Constitution Center focuses on religious freedom’s evolution from a concept to a right

ListenDid the Founding Fathers base the new nation on a foundation of religious ideals?

According to the historical documents assembled at the National Constitution Center, the answer is yes. And no.

It’s complicated.

In anticipation of the visit by Pope Francis next month, the Constitution Center transformed what had been a small hallway off its main lobby into an exhibition space.

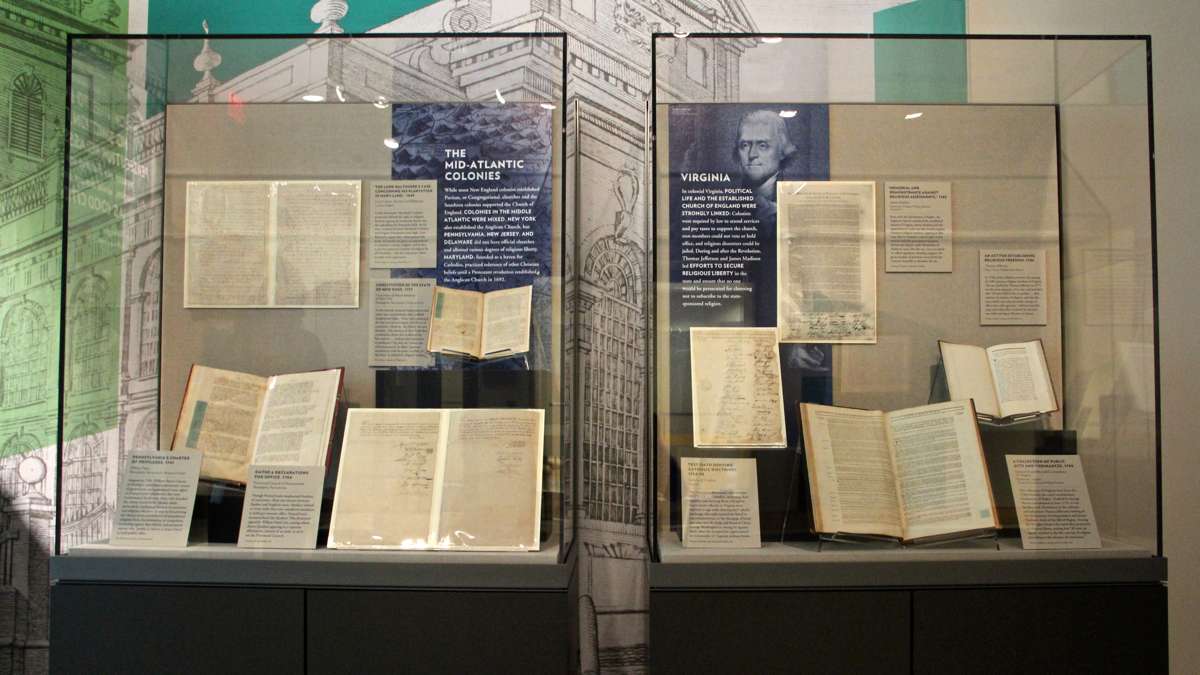

“Religious Liberty and the Founding of America” is a collection of historic documents tracing the evolution of language on religion that would become the First Amendment.

