Civic groups argue supervised injection site will boost crime

Neighborhood groups joined the FOP in supporting U.S. Attorney William McSwain’s effort to keep the nonprofit’s supervised injection site from opening.

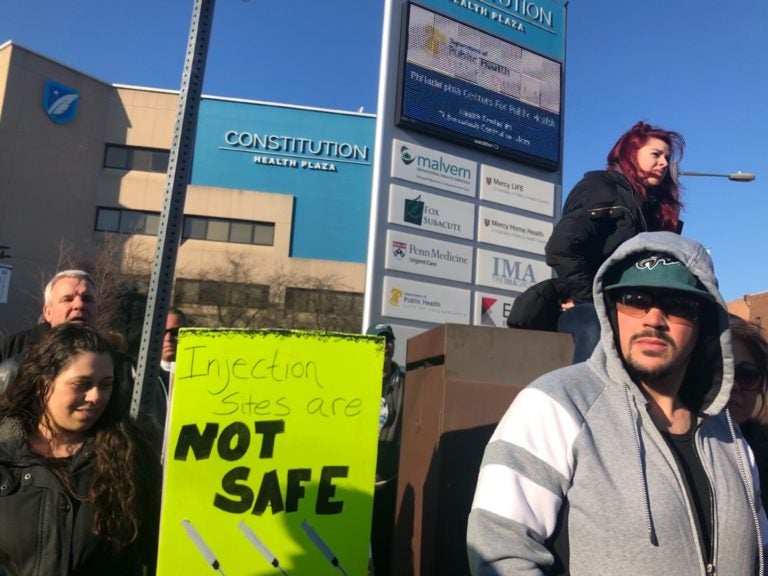

File photo: Hundreds gathered in South Philly to celebrate the temporary defeat of a supervised injection site in their neighborhood and protest putting one there in the future. (Nina Feldman/WHYY)

More than a dozen neighborhood associations from South Philadelphia and the River Wards have joined the Fraternal Order of Police in filing a court document in opposition to a planned supervised injection site. The filing, a “friend of the court” brief, supports U.S. Attorney William McSwain’s request for a stay that would prevent the site from opening while his appeal moves through the Third Circuit Court.

The amicus brief focuses on the impact such a site, where people could bring their own drugs to inject under medical supervision, would have on quality of life in the residential areas. The filing comes days after the nonprofit Safehouse announced it would open a supervised injection site in South Philly. The news was met with an upswell of opposition from nearby residents, causing Safehouse to retract its plans and its landlord to back out of the lease.

“The notion that drug addicts would visit the site like a family trip to the supermarket — there for a short time, and then back home — is fanciful,” wrote Michael McGinley, the lawyer representing the civic associations. “Instead, they would linger, and, when the injection site is closed, drug dealers would flood the area where Safehouse has been kind enough to concentrate their customers. This dynamic would cause precisely the predictable harms the law was intended to prevent.”

Donna Ciafre, a South Philly resident who opposes the site, said she is no stranger to the struggles of addiction. She said she asked her cousin, who uses heroin regularly and often stays on the street in South Philly, if she would use the site, and her cousin gave her a resounding yes.

“She’s going to come and cop from whoever she can, because I’m sure they’re going to be here selling whatever they can sell,” said Ciafre, referring to a common argument that drug dealers will flock to the neighborhood if they know they have a concentrated customer base there.

Ciafre said her cousin also referred to being near the site as a sort of “get out of jail free” card.

“If she gets stopped by a cop, she could easily say, `I’m going to the facility to use my drugs,’” Ciafre said.

Her conversation with her cousin echoed the amicus brief’s argument that if police don’t arrest people for possession or use nearby, a supervised injection site would create a “law free zone where dealers can, without fear of consequence, ply their trade.”

The city has said it would ensure there was no increase in illegal activity in the immediate vicinity.

Ciafre was one of hundreds who came together Sunday in front of the previously proposed location, Constitution Health Plaza on South Broad Street, to celebrate its temporary defeat. The gathering had been scheduled before the nonprofit changed its plans, but neighbors still came out to hail what they viewed as a victory resulting from the public outcry.

Though Safehouse would be the first supervised injection site in the United States, hundreds exist in Europe, Australia and Canada. The amicus brief criticized the impact on communities surrounding existing sites.

“Common sense, first-hand experience, and decades of research confirm that drug consumption sites would attract more addicts and additional drug dealers to service those users, lead to more crime, reduce public safety, and guarantee the degradation of the communities where they are located,” McGinley wrote.

The brief invokes reports from the supervised injection site in Calgary that opened in October 2017. According to police, the area has seen a 275% increase in drug-related calls to law enforcement since the site opened, and a 50% increase in violent crime. Police say that the rise is due to the site drawing drug dealers to the neighborhood, and that the increase has caused the Province of Alberta to dedicate an extra $200,000 to fighting crime and patrolling the neighborhood around the site.

Though the amicus brief endeavors to demonstrate that supervised injection sites draw crime and drugs to the neighborhoods where they open, the evidence it cites is, in fact, mixed in that regard. For instance, the brief cites one report in which the head of the police union in Melbourne, Australia, claims the injection site there caused a “one-stop shop” for crime. But it also cites a report in which a neighbor living directly adjacent to the Melbourne site defends it, and explains how public injection in the area had been much worse before it opened. That report, from The Guardian, also mentions that a nearby school endorsed the Melbourne site, as did the local business association.

The brief also cites quality-of-life concerns from residents in Toronto who live near the sites that range from property damage to public defecation.

According to further reporting from the Toronto Star, the year supervised injection sites started opening in the Moss Park area, crime actually decreased overall. Police statistics showed a slight increase in major theft, but a drop in assaults and robberies.

In general, academic research does not support the claim that supervised injection sites lead to an increase in neighborhood crime or drug-dealing.

A 2014 review of 75 studies on supervised injection sites, most of them in Vancouver and Sydney, found that the facilities did not increase drug trafficking or crime in the surrounding environments. Reports from the Vancouver Police Department, a year after the first supervised injection site in North America opened in the city’s Downtown Eastside neighborhood, found drug trafficking had not significantly increased or decreased in the surrounding area. In the review, the sites were found to be associated with reduced levels of public drug injections and dropped syringes.

Researchers acknowledge that the science is limited, in part because of the limitations of studying illicit activity among a vulnerable group.

Researchers have also expressed concerns about enrolling drug-using populations in what is considered the gold standard for research, a randomized controlled trial. Such a study gives one group access to an intervention and restricts access to a demographically identical group. Proponents of supervised injection sites believe so strongly in the lifesaving potential of supervised injection sites that they believe it would be unethical to knowingly deprive that option to a group.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.