City notified about potential closing of West Philly Mercy Hospital’s inpatient facility

Under a law enacted in reaction to Hahnemann University Hospital’s abrupt closure last summer, a hospital is required to give 180 days’ notice to the city.

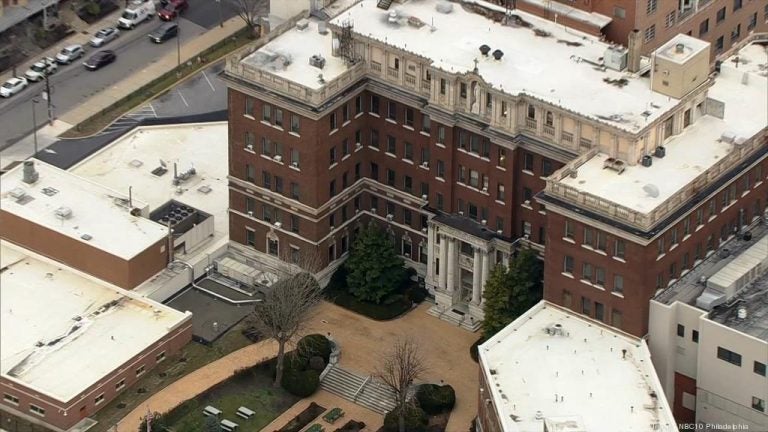

Mercy Philadelphia Hospital in West Philadelphia. (NBC10)

City health officials were notified Thursday about the possible end of acute inpatient services at Mercy Hospital in West Philadelphia.

The 157-bed facility has served the Cobbs Creek neighborhood for more than 100 years, providing emergency services, physical therapy, behavioral health care, and other services. Many of the hospital’s patients are on Medicaid or Medicare or are uninsured.

“Hospital officials assured City health officials that if these services are terminated, the process will take months and be conducted responsibly,” Philadelphia Health Commissioner Thomas Farley said in a statement. “The City will work with health system leaders on the future of this facility and on how to minimize adverse impacts on Philadelphians’ access to medical care.”

Under a new Philadelphia law enacted in direct reaction to Hahnemann University Hospital’s abrupt closure last summer, a hospital would be required to give 180 days’ notice to the city Department of Public Health before it closes, as opposed to the 90 days’ notice required under state law.

Although no timeline was shared with city officials about Mercy Philadelphia, the community teaching hospital could shutter by mid-August, nearly a year after Hahnemann closed its doors for good.

Trinity Health, one of the largest nonprofit Catholic health systems in the country, owns the West Philly hospital. Trinity also owns St. Mary’s Medical Center in Langhorne, Mercy Catholic Medical Center in Darby, Nazareth Hospital in Northeast Philadelphia, and St. Francis Healthcare in Wilmington.

Ann D’Antonio, vice president of marketing and communications for Trinity Health Mid-Atlantic, said in a statement that the health system has come to the “financial realization” that it cannot continue operating in an acute-care capacity long-term. It’s expected that Trinity will move much of Mercy Philadelphia’s inpatient care to the 188-bed Mercy Fitzgerald Hospital, about a 12-minute drive away.

Mercy Philadelphia, at 54th Street and Cedar Avenue, has long faced financial issues, underperforming in an area that is “over-bedded,” D’Antonio said. In 2018, the hospital saw 7,670 inpatient admissions. That same year, Philadelphia hospitals overall saw more than 300,000 inpatient admissions.

“In the coming months, we will begin the slow, deliberate and informed process of transforming our campus away from an inpatient hospital, shifting toward a model that can better and more sustainably serve the West Philadelphia community in the future,” D’Antonio said. “While we do not yet have all the answers, we promise to keep our patients, physicians and colleagues informed throughout every step of this process.”

The hospital employs roughly 900 people. One hundred medical residents — two of whom came to Mercy from Hahnemann — are currently split between Mercy Philadelphia and Mercy Fitzgerald hospitals. They attract 40 new medical residents each year.

D’Antonio said Trinity will be focused on providing opportunities to retain staff within Trinity Mid-Atlantic or elsewhere, though she added that it is too early to speculate on details.

Pennsylvania law does not allow for freestanding emergency rooms, so if inpatient services end, Mercy Philadelphia’s emergency room would have to close as well. In 2018, the hospital spent $15 million on expanding its emergency department, which reopened last fall. The ER had 48,000 visits in 2018.

If it closes, Mercy Philadelphia would be the third hospital in five years to do so, following Hahnemann last summer and St. Joseph’s Hospital in 2016.

City Councilmember Jamie Gauthier, whose district includes the hospital, addressed the potential closure during a council session on Thursday, saying it could have a “dramatic and detrimental impact on the ability of West and Southwest Philadelphians to access medical care in our city.”

“That means thousands of people will have to travel further away and wait longer for a doctor when they are experiencing an emergency,” Gauthier said. “…Black and brown communities are entitled to high-quality health care and to fair treatment by our health care system.”

Gauthier said that she heard from a Mercy Philadelphia employee Wednesday night who is worried about her future employment, with a child in school and bills to pay. She had heard of the possible closure through media reports.

Her office is watching the situation closely, Gauthier said, and she asked Mercy to be transparent about its plans.

Gauthier has a town hall scheduled for Wednesday, Feb. 19, with State Rep. Joanna McClinton regarding “unique issues facing residents of Cobbs Creek.”

WHYY’s Jake Blumgart contributed reporting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.