Community meeting on the future of PES refinery was packed, loud and divided

People who live near the South Philly refinery said they want it shut and gone forever, while laid-off refinery workers are hoping someone will buy it.

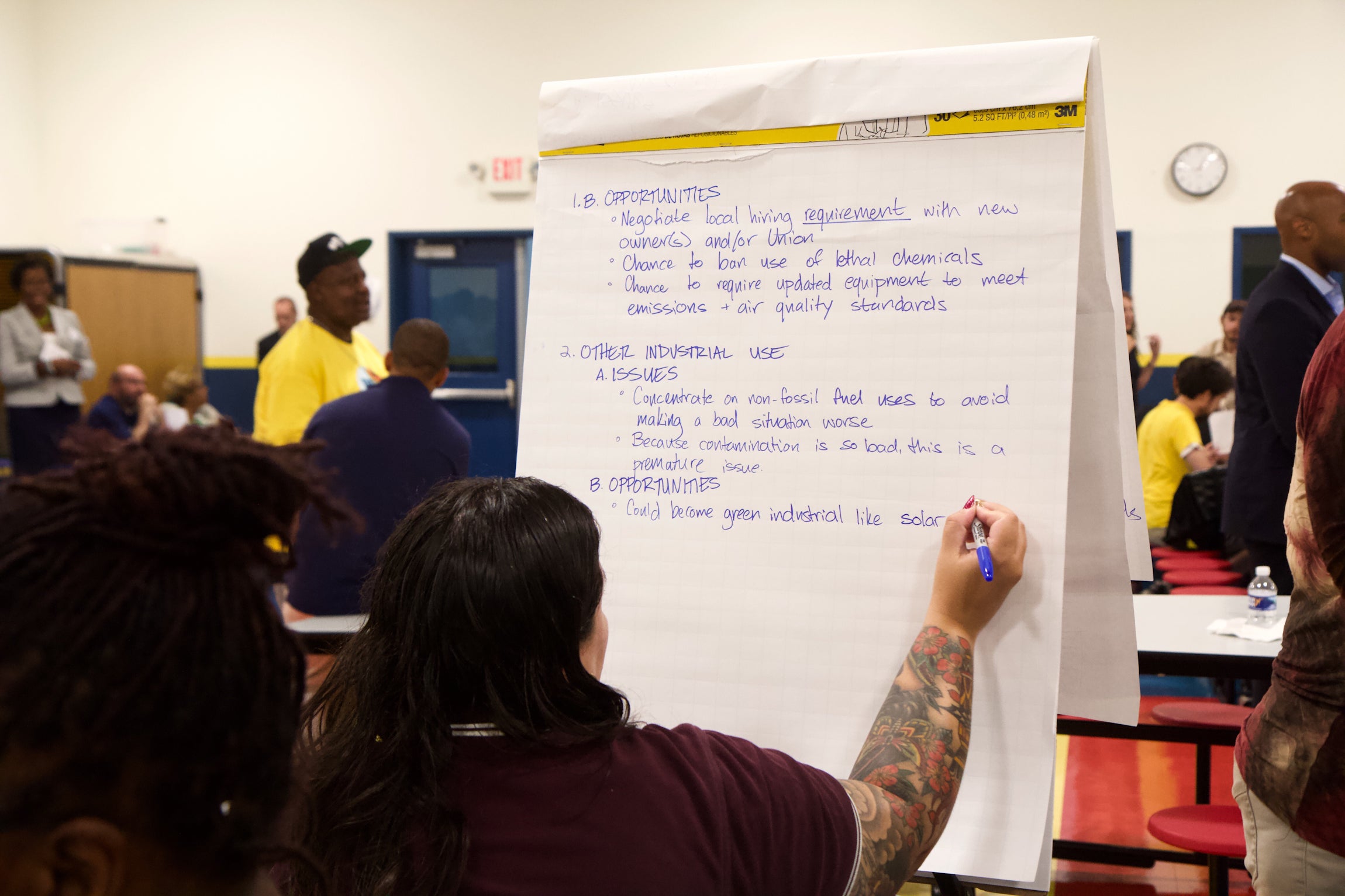

Members of the Southwest Philadelphia community discuss ideas for what to do at the PES refinery. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

It was the community’s turn to say what should be done with the Philadelphia Energy Solutions refinery. An explosion and massive fire destroyed part of the South Philly complex two months ago, and more than 100 people filled Preparatory Charter School’s hall Tuesday night for the second public meeting of the city’s advisory group.

People who live near the PES refinery said they want the facility shut and gone forever. Laid-off refinery workers are hoping someone will buy it.

The refinery is the largest in the northeastern United States and the city’s biggest single polluter.

“You can’t turn this land into anything else, it’s been refinery for 120 years,” said Patrick Felix, a Fishtown resident who has worked at the refinery for the last 17 years. “Two billion dollars is the number that they’re putting on remediating this site.”

Refineries have operated at the location since 1866. Soil and groundwater there are contaminated with petroleum hydrocarbons. Sunoco, the facility’s former owner, has been cleaning up the site for the last 10 years.

