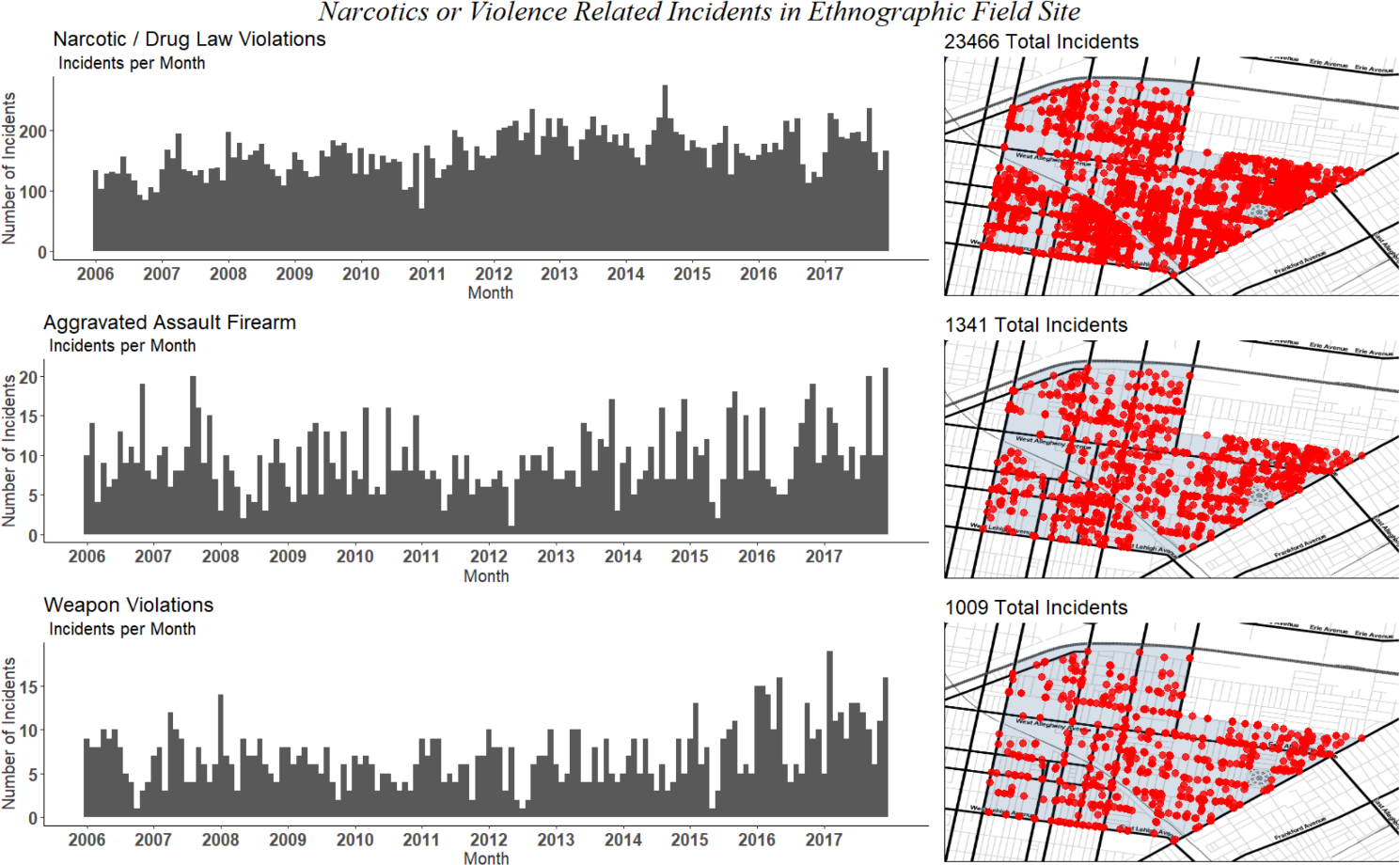

Shown by monthly incidence (left) and spatial distribution (right). (Plos One)

During their six-year stay in Kensington, the researchers immersed themselves in the neighborhood, doing what ethnographers call “participant observation” interviews. They collected hundreds of hours of recorded interviews with dozens of people.