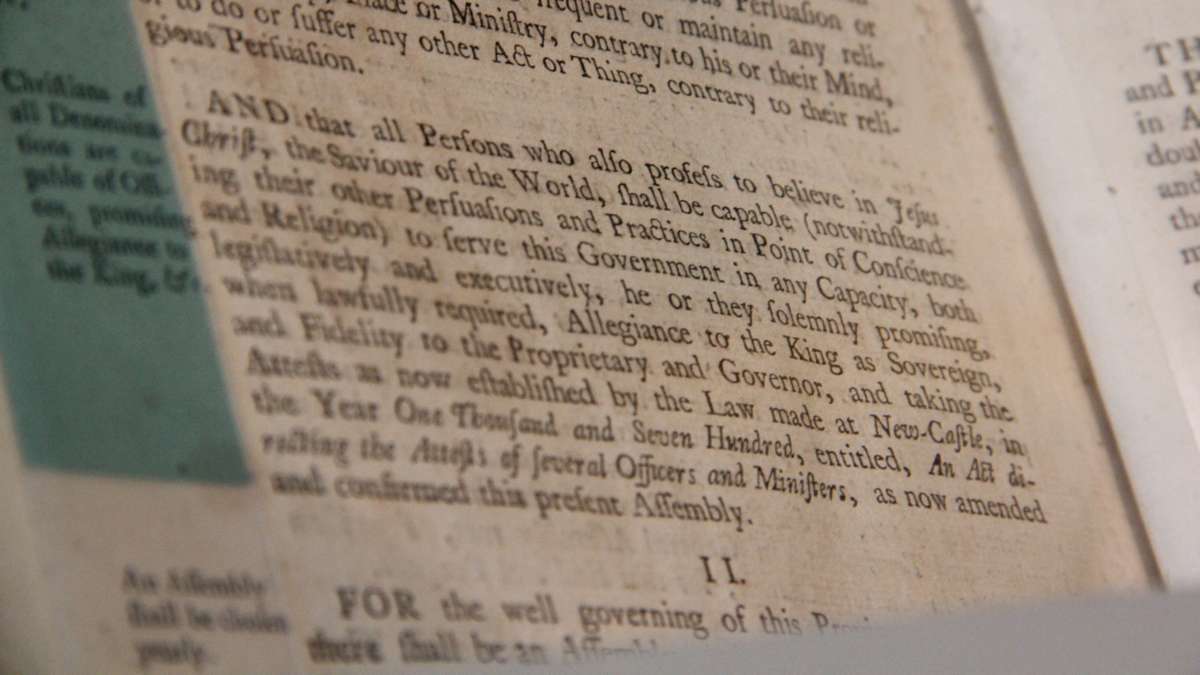

Nine of the original 13 Colonies had provisions in their individual charters restricting voting, military service, and sometimes even property ownership to those of a particular religion. Pennsylvania’s charter was somewhat liberal, allowing members of any religious sect to participate in political life, as long as they believed in Jesus Christ.

When James Madison came up with the idea that people have the right to worship according to “the dictates of conscience,” that rubbed states the wrong way.

“There was a profound tension between this tradition of Colonial established churches and this new, radical belief coming from the Enlightenment and John Locke,” said Jeffery Rosen, president and CEO of the Constitution Center. “The right to worship God according to ‘the dictates of conscience’ is an unalienable individual right, and that’s completely inconsistent with the idea of established churches.”

The phrase “according to the dictates of conscience” appears in Virginia’s Bill of Rights written by George Mason. Later, Madison would use it when drafting Amendments for the Bill of Rights, pushing to eradicate an official religion for the new nation.

The idea of established religion took a long time to shake off.

The Constitution Center has some of the early drafts of the Bill of Rights as those amendments made their way through the houses of government. They show the Senate trying to weaken the language concerning religious liberty.

“The Senate is trying to hedge its bets: ‘Congress has no right to establish articles of faith, or a mode of worship,'” said Rosen. “But the House says unequivocally that you cannot have a federal established church.”

There is still some wiggle room in the First Amendment regarding established religion. Advocates of states’ rights can point out that absolute freedom of religion applies to the federal government only, leaving states free to establish their own official religions.

“In fact, there are some Supreme Court justices who believe today that [the phrase] ‘Congress shall make no law respecting the establishing of religion’ was meant to prevent Congress from disestablishing state churches,” said Rosen. “It was an antidisestablishment provision. That’s the only time I’ve been able to use that SAT word.”

Rosen added that, while the argument for the establishment of state religion occasionally arises (in particular by Justice Clarence Thomas), it is not generally accepted by the Supreme Court.

The exhibition also includes letters sent between George Washington and various religious leaders on the event of his election, in which the new president assures them they will all have a place at the national table.

Washington also exchanged letters with Jewish leaders. Some of those letters are across the Mall from the Constitution Center, at the National Museum of American Jewish History.

Despite heavy security measures, both the Constitution Center and the Museum of American Jewish History will be open during Pope Francis’ visit to Independence Mall. Both buildings are inside the fenced zone, accessible only by pedestrians who have gone through metal detectors.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.