Cuban immigrants detained by ICE in York for more than a year, despite federal court ruling

Abel Perez, 27, and Pablo Alvarez, 26, both arrived from Cuba at the U.S. southern border in December 2017. Both applied for asylum, and have been held ever since.

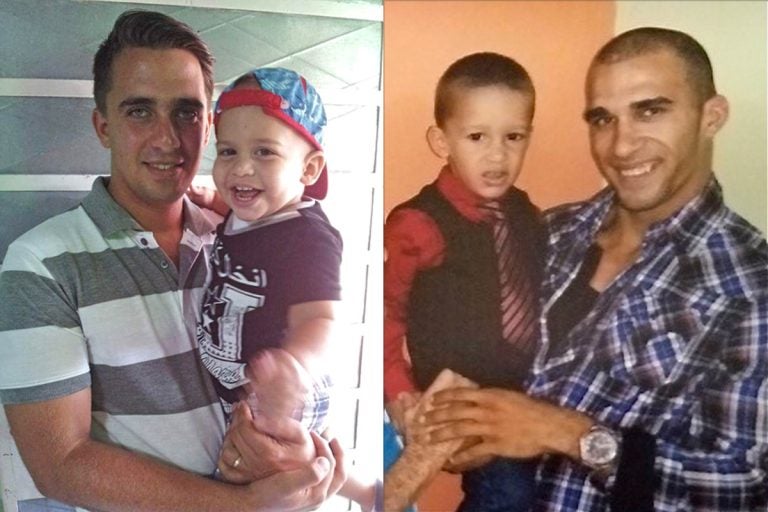

Abel Perez (left) and Pablo Alvarez (right), are pictured holding their sons. (Courtesy of Church World Service)

Two men from Cuba have been held in immigration detention in York County Prison for more than a year, despite a federal court ruling that says ICE officials in Pennsylvania were wrongly denying requests for release.

Abel Perez, 27, and Pablo Alvarez, 26, say they they fled political persecution in the island nation about 90 miles from Florida. Shortly after presenting themselves at the U.S.-Mexico border in late 2017, they were transferred to York.

Their cases illustrate how Cubans’ favorable treatment in the U.S. immigration system, a vestige of the Cold War, collides with tightening regulations around migration to this country.

“We … came to this great country fleeing the oppression and persecutions Cubans suffer at the hands of the established dictatorship,” wrote Perez and Alvarez in a statement shared by their attorneys. “We don’t believe it’s been fair to have been detained for 16 months, when the only crime we have committed, if you can call it that, is to have arrived at the southern border asking for asylum.”

‘Just the luck of the draw’

Cubans in the United States continue to enjoy a relatively easy path to citizenship through the Cuban Adjustment Act of 1966. Under that law, Cuban nationals lawfully present for one year can apply for a green card.

However, since early 2017, the neck of the funnel into the U.S. has tightened for many immigrants. In January of that year, President Barack Obama ended the “wet-foot, dry-foot” policy, which had granted any Cubans who reached American soil permission to stay. The Trump administration also reversed some of Obama’s efforts to improve relations with the country’s communist government, and just this month slapped new sanctions on Cuba.

“The economic picture in Cuba is dismal, the relationship with the U.S. is getting worse by the minute,” said attorney and University of Miami lecturer Pedro Freyre, an expert on Cuban-American relations.

Against this backdrop, more Cubans are following migrant routes through Central America and Mexico to petition for entry at the U.S. border.

That’s what Perez and Alvarez did. In December 2017, they requested asylum at the Port of Entry in Laredo, Texas.

Shortly thereafter, “by no fault of their own, just the luck of the draw, [they were] sent to York County Prison,” said Carrie Carranza, an immigration legal defense advocate with the group Church World Service in Lancaster.

They happened to be transferred at the exact time that a judge would later rule ICE leadership in Pennsylvania had been unlawfully detaining asylum seekers.

Both Perez and Alvarez passed what’s called a “credible fear interview,” the first test in claiming legal status in the U.S. because an immigrant fears returning to their home county. Normally, that would prompt ICE to evaluate whether or not Perez and Alvarez needed to stay in detention.

In July 2018, U.S. District Court judge James E. Boasberg ruled that Philadelphia’s ICE Field of Office, along with four others, had been failing to do those individual evaluations, and was instead detaining asylum seekers at near-automatic rates, in violation of its own policies. He ordered them to stop.

After that federal court decision, a half-dozen Cuban migrants who had been held at York were released, according to immigration attorney Brennan Gian-Grasso — but not Alvarez and Perez. ICE officials later explained the agency had classified them as “flight risks.” Gian-Grasso said the only difference between those released and those detained was the type of relative sponsoring them — a sibling, versus an aunt or cousin.

Both have been ordered removed, and their immigration proceedings are ongoing, according to ICE officials.

Families in limbo

Perez and Alvarez’s family members say they are now left in the lurch, wondering what will happen.

“The plan was that he was going to come live with me,” said Norlys Grillo Alvarez, Pablo Alvarez’s aunt. She lives in Bradenton, Florida and is a U.S. citizen.

Alvarez was targeted for doing construction work for a member of the protest group Las Damas de Blanco in Cuba, and has been jailed by the Cuban government, according to Grillo Alvarez.

“It’s impossible living in Cuba … You can’t express anything. If you say anything, they punish you,” she said.

Perez was a pilot in Cuba, but refused to fly for the military, earning him the ire of the communist government, according to Gian-Grasso. His cousin, Lissette Barquin Borges, came to the United States in the 1970s and planned to sponsor him financially, so that one day he could get a pilot’s license in this country.

“I feel like he could be a companion for me, like the son that I never had,” said Barquin Borges, who has two daughters.

During their time in detention, Alvarez and Perez also suffered setbacks in their asylum cases. Both received denials and have appealed. Had they been released when they were first eligible, that case would now be irrelevant, said Carranza.

“If they were granted parole, they would likely have green cards by now,” she said.

Instead, they face deportation. Church World Service has taken up their cause, asking ICE to take a second look at their requests for parole.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.