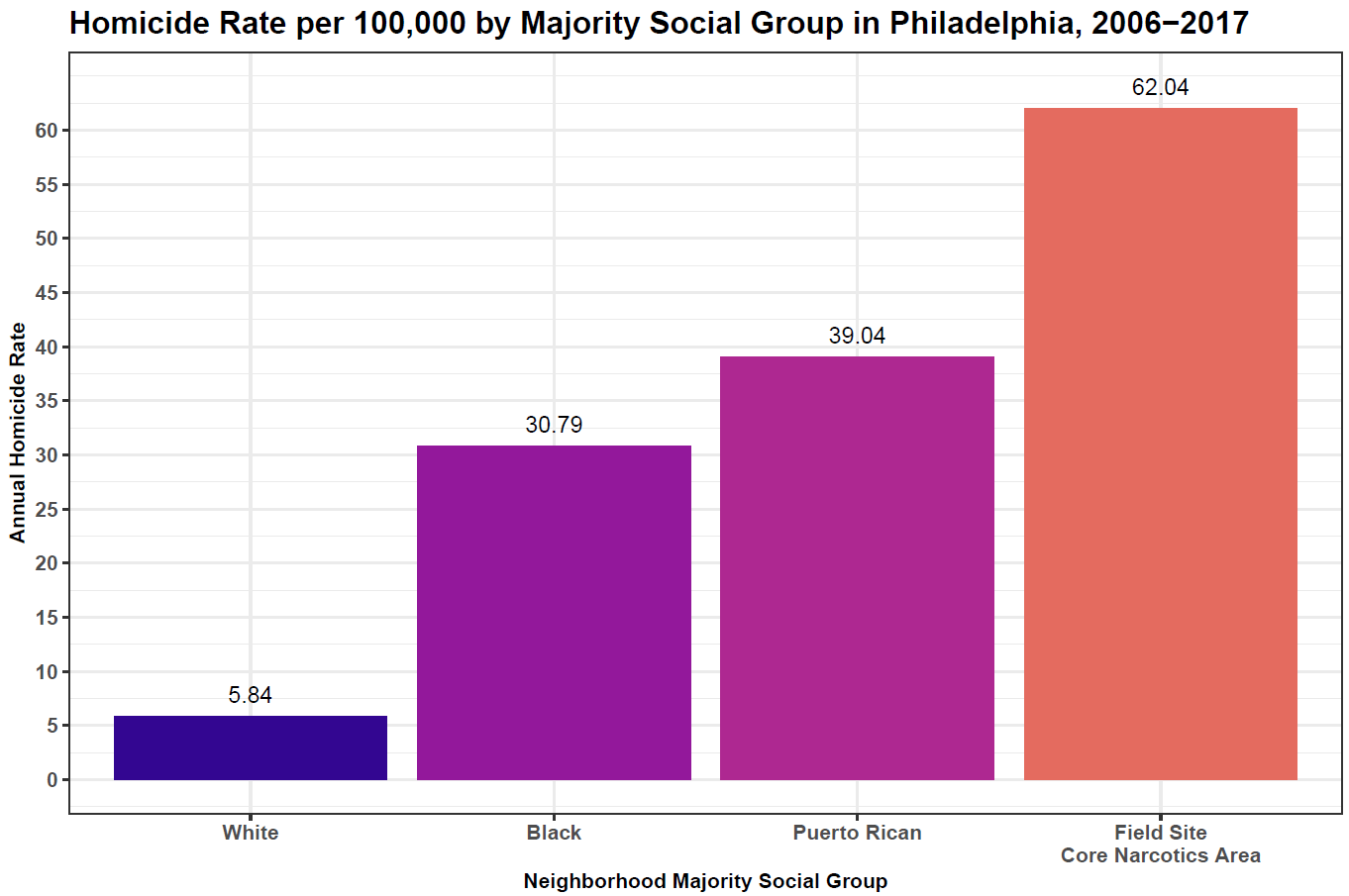

Of course, drug-dealing and the violence that results are common in other Philadelphia neighborhoods suffering from disinvestment, many of them predominantly Black. But it seemed to the researchers that the level of violence and drug activity where they were living was more extreme.

