How will life change once the COVID-19 emergency ends?

Here’s a look at what will stay and what will go once the emergency order is lifted.

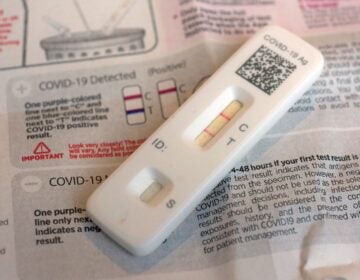

A nurse prepares for a COVID-19 test outside the Salt Lake County Health Department, Dec. 20, 2022, in Salt Lake City. The declaration of a COVID-19 public health emergency three years ago changed the lives of millions of Americans by offering increased health care coverage, beefed up food assistance and universal access to coronavirus vaccines and tests. Much of that is now coming to an end, with President Joe Biden's administration saying it plans to end the emergencies declared around the pandemic on May 11, 2023. (AP Photo/Rick Bowmer, File)

The declaration of a COVID-19 public health emergency three years ago changed the lives of millions of Americans by offering increased health care coverage, beefed-up food assistance and universal access to coronavirus vaccines and tests.

Much of that is now coming to an end, with President Joe Biden’s administration saying it plans to end the emergency declarations on May 11.

Here’s a look at what will stay and what will go once the emergency order is lifted:

COVID-19 tests, treatments, and vaccines

The at-home nasal swabs, COVID-19 vaccines as well as their accompanying boosters, treatments and other products that scientists have developed over the last three years will still be authorized for emergency use by the Food and Drug Administration once the public health emergency is over.

But how much people pay for certain COVID-related products may change.

Insurers will no longer be required to cover the cost of free at-home COVID-19 tests.

Free vaccines, however, won’t come to an end with the public health emergency.

“There’s no one right now who cannot get a free vaccine or booster,” said Cynthia Cox, vice president at Kaiser Family Foundation. “Right now all the vaccines that are being administered are still the ones purchased by the federal government.”

But the Biden administration has said it is running out of money to buy up vaccines and Congress has not budged on the president’s requests for more funding.

Many states expect they can make it through the spring and summer, but there are questions around what their vaccine supply will look like going into the fall — when respiratory illness typically start to spike, said Anne Zink, the president of the The Association of State and Territorial Health Officials.

“We’re all anxious to find out more about that,” Zink said.

Medicaid

Medicaid enrollment ballooned during the pandemic, in part because the federal government prohibited states from removing people from the program during the public health emergency once they had enrolled.

The program offers health care coverage to roughly 90 million children and adults — or 1 out of every 4 Americans.

Late last year, Congress told states they could start removing ineligible people in April. Millions of people are expected to lose their coverage, either because they now make too much money to qualify for Medicare or they’ve moved. Many are expected to be eligible for low-cost insurance plans through the Affordable Care Act’s private marketplace or their employer.

Student loans

Payments on federal student loans were halted in March 2020 under the Trump administration and have been on hold since. The Biden administration announced a plan to forgive up to $10,000 in federal student loan debts for individuals with incomes of less than $125,000 or households with incomes under $250,000.

But that forgiveness plan — which more than 26 million people have applied for — is on pause, thrown into legal limbo while awaiting a ruling from the Supreme Court.

The Justice Department initially argued that the Secretary of Education has “sweeping authority” to waive rules relating to student financial aid during a national emergency, per the 2003 HEROES Act that was adopted during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

A Biden administration official told The Associated Press Tuesday that ending the health emergencies will not change the legal argument for student loan debt cancellation, saying the COVID-19 pandemic affected millions of student borrowers who might have fallen behind on their loans during the emergency.

The pause on student loan payments is expected to end 60 days after the Supreme Court ruling.

Immigration at the border

Border officials will still be able to deny people the right to seek asylum, a rule that was introduced in March 2020 as COVID-19 began its spread.

Those restrictions remain in place at the U.S.-Mexico border, pending a Supreme Court review, regardless of the COVID-19 emergency’s expiration. Republican lawmakers sued after the Biden administration moved to end the restrictions, known as Title 42, last year. The Supreme Court kept the restrictions in place in December until it can weigh the arguments.

The end of the emergency may bolster the legal argument that the Title 42 restrictions should no longer be in place. The emergency restrictions fell under health regulations and have been criticized as a way to keep migrants from coming to the border, rather than to stop the spread of the virus.

Telehealth

COVID-19′s arrival rapidly accelerated the use of telehealth, with many providers and hospital systems shifting their delivery of care to a smartphone or computer format.

The public health emergency declaration helped hasten that approach because it suspended some of the strict rules that had previously governed telehealth and allowed doctors to bill Medicare for care delivered virtually, encouraging hospital systems to invest more heavily in telehealth systems.

Congress has already agreed to extend many of those telehealth flexibilities for Medicare through the end of next year.

Food assistance

Relaxed rules during the COVID-19 public health emergency made it easier for individuals and families to receive a boost in benefits under the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP. Some state and congressional action has started to wind down some of that. Emergency allotments — typically about $82 a month, according to the Food Research and Action Center — will come to an end as soon as March in more than two dozen states.

Food help for unemployed adults, under the age of 50 and without children, will also change after the public health emergency is lifted in May. During the emergency declaration, a rule that required those individuals to work or participate in job training for 20 hours per week to remain eligible for SNAP benefits was suspended. That rule will be in place again starting in June. SNAP aid for more low-income college students will also draw down in June.

State COVID emergencies

At least a half-dozen states — including California, Delaware, Illinois, New Mexico, Rhode Island and Texas — have some form of COVID emergency declaration or disaster order still in place. But those orders have limited practical effect.

New Mexico’s public health emergency, which has been extended through Friday, advised health care facilities to abide by federal coronavirus requirements. Delaware has continued to operate under a “public health emergency,” which has suspended staffing ratios in long-term care facilities.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom, a Democrat, has said his emergency order will end Feb. 28. Newsom has issued 596 specific orders, from stay-at-home mandates to tax-filing extensions, during the pandemic. Most have expired, but he plans to ask lawmakers make two into permanent laws — one letting nurses order and dispense COVID-19 medication and another allowing lab workers to solely process coronavirus tests.

Money for hospitals

Hospitals will take a big financial hit in May, when the emergency comes to an end. They’ll no longer get an extra 20% for treating COVID-19 patients who are on Medicare.

The end to those payments comes at a time when many hospitals are under financial pressure, struggling with workforce shortages and dealing with the pain of inflation, said Stacey Hughes, the executive vice president at the American Hospitals Association.

—

Associated Press writers JoNel Aleccia in Los Angeles, Colleen Long and Seung Min Kim in Washington and David Lieb, in Jefferson City, Missouri, contributed to this report.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)