“I want it closed, permanently,” said Carol Hemingway, a member of the activist group Philly Thrive who has lived about six blocks from the refinery for 25 years. “Philadelphia should be trying to be a premier city in showing the rest of the country how we can use a different kind of fuel to fuel our city.”

While working as a social worker in the community in the past, Hemingway said, she often asked herself why so many people living in the area had respiratory diseases. She herself had cancer. Now, she attributes the health issues suffered by the refinery’s neighbors to air pollution released by the facility.

Public health experts say it is difficult to link any particular illness directly to the refinery. That’s because the refinery is not the only source of air pollution in Philadelphia, and because diseases like asthma have a number of causes.

Tuesday night’s meeting was more participatory than the city advisory group’s first public meeting, but it also was a bit more chaotic. Those in attendance, who either lived or worked in the community, split into small groups around dozens of tables set up at the Point Breeze school. Some of the advisory board’s 30 members walked among the attendees, but were never identified.

The meeting was packed, it was loud, and it was divided. At times, union workers and local residents clashed and shouted at one another from table to table. Tension was palpable. With Philly Thrive members in their yellow shirts and union members wearing blue and red, members of the city Planning Commission and other officials worked as moderators, guiding the conversation around issues regarding the future use of the refinery site.

Yet as city Managing Director Brian Abernathy noted in his welcome statement, Philadelphia has very limited power over what ultimately happens at the 1,300-acre refinery site because it is private property. He added that the city has doubled the number of members of the advisory group’s community committee by adding four community leaders — all black — after hearing at the last meeting complaints of insufficient neighborhood voices and about the racial makeup of the group.

“We took that feedback to heart,” said Abernathy.

In a separate auditorium, participants were encouraged to talk about their experiences living or working in the community in front of a video camera, in written testimony, or with drawings. Tension often rose between union members and activists during the recording.

Anton Moore directs the South Philadelphia nonprofit Unity in the Community. He also is part of the community committee of the city’s refinery advisory group.

“We have a lot of people who have felt like their health concerns are from the refinery. But then you have a lot of people who are losing jobs, and when it is tough to feed your family, that sinks you into a deep depression and messes with your health. So you got two issues on the table right now.”

Moore said there has to be a way to meet in the middle.

It’s about losing a community, workers say

Members of United Steelworkers Local 10-1 attended Tuesday’s community meeting en masse. Earlier in the day, PES laid off almost half of its union workers. The rest will be let go sometime before Sunday.

Felix, the refinery worker from Fishtown, said that Friday will be his last day at work, but that he hopes another oil company reopens the site — USW Local 10-1 president Ryan O’Callaghan said he has met with a potential bidder for the refinery but can’t disclose details.

“[We’re feeling] anger, resentment. This company treated us like trash,” Felix said. “They gave us no information, they told us nothing. Everything was, ‘We don’t know,’ ‘We’re talking about it.’ So, they could have done the right thing and let people know what was going on, and you had to find out like it was a secret. It’s terrible. Horrible, horrible company.”

O’Callaghan said the early layoffs are affecting the employees, who are losing not only their jobs, but also their community.

“My members are concerned that their voices aren’t being heard. So they want to make sure that they show a presence, that these jobs mean something also that the refinery can start right now and run safely,” O’Callaghan said.

Alex Clowes, an operator at the refinery, said the plant could be running safely. Only one unit out of 30-plus units was damaged, he said. Instead, Friday will be his last day at the place he’s been spending most of his time for 29 years.

“It’s my family here. I spend more waking hours with the people in this refinery and in this community than my own blood,” he said. “And I put a lot in here — it’s going to be tough going on.”

Clowes said he’s been looking for any job in the tri-state area to try not to move his family, but nothing is coming up.

“The next step is to file for unemployment, which is another burden on the city and in the community, and I’ve never done that in my life and I don’t want to have to do that,” Clowes said.

Deborah Rizzo’s husband worked at the refinery for over 20 years. She said the city should find a solution to rebuild the refinery and keep the jobs going.

“The impact on the pollution? Here’s me — I’m healthy as a horse, and I’ve been near the refinery all my life, all my life. I have no problem with the refinery. My kids are healthy, my parents are healthy — they live in Southwest Philly — [there are] plenty, plenty of people that are fine,” she said.

Rizzo added there’s nothing else that could be built on that site safely.

“If they build something over there, say a park or something, they’re going to have a hell of a lot of environmental problems then because they’re going to be sitting on it, they’re going to be playing ball on it, they’re going to be mowing it. … So are they not afraid of something going there and down the line really, really, really hurting people? When right now we have it contained, you have it viable, you have people with jobs,” she said.

A new public meeting focusing on employment will take place Wednesday night. The advisory panel’s environment committee will meet Aug. 27, and its business committee will meet Sept. 9. All meetings are held at Preparatory Charter School in Point Breeze. The public can also submit written comments.

The city has created a special website with details of the process coming forward, and will issue a report with recommendations by fall.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.