So they cross-referenced their observations and the interviews they had with neighbors and drug dealers with crime statistics for five census tracts bordered by Kensington Avenue to the east, Lehigh Avenue to the south, Fifth Street to the west, and Glenwood Avenue to the north.

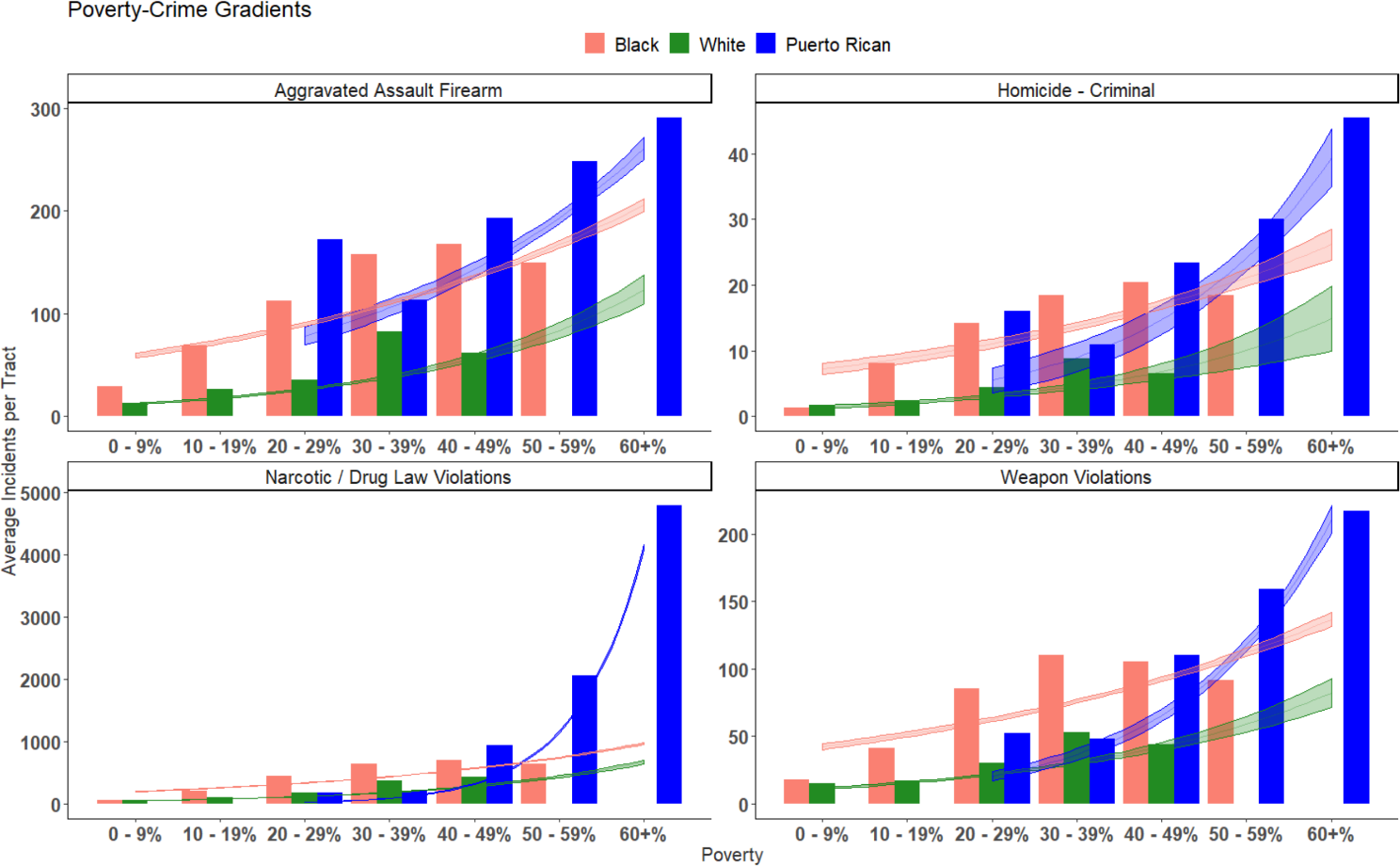

When adjusted for poverty, they found that the rates of narcotics crime, assaults and homicide were much higher in these majority-Puerto Rican census tracts than in majority-Black or majority-white ones.

