Communities with casinos in Pennsylvania concerned about possible funding changes

Listen

Players try their luck on the slot machines at the Hollywood Casino at Penn National Race Course in Dauphin County, Pennsylvania. State lawmakers have until the end of May to fix a section of the state’s gaming law that the Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled unconstitutional. The part of the law that came into question involves the local share tax. (Lindsay Lazarski/WHYY)

When playing the slots in Pennsylvania, casinos and gamblers aren’t the only ones making money.

The state collects 54 cents for every dollar a player loses in a slot machine.

The state uses most of that money, about 34 cents, for reducing property taxes. The state’s horse racing industry gets 11 cents and 5 cents goes to a state economic development trust fund. The remaining 4 cents is split among the communities that host the casino.

That last amount — known as the local share tax — could soon change because of a decision handed down from the Pennsylvania Supreme Court last September.

The court ruled that part of the state’s gaming law was unconstitutional.

Under the original law, most casinos — except the one in Philadelphia and smaller boutique casinos — must pay whichever is greater: either $10 million or 2 percent of their slots gross terminal revenue.

Since 2006, when the first casino in Pennsylvania opened its doors, no casino has ever reached the $10 million threshold from 2 percent of their slot machines.

Last year, for example, casinos paid an additional $2.4 – $7.8 million each to reach the local share tax amount required by law.

Casinos that make less money in slots, as a result, end up paying more money to the local share tax.

Mount Airy Casino Resort challenged the law in the state’s Supreme Court, claiming it was being taxed unfairly.

Michael Sklar, an attorney representing Mount Airy, said the casino should be taxed at a percentage — not a flat rate — and that percentage should be applied across the board to all casinos.

“We’re not saying for a second that there shouldn’t be a local share tax,” said Sklar. “It just has to be done in a constitutional and responsible way.”

Despite the lawsuit, Sklar said Mount Airy considers itself a good neighbor. The casino made an initial $350 million initial investment in the business, employs nearly 1,100 workers, and is the largest property taxpayer in Monroe County.

Since the court ruled in Mount Airy’s favor, it’s now up to the state legislature to fix the law.

Impact on Local Communities

Paradise Township is a sleepy and bucolic town in the Pocono Mountains — where hiking trails, fishing streams, and the Mount Airy Casino Resort are valuable amenities.

