Ceasefire works to halt bloodshed in North Philly

Listen-

CeaseFire Philadelphia posts fliers at the site and memorial of a recent shooting in North Philadelphia. (Kimberly Paynter/For NewsWorks)

-

Denise Mickens's cousin was killed in a recent shooting on the block. She supports the efforts of CeaseFire Philly. (Kimberly Paynter/For NewsWorks)

-

CeaseFire Philadelphia outreach coordinator Quinzel Tomoney canvases the site of a recent shooting. (Kimberly Paynter/For NewsWorks)

-

CeaseFire Philadelphia volunteer Anton McCullough posts fliers onto abandon buildings in North Philadelphia. (Kimberly Paynter/For NewsWorks)

-

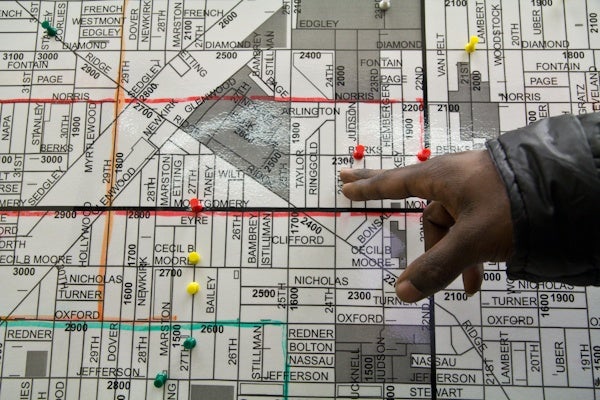

CeaseFire volunteer Anton McCullough shows what's known as a

-

CeaseFire Philadelphia outreach volunteers leave pamphlets in every available place. (Kimberly Paynter/For NewsWorks)

-

Outreach workers for CeaseFire Philadelphia hand out pamphlets and hang up fliers. (Kimberly Paynter/For NewsWorks)

In 2010, 10 percent of Philadelphia’s homicides were in the 22nd Police District, an area that is home to less than 2 percent of the city’s population.

When there’s a shooting in the North Philadelphia neighborhood, members of the group Ceasefire spring into action trying to prevent additional violence. But there’s a problem — the nascent program is running out of money.

Groups of kids just out of school head down the street joking and teasing each other. They pass stretches of North Philly row houses — some boarded up, others lovingly tended — as well as Ceasefire’s outreach coordinator Quinzel Tomoney as he hangs posters a few feet from a memorial with balloons and a teddy bear.

“This is the block where the victim got shot up at and he passed away, unfortunately. The shooting happened on the second of February,” said Tomoney. “This is called canvassing the neighborhood. Just so the community can see that this is unacceptable — what’s going on — in the city of Philadelphia and we need everybody involved to slow it down.”

This community may have a lot of violence, but it’s not numb to death.

Denise Mickens, sitting a few houses down from the memorial to her cousin, watched Tomoney and others tape up anti-violence posters.

Mickens, who was born and raised in the neighborhood, says her cousin was a good person.

“It was wrong how they did him,” she said. “He took care of his kids. His mom, that was her only child. It’s sad. I don’t know what it’s going to take around here for them to stop it. It don’t make no sense. It really don’t.”

Mickens says she’s happy to see the outreach workers.

Sending the right messenger

The Ceasefire program operates on the belief that to stop the violence, it’s vital to send not just the right message, but the right messenger.

Tomoney started selling drugs when he was 14 to help his mom pay the bills. Now he uses that experience, and the six years he served in prison, to talk to young people about how he can help them get off the corners and find a legitimate job or re-enroll in school.

Outreach worker Terry Starks, too, knows where these kids have been.

“In 2002, I was shot five times in the chest. I was unconscious for 19 days and when I woke up, I knew I had a calling. I was out in the streets selling drugs and stuff like that,” Starks said. “For me, canvassing these areas, trying to fix the problem, and being able to go to the hospital and talk to ’em, it’s emotional for me.”

Ceasefire has 51 clients, said executive director Marla Davis Bellamy. Outreach workers are required to visit them at least six times a month and call them at least twice a week to encourage them to turn their lives around.

Davis Bellamy, also the co-director for the Center for Bioethics, Urban Health, and Policy at the Temple School of Medicine, said outreach workers hit the streets after each shooting or homicide. The “shooting response” is like a prayer vigil or a march to rally the community.

She says there are early signs of progress.

“The 22nd has the highest number of homicides and shootings in the city,” she said. “Given the fact that there were 34 homicides in the city in terms of January and only one of them coming from the District, I think is promising.”

But with funding tight, right now, Ceasefire is just trying to get through the next few months.

Davis Bellamy says the program is operating on a $250,000 grant from the Pennsylvania Commission on Crime and Delinquency and looking to private and public sources for more money.

“The hope, and certainly the prayer, is that we’ll be able to identify some additional dollars. From community foundations, we’ve had some preliminary discussions with the city, we’ve shared some of our successes and challenges with the police department,” she said. “I think that with the support of Mayor Nutter and others that well be able to secure the funding that we need to continue beyond June 30.”

Sticking together, saving kids

There is a lot of work to be done, says Ceasefire volunteer Anton McCullough. His eyes are hidden by big sunglasses but his emotions come out in his voice.

“It’s sad the way young black males and kids glorify killing each other up over nothing,” he said.

McCullough, released from prison in 2010 after serving 12 years for attempted murder, says now he’s used to giving advice like a big brother.

“When I be walking around asking kids, ‘What are you doing?’ They’re like, ‘I’m selling drugs.’

“Well how much you make? ‘Well I make $200.’ I say, ‘You comfortable with that?’ And then that’s when Terry will step in or Quinzel and they be like, ‘Here man, take my card and we gonna try to get you a job,'” McCullough says.

McCullough says he’s convinced this program will work, it’s just going to take time.

“If people stick together, like the team we got now, we all know each other so we gonna stick together and we gonna try to save our community and we gonna try to save these kids,” he says.

By June, once outreach workers will have been on the streets for a year, Davis Bellamy hopes to see at least a 10 percent reduction in homicides and shootings in the area.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.