Using statistical modeling, they predicted narcotics crime to be four times higher where they were living than in majority-Black neighborhoods with similar poverty levels.

Bars represent the average number of crime-related incidents per census tract, from 2006 to 2017, by percent of the population living in poverty, separate for majority-Puerto Rican, -black, and-white areas. The fitted lines represent model predictions from the Poisson regression, with 95% confidence intervals. (Plos One)

“We need to see the structural forces that drive what look like irrational killings,” said Bourgois. “In fact, tragically, killings often follow rational logics.”

In this case, the researchers found those to be the violent byproducts of the illegal narcotics economy: disputes over unpaid debts, monopoly control of territory and supply, and theft of drugs.

Bourgois had conducted similar research in the past. For his 1995 book, “In Search of Respect: Selling Crack in El Barrio,” he spent several years doing ethnographic research with socially marginalized, mostly Puerto Rican crack dealers and their families in East Harlem. He wrote another book that followed a group of people addicted to heroin in San Francisco’s drug scene for a decade.

Puerto Rican migration to Kensington

In the study, Bourgois and his team write that the poverty and violent crime Puerto Ricans in Kensington are especially vulnerable to results, in large part, from the geographic and economic conditions they encountered upon arriving in the mainland United States.

Historians chronicling the diaspora of Puerto Ricans in the 20th century have noted that after World War II, the agricultural economy in Puerto Rico began to dissolve, prompting thousands of rural farmers to move to industrial areas both on the island and on the U.S. mainland. Philadelphia boasted a diverse range of factory jobs then, many of them in North Philly’s Kensington neighborhood, so it was a logical choice. The new arrivals were U.S. citizens, which made migration easier.

During the 1950s, upward of 14,000 Puerto Ricans moved to Philadelphia. That number doubled over the next 20 years, making it the city with the third largest population of Puerto Ricans after New York and Chicago. (It has now surpassed Chicago). Many came because families or friends had already settled here.

But not long after Puerto Ricans began to arrive in Philadelphia in large numbers, business in the Kensington factories began to slow and white workers began to leave the neighborhood.

“As migrants struggled to recreate their household economies, Philadelphia shifted from a manufacturing to a service economy,” historian Carmen Whalen wrote in her 2001 book, From Puerto Rico to Philadelphia: Puerto Rican Workers and Postwar Economies. “Puerto Ricans who had made the city their home became displaced labor migrants.”

Bourgois and his fellow researchers write that in the decades after the factories closed, Kensington — known for drug activity even when its population was primarily white — and its Puerto Rican residents suffered neglect from both the public and private sectors.The segregated post-industrial neighborhood was ripe for the narcotics economy to take hold.

Operation Save the City founder Roz Pichardo, who is of Puerto Rican and Dominican descent and has lived in Kensington most of her life, said Puerto Ricans coming to Philadelphia today are still met with lack of opportunity. Since the island’s economic crisis began around 2006, and following Hurricane Maria in 2017, massive numbers of Puerto Ricans moved to the mainland United States. From 2010 to 2017, the Puerto Rican population in Philadelphia grew by two-thirds.

“People are brought from Puerto Rico with the promise of something,” said Pichardo. “Housing, better medical, and jobs. And when they get here, there’s nothing.”

Instead, Pichardo said, hundreds of newly arrived Puerto Ricans, who are U.S. citizens, are met with minimal state benefits. She pointed to low education levels and job skills, lack of ID, and a language barrier as impediments to employment for Puerto Ricans newly arrived in Philadelphia. And, for some, past criminal records make it even harder.

“Now, they’re stuck with doing what they think they know best, and that’s to sell,” she said.

And with selling drugs comes violence.