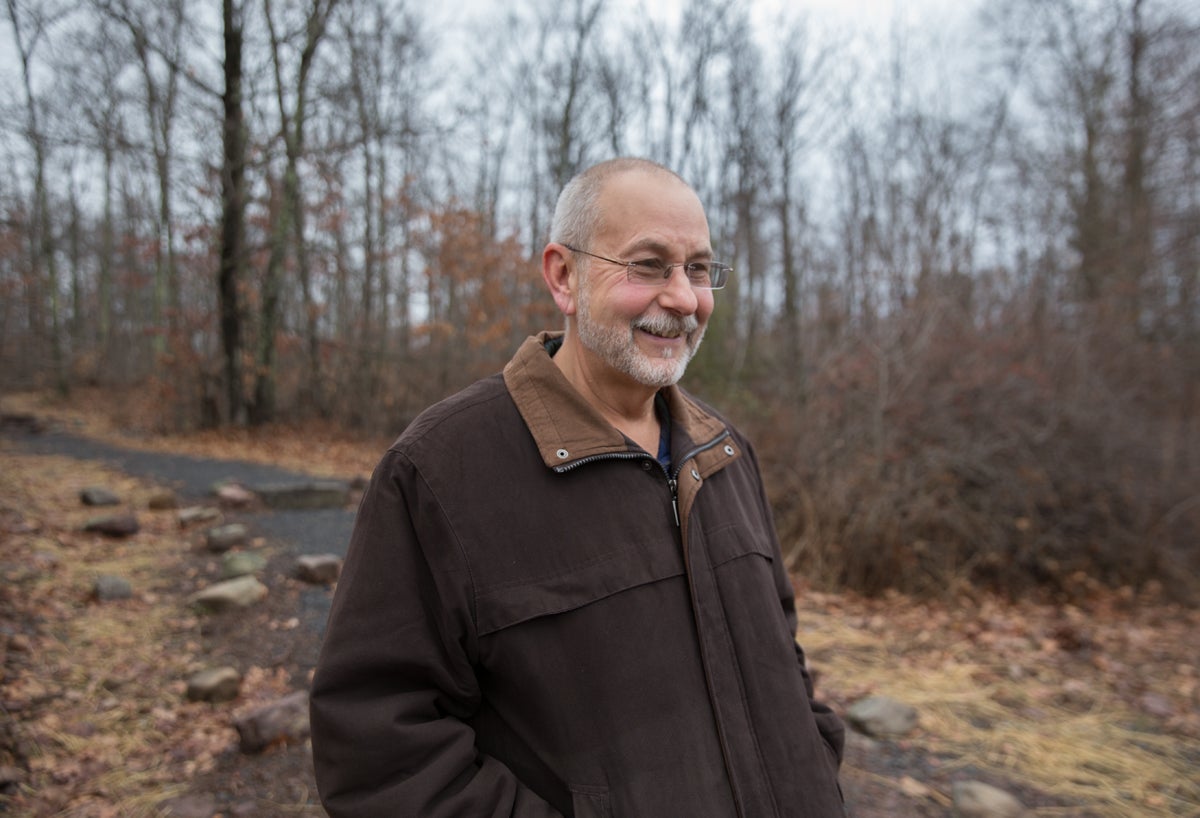

“Paradise Township is really like the name says, it’s paradise,” says Peter Gonze, a township supervisor.

Peter Gonze, one of Paradise Township’s supervisors, hikes up a trail built by the Mount Airy Casino Resort. (Lindsay Lazarski/WHYY)

Peter Gonze, one of Paradise Township’s supervisors, hikes up a trail built by the Mount Airy Casino Resort. (Lindsay Lazarski/WHYY)

Once flush with mountain resorts that have since shuttered or been in a slow decline, Gonze said the casino has been a boon for the community.

Paradise Township receives about $900,000 from the casino’s slot machine revenue and counts on Mount Airy for more than half of its yearly budget.

Gonze said the funds from the casino have mostly gone toward the town’s infrastructure, including maintaining 35 miles of winding mountainous roads and repairing bridges. The township also uses the money to help provide basic services such as the town’s library and community center, fire and ambulance, all while keeping tax rates low for the township’s roughly 3,000 residents.

Based on the Supreme Court ruling, Gonze expects Mount Airy will pay less in the future when it comes to the local share tax. He worries that would also mean less money for Paradise Township.

“It’s a two way street in that Mount Airy obviously brings in a tremendous amount of business and revenue for the township, but it comes at a cost.”

To Gonze and many other local leaders across the state, the casino money came as a promise from the state legislature to help pay for the wear and tear of hosting a casino.

“Most important to us is maintaining our fair share. That was the commitment of when Mount Airy came in,” said Gonze. “To change those rules at this point in time, I think it would be very unfair for the township as well as for the county.”

State Senator Mario Scavello (R – Monroe, Northampton County) represents Paradise Township and is chair of the senate’s Community, Economic and Recreational Development committee, which includes gaming.

Scavello said he doesn’t think the municipalities that host casinos, like Paradise Township, will be affected by changes to the law.

“Whatever the solution is going to be, the municipalities will get whatever dollars that was coming to them. You just don’t pull that out of an operating budget,” said Scavello.

But he said there could be an adjustment to the amount of local share dollars neighboring municipalities receive — especially in counties like Monroe and Erie — where the casinos are not making as much in slot revenues.

State Senator Mario Scavello is confident that the legislature will fix the law by the May deadline. (Lindsay Lazarski/WHYY)

State Senator Mario Scavello is confident that the legislature will fix the law by the May deadline. (Lindsay Lazarski/WHYY)

Keeping Promises

Erie County Executive Kathy Dahlkemper is also concerned. The county, which is home to the Presque Isle Downs & Casino, receives about 5.5 million from the casino. More than half of the money goes to pay down bond debt, while $1 million goes to improving their library system. Without the gaming funds, Dahlkemper said the county would have to ask for a tax increase to pay the debt.

“We agreed to have a casino. Not every county did. That was a deal we made a long time ago,” said Dahlkemper. “The state needs to keep its promise and keep it whole, so we don’t have to go after funding from our taxpayers when we were promised this casino money.”

To Dahlkemper, part of the issue in fixing the law, could also mean changing how funds are distributed. Typically, the community where the casino is located gets a share; as well as the county and some of the surrounding municipalities.

“What concerns me is that we’re opening up legislation, you know, we have to have new legislation,” Dahlkemper said. “People have seen the success of the casinos and what they have done for the counties and the communities that have casinos. I think people want a piece of that.”

Kathy Dahlkemper, Erie County executive, said she has been working closely with state lawmakers to ensure the county continues to receive local share tax funds. (Lindsay Lazarski/WHYY)

Kathy Dahlkemper, Erie County executive, said she has been working closely with state lawmakers to ensure the county continues to receive local share tax funds. (Lindsay Lazarski/WHYY)

In Dauphin County, home of the Hollywood Casino at Penn National Race Course, County Commissioner’s Chairman Jeff Haste said that it would be a game changer for the county and many of its municipalities if funds were to go away.

