Community Farm in South Kensington claiming its ground in court

On Friday afternoon, Clifford Brown planted beet seeds in tidy rows at La Finquita, a volunteer-run market farm in rapidly redeveloping South Kensington. It’s spring business-as-usual for this 28-year-old urban farm, which grows produce for neighborhood soup kitchens and hosts an affordable fresh food farmstand on Sundays during the growing season.

Sparks flew as Brown, the farm manager, sawed off a lock someone had put on the garden’s Master Street gate.

Both the seeds and the sparks were expressions of ownership, which the garden community was also asserting in court that day.

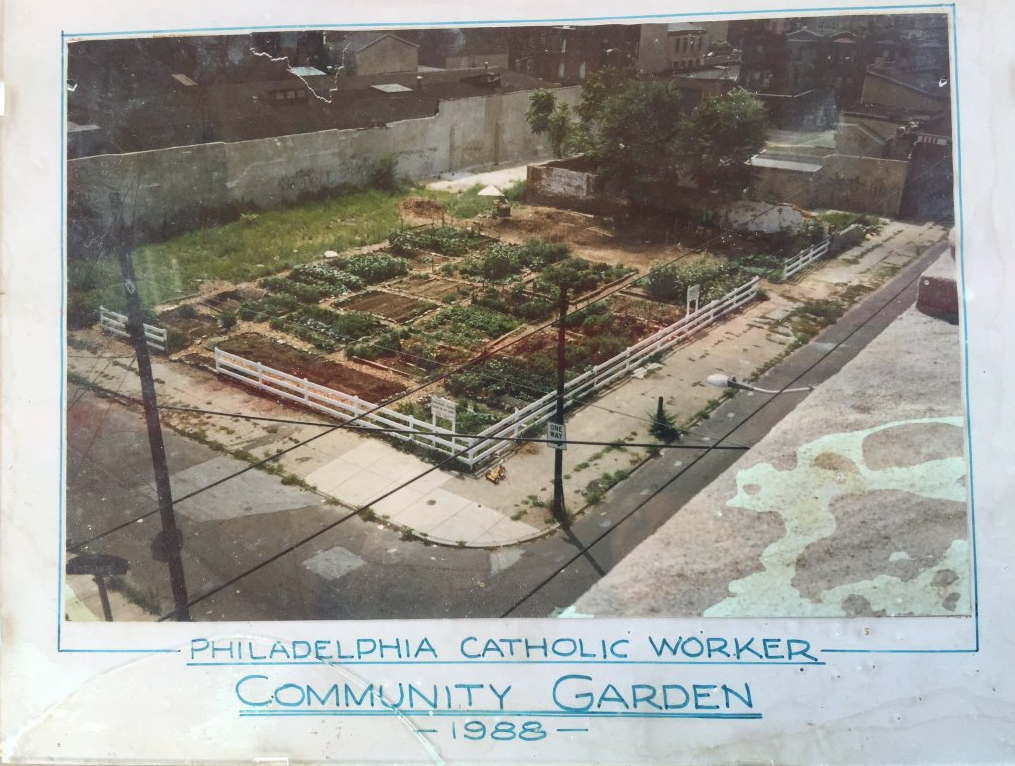

Philadelphia Catholic Worker, a religious nonprofit located a block from the farm, has maintained and cultivated this ex-industrial property continuously since 1988. On Friday it filed litigation in the Philadelphia Court of Common Pleas to establish its clear ownership of the property by adverse possession.

The grounds? Its uninterrupted, 28-year garden tenure. At stake? A community-driven green space—itself increasingly rare turf in this changing neighborhood— where recent and longtime residents find common ground and help produce fresh affordable food for the neighborhood.

“We have about 50 active volunteers, young and old, new to the neighborhood and have been in the neighborhood for a long time,” said gardener Shazana Goff. The youngest is 13. The oldest has been in the neighborhood since 1951. Eight original garden plots exist, but volunteers cultivate the rest of the property. Every volunteer donates time and effort in exchange for 50 percent off the farm’s produce sold at the weekly farmstand.

Before this lot at the corner of Lawrence and Master streets was growing produce, the property was an abandoned, vacant parcel. Its last owner, Pyramid Tire & Rubber Company, has been inactive as a corporation since 1956. The property has been tax delinquent for six decades.

Philadelphia Catholic Worker reclaimed the property from illegal dumping and abandonment in the late 1980s by clearing the lot and starting a community garden. In 1988, a fence went up, and permits were secured to use the fire hydrant across the street as a water source. Over time they’ve received support from Philadelphia Green, the Parks Department, Philadelphia Horticultural Society, and plenty of neighbors.

“It’s been operating continuously, openly, notoriously, and adverse to Pyramid since 1988,” said Amy Laura Cahn, staff attorney at the Public Interest Law Center, co-counsel on the case. State law requires that Philadelphia Catholic Worker demonstrate unbroken use and possession for 21 years, without permission of the property’s owner of record, in order to claim the property by adverse possession. “We are now 28 years in and Philadelphia Catholic Worker is still a block away, they are still hosting the garden.”

Adverse possession isn’t often used here, but there is local precedent for another long-tenured garden, the Central Club for Boys and Girls in Point Breeze, secured ownership of their property in 2010 using an adverse possession claim.

Like gardeners at plenty of other long-tenured city gardens on once-vacant lots, La Finquita had hoped the Philadelphia Land Bank would provide a pathway for Philadelphia Catholic Worker to secure permanent ownership of the property. Even though protecting gardens like La Finquita is among the Land Bank’s explicit goals, it is not yet able to acquire privately owned tax-delinquent parcels for disposition to new owners. La Finquita could no longer afford to wait.

Earlier this year the garden’s gates were locked and No Trespassing signs were posted. An entity called Mayrone LLC filed a deed for the property in late February, showing a purchase from the co-executors of the last beneficiary of the estate of the defunct company. Along with the purchase, Mayrone paid the back taxes.

But the legal complaint filed Friday asserts that the property wasn’t theirs to sell, and asks the court to affirm that the Philadelphia Catholic Worker is the owner.

“We are all staying very positive. We have so much support from people in the neighborhood, businesses, gardeners, people in our community,” said Goff. The garden’s perennials are waking up and spring planting will continue undeterred. “We’re going to have our first official workday next week.”

La Finquita is hardly alone as a long-tenured urban garden that lacks clear ownership. Amy Laura Cahn rattles off a handful of sites on similarly precarious ground. Absent a fully functioning land bank to facilitate land transfers that ensure the stability and longevity of these gardens, urban agriculture continues faces an uphill battle in neighborhoods across the city.

“It’s taking a long time to overcome the notion of gardens as interim use,” Cahn says. That’s despite the city’s sustainability agenda, the enormous investments by the Philadelphia Water Department in green stormwater infrastructure, the importance of food access, and awareness that cities need green spaces to combat urban heat. “All of these things that we know now and you still have to go up against the notion that gardens are an interim use and are awaiting a higher and better use. If we think that there’s always a higher and better use than a garden, then we will never have a garden. It is absolutely an environmental justice issue. It is an equity issue.”

Gardeners hope the court will enable Philadelphia Catholic Worker to establish clear ownership of the land, enabling a long-term plan for the space.

To Goff and her fellow gardeners, La Finquita is a precious asset.

“We walked around the entire neighborhood and there’s nothing like this left,” she said. “In every square inch of South Kensington, this is it.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.