“Any time you make drugs illegal, it inherently generates violence,” said Friedman, the researcher who did the statistical analysis for the Kensington study. Because the narcotics economy operates outside a legal framework, guns become the only viable mechanism for enforcing contracts and ensuring debts are paid.

How does race factor in?

Kensington’s proximity to the I-95 corridor along the East Coast is often given as one explanation for the easy transportation of drugs and customers coming from elsewhere.

But during their time getting to know their neighbors, the researchers say, they heard another explanation from drug users and dealers alike: that because Puerto Ricans are a racially diverse group, the Kensington enclaves are less racially polarized, leading the dealers there to be generally more accepting of white heroin buyers than dealers in mostly Black neighborhoods.

Bourgois said the first person to explain that to him was a Black dealer who commuted to Kensington to sell heroin.

“If these people walked onto my block with cash in their hands, someone would take their money. Matter of fact, [laughing] I might,” Bourgois quotes the dealer as telling him in the study.

Pichardo, who started the anti-violence nonprofit Operation Save Our City, disagreed with that analysis. She said that Kensington has gained a reputation as the heroin capital of the world, and that people in active addiction will buy good product no matter the race of the seller.

“People will go anywhere where there’s good stuff, and the stigma around Kensington has always been, ‘We got the good stuff,’ ” she said, noting that Kensington was known as a place to buy drugs long before it became predominantly Puerto Rican.

“It’s always been that way,” she said. “So it’s not going to change because a white person now owns the block or a Puerto Rican person now owns the block.”

The researchers noted that white heroin buyers also said they felt less likely to be profiled by police as drug users in a neighborhood where they stood out less.

But members of the research team themselves were racially profiled by police in Kensington — white ones as potential drug buyers and the Latino researcher as a potential drug seller. Montero Castrillo, who lived in the apartment full time, was continually harassed by police in the neighborhood — especially when he was seen talking to white people.

“If we were just walking down the street chit-chatting with Fernando, because he looks Latino and we look white, we would start getting harassed by the police,” said Bourgois.

The pattern was so clear that Montero Castrillo became part of a class-action lawsuit filed against the Philadelphia Police Department in 2010, accusing officers of racially biased stop-and-frisk practices. The lawsuit resulted in a 2011 consent decree that requires that police stop suspects only when there is a reasonable suspicion of criminal conduct and only frisk them when an officer suspects someone is armed and dangerous.

A 2017 American Civil Liberties Union report, the result of a monitoring process stipulated by the consent decree, found that police have not stopped the practice. In May of this year, then-Police Commissioner Richard Ross defended the practice before City Council while also noting that it was a tool that should not be abused.

Montero Castrillo’s experience, along with Bourgois’ arrest — which Bourgois said was accompanied by a couple of broken ribs and a lot of mockery from the officers — made the team more wary of police than of drug dealers or neighbors.

“I was scared of these guys, they’re scary guys!” Bourgois said of the police. “They have guns and batons, and they can plant fake charges on you.”

The limits of policing

Their years spent living in and visiting Kensington made the research team skeptical of any degree of police intervention as an effective way to combat the drug economy. They believe that massive sweeps like the one that ended with Bourgois’ arrest don’t actually deter crime and instead merely cycle people through the criminal justice system. More targeted raids at higher-level drug dealers leave power vacuums, and the competition over filling them can lead to still more violence.

As a result, the researchers recommend a “Marshall Plan-level investment” of social services and job creation in the neighborhood, a nod to the $12 billion aid package that the U.S. government gave to Western European countries to help rebuild after World War II. The logic? It was economic disinvestment that got us into this mess, it should be economic solutions that get us out.

“People tend to focus on people who use drugs, and say, well, the drug dealers are still morally bankrupt,” said Friedman. But doing that ignores the policies and structures that may force poor Puerto Rican residents of Kensington into narcotics economies, he said.

Friedman also pointed to drug decriminalization as a way to relieve some of the trauma and damage to communities incurred by cycles of arrest and incarceration.

District Attorney Larry Krasner is in the process of decriminalizing low-level drug-possession offenses.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.