Celebrating a “rock star” of landscape architecture

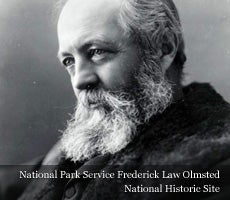

The cultural cognoscenti came out Thursday night in full force to honor Frederick Law Olmsted, a man whom Drew Becher, president of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, referred to as a “rock star” during his introductory remarks.

Culled from the Philadelphia parks, planning, and museum worlds, the assemblage gathered at the Philadelphia Museum of Art to view a screening of a new one-hour documentary, “The Olmsted Legacy.”

“I’m here because I’m an Olmsted dork!” laughed Tony Sorrentino, who holds a masters in city planning from Penn and now runs the university’s Office of the Executive Vice President.

The film’s writer and producer, Rebecca Messner, was on hand to talk about the celebrated landscape architect. “This film is just a tiny, tiny story of how parks have affected cities,” the young (she turns 25 next week) filmmaker told PlanPhilly in an interview before the event.

“As cities have deteriorated and been restored, parks have often been an agent of change.”

Indeed, that message is central to the film’s existence, which was spurred by — and funded by — Messner’s father, Mike. With his wife, Jenny, the former Wall Street investor runs a philanthropy, the Speedwell Foundation, and has lately spearheaded a public-private venture called Redfields to Greenfields. That effort is dedicated to converting “in the red” land such as dead malls and foreclosed homes into green spaces.

So far, the organization has examined the potential of such an idea in six cities, including Philadelphia. “When my dad was researching this idea, he became really inspired by Olmsted,” said Rebecca, who worked on her debut film with two experienced filmmakers, George deGolian and Michael White. “Olmsted’s form of planning is based on the idea that parks can generate benefits for decades to come,” she added.

The film was partly created, then, as a way to build a case. “We were surprised to learn that there wasn’t anything already out there,” Rebecca said. As such, the end of the movie lays it on a little thickly, with a barrage of sound bites about the physical and financial bonuses that parks offer.

Mostly, though, the documentary offers a dispassionate and fascinating look at what Olmsted himself referred to as a “decently restrained vagabond life.” His long and varied career included stints as a merchant seamen, journalist, sanitary commissioner, and goldmine superintendent.

Naturally, Olmsted’s pivotal role as designer of America’s first and still most-respected urban parks, which include New York’s Central Park and Prospect Park (both with Calvert Vaux), stands at the center of the film.

Other groundbreaking Olmsted creations in Boston and Buffalo get relatively short shrift, as do those he created in the Philadelphia area, Bryn Mawr’s campus and Brandywine Creek State Park. (Subsequent firms bearing his name were responsible for FDR Park, Marconi Plaza, Pastorius Park, and other portions of Fairmount Park — though not the core park.)

Messner said the film was shot in one week, which explains its geographic limitations, as well as the fact that Central Park is continually shown in the same “pastoral” (one style of landscape design) carpet of green. Would that the more “picturesque” (a second style) dramas of spring, winter, and autumn had been depicted.

In fact, the film’s general emphasis on the pastoral didn’t sit well with this viewer. For all of its talk of the democratizing value of parks, the documentary featured too much discussion centered on palliative benefits. I’d say the primary reason why Central Park is so successful is because it is packed with people and things to see and do, not because it provides an escape from its urban surroundings.

A minor point, though, and perhaps not central to the film’s mission.

Thoughtfully edited with a Ken Burns-type mix of still photographs, talking heads, and voiced-over readings of letters and journals, the film does pack a lot into its sixty minutes. A veritable who’s who in the field, from NYC parks commissioner, Adrian Benepe, to Olmsted biographer Witold Rybczynski, show up to offer their two cents.

And somehow Messner even convinced actor Kevin Kline to assume the role of Olmsted in voiceovers.

After the screening, about 75 of the 200 or so in attendance made their way into Stephen Starr’s re-made museum restaurant, Granite Hill, for a fundraising reception. Monies are slated to benefit ongoing improvements of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway and other PHS’ park efforts.

Contact the reporter at jgreco@planphilly.com

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.