Most of the casino money goes to East Hanover where the casino is located and five surrounding communities; but the remaining dollars are pooled into a fund while a citizen’s committee reviews grant applications to distribute the rest of the funds.

Haste says that most, if not all, of the county’s 40 municipalities have gotten some funds from the casino.

One project that would not have happened without the local share money was a new state-of-the-art fire company. The fire company serves the county and is located near the Hollywood Casino, Interstate 81, Fort Indiantown Gap, and Hershey Park.

“If you think about it, that’s a lot of chicken barbecues,” said Haste. Typically, he said, central Pennsylvania fire companies have to fundraise to pay for new resources.

In addition to the fire company, funds from the casino have been used for infrastructure, public safety — including police and EMS services — and to help cover administrative costs in Dauphin County.

Haste said the local share tax is critical to hosting a casino.

“It’s sort of odd that a little over 10 years later, they are thinking about reneging on their contracts with local municipalities and that’s exactly what it would be,” said Haste. “If they take the funds that were committed to these local communities to buy off votes somewhere else, they have reneged on a commitment to this community.”

Dauphin County Commissioner’s Chairman Jeff Haste remembers when state lawmakers passed the gaming legislation and said there was a lot of fear among communities about hosting a casino. (Lindsay Lazarski/WHYY)

Dauphin County Commissioner’s Chairman Jeff Haste remembers when state lawmakers passed the gaming legislation and said there was a lot of fear among communities about hosting a casino. (Lindsay Lazarski/WHYY)

Striking a Deal

To ensure gaming funds would continue to reach its local communities, Dauphin County signed a memorandum of understanding last November with Hollywood Casino’s parent company Penn National Gaming, Inc. Penn National agreed to give the county $6.5 million through the end of June this year.

Eric Schippers, senior vice president of public affairs for Penn National Gaming, said giving money to the county shows their commitment to the community. If the legislature does not fix the law before July 1, Schippers said they would extend the agreement.

“For us, it was always our understanding that it was part of the rules of the game. We were going to be providing these payments to our host communities,” said Schippers. “And the reason we signed the memorandum of understanding is to provide some breathing room to keep those payments going while the legislature gets to a long-term fix.”

Other casinos followed suit, agreeing to continue to make payments to local communities including: Mohegan Sun Pocono, Parx Casino, Harrah’s Philadelphia Casino and Racetrack, Meadows Racetrack & Casino, and Rivers Casino.

Long-term Fix

Robert Ambrose, an instructor of gaming and hospitality at Drexel University, said the casino industry is often viewed as a cash cow. At the same time, he understands the concerns communities have when it comes to hosting a casino and the associated costs.

To fix the legislation, Ambrose said lawmakers should look at the bigger picture of the gaming industry in the state.

“It’s a matter of everyone in Harrisburg and beyond getting together and looking at the fair share. What is the fair share?” said Ambrose. “If we can make most communities happy and everyone sees something of the pie. You have to remember it’s not just about gambling. It’s about the entire hospitality infrastructure when you bring a casino into a region.”

Ambrose added the bigger picture must include the possibility of expanding gaming in Pennsylvania.

Professor Robert Ambrose runs a casino and hospitality gaming lab for students at Drexel University. (Lindsay Lazarski/WHYY)

Professor Robert Ambrose runs a casino and hospitality gaming lab for students at Drexel University. (Lindsay Lazarski/WHYY)

As far as possible solutions from state lawmakers, State Senator Scavello is confident there will be a fix to the local share tax by the end of May.

Instead of 2 percent of a casino’s gross terminal revenue on slots or $10 million, whichever is greater, Scavello thinks an increase to a 4 percent tax on a casino’s gross terminal revenue of slots — including Philadelphia’s SugarHouse Casino — would achieve roughly the same statewide annual local share tax of about $143 million.

Casinos earning more money on slots would pay a greater local share tax.

Democratic Senate leader Jay Costa (D- Allegheny) sees a different solution to fix the law. Rather than a percentage increase, Costa proposes that casinos — including the Philly casino — pay an annual slot machine license renewal fee of $10 million.

“I think we have to have uniformity among everyone in the mix. So I think we said $10 million for everybody. That’s what they need to pay,” said Costa. “It wouldn’t be a percentage, it would be a flat $10 million.”

But to Mount Airy, a flat $10 million rate for every casino would violate the court’s September ruling.

“Mount Airy believes that the only solution that will pass constitutional muster is if there is a percentage tax on gross revenue that’s applied to every single casino,” said Sklar.

The legislature has until Memorial Day to fix the law before the Supreme Court’s ruling goes into effect.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.