Climate Fixers: Slowing down fashion with a century-old tradition in Collegeville, Pa.

Industrial farms damage waterways and contribute to climate change. But at Pa.’s only certified organic sheep farm in Montco, the sheep do all the hard work.

This story is part of the WHYY News Climate Desk, bringing you news and solutions for our changing region.

From the Poconos to the Jersey Shore to the mouth of the Delaware Bay, what do you want to know about climate change? What would you like us to cover? Get in touch.

Sheep have kept us warm and dry for thousands of years. Well-made woolen clothes and blankets can last a lifetime, and even be passed down from one generation to the next. At the Willow Creek Farm Preserve in Montgomery County, head shepherdess Melissa Smith says that, in addition to providing high quality yarn and fabric, she sees the farm as a climate solution.

“The sheep weed for free, they fertilize for free,” said Smith. “So we don’t use big mowers and lots of fossil fuels with tractors at a scale that we would have to typically if we weren’t using sheep as a way to take care of our farm.”

Smith also grows certified organic hay and straw so their 220 Shetland sheep can eat in the wintertime. And because there’s little disturbance to the soil, it helps sequester carbon.

“Of our 135-acre property, 70 acres are being cared for specifically for sheep in a very low impact fashion,” Smith said.

That’s not the case with many industrial-sized sheep farms, which often pollute nearby waterways with manure and erode the soil through overgrazing. Regardless of the size of the sheep farm, the animals do emit methane as part of their digestion process, and while Smith has not conducted a life-cycle assessment of her farm, other studies do point to the potential of soil carbon sequestration and changing diets, as potential ways to balance or mitigate those emissions.

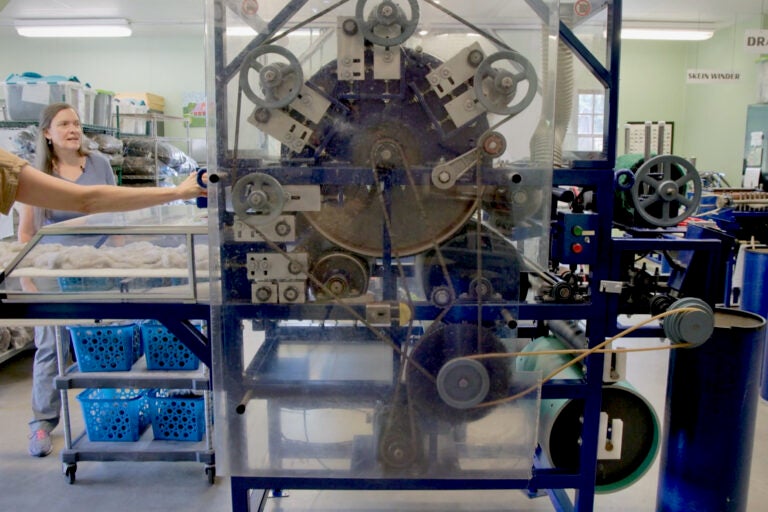

Another climate-friendly practice at Willow Creek is its on-site mill, so there’s no need to ship the wool off to a faraway processor. Smith said after the sheep are sheared, the Belfast Mini Mill makes it easy to go from “sheep to skein.”

The mechanized mill includes several pieces of equipment that take the raw wool, put it through a tumbler, a washer, a picker, a separator, a carder, a draw frame, a spinner, a plyer and, lastly, the skein winder, where the final ball of yarn is ready to be turned into a sweater, blanket or shawl.

Smith is part of a growing movement to “slow down” fashion by promoting the use of natural fibers. Current trends favor fast fashion, with its mixed synthetic fibers that are often made from fossil fuels. These clothes have become just too cheap, and for some who like the elasticity, too functional for many to resist buying. And because the quality is typically poor, or the fashion trends change so quickly, these garments will soon end up in a landfill or incinerator, contributing to pollution generally but also, increased carbon emissions.

“As consumers, we can make some choices with our clothing rather than buying things that may look great, but maybe we’re only gonna wear one or two times,” Smith said. “But investing in these slow pieces that can be timeless, but also something that you can have in your wardrobe for many years is something that you can do for yourself and to help climate change.”

Willow Creek’s woolens are woven into blankets by Bedfellow Blankets, and even used in sustainable furniture making by Common Object Studios as part of what’s known as a circular economy, which aims to create new products without creating additional waste.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.