Celebrating Henry Ossawa Tanner’s legacy of art, inspiration

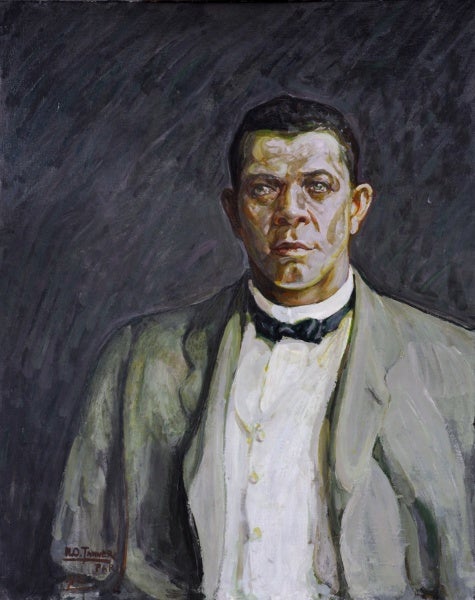

Henry Ossawa Tanner was a turn-of-last-century African-American artist who became one of the most important painters of his time.

His legacy, however, is complicated by race and religion. Two shows at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts work to put Tanner in context, then and now.

The larger, and more ambitious, show on the ground floor of PAFA’s modern Hamilton building is an overview of Tanner’s career. It opens with portraits of Tanner’s family and a peaked archway created by a scrim mimicking the architectural details of the old Frank Furness building next door. That is where Tanner began his formal art training in 1879, one of a very small group of African-American students.

“In the 19th century, people would not have referred to him as an African-American painter,” said curator Anna Marley. “The nicest thing they would have said was he was a black painter, and probably a lot worse.”

Thomas Eakins, an instructor at PAFA at the time, saw Tanner’s talent and took him under wing. After struggling to make a living as an artist (he briefly opened a photographer studio in Atlanta), Tanner did what every serious American painter did — he moved to Paris, like John Singer Sargent, like Cecilia Beaux, and like Eakins himself.

Aside from a few visits, Tanner never came back to the U.S.

“He went for all the reasons everybody else went,” said Tanner’s great-nephew, Lewis Tanner Moore. “He had added incentive to not be hindered by how he looked when he was there. He was able to compete and be judged based on the work.”

Modernizing religious art

Tanner, the son of a minister at the African Methodist Episcopalian Church in Philadelphia, remained devout all his life. It was his religious artwork that made his reputation internationally.

“He was the most talented religious painter of his generation, at a time religious painting was so popular. Every art museum needed one,” said Marley. “To be that leader is something we’ve lost in the 20th century, because of our tendency to see religious art as traditional, and dismiss it. Tanner made religious art modern. That is one of his great contributions.”

The exhibition moves from his early days at PAFA, to his large-scale religious work, to his travels in North Africa and the holy lands.

Upstairs, the exhibition “After Tanner” features work from the PAFA collection by African-American artists influenced by Tanner.

Tanner, who died in Paris in 1937, is regarded as a forerunner to the Harlem Renaissance. Years after his death, his reputation was burnished by the Civil Rights movement, when African-American artists of the 1960s and ’70s looked to Tanner as the father of African-American art.

He may not have entirely wanted that label.

“He was better received, was able to participate freely and feel his work was judged solely on the merit of the work in France,” said Moore, his great-nephew. “When he was here, it was a challenge to survive. He was able to make his mark on the world’s stage.”

Tanner wanted to be recognized as an artist of the highest order, regardless of his race. Marley says the few paintings featuring African-American subjects — most famously “The Banjo Lesson” — were not well received in the Paris salons.

Choosing to focus his talents on religious paintings made him one of the most sought-after artists of his day.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.