Capitol recap: How does state aid for local pensions work, exactly?

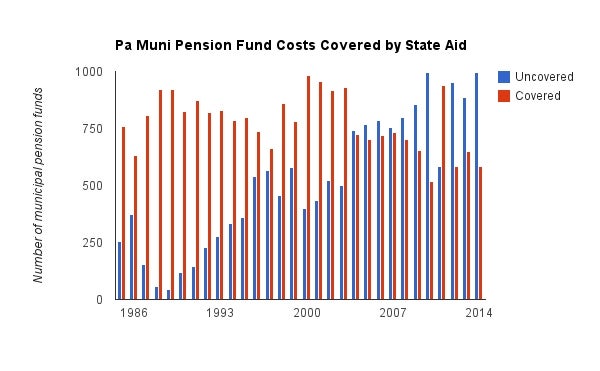

Annual costs for municipal pensions in Pennsylvania are growing faster than available state aid. (Data source: Pennsylvania Employee Retirement Commission)

Pennsylvania is rare among the states for giving aid to municipal pensions, allocating nearly $250 million last year to 1,500 municipalities.

Many of those funds are distressed, which means they’re projected to run out of money to cover retirement benefits promised to retirees and current workers, once retired.

But distress doesn’t factor into how much state aid is received.

State Auditor General Eugene DePasquale says that needs to change.

As employers, municipalities have to contribute to their pension funds every year, and some get enough state aid to fully cover what they owe.

State aid covers much less in other municipalities, though, even those with distressed pension funds such as York, Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. Aid to those cities amounts to less than 20 percent of annual pension costs, DePasquale says.”To me, that’s insane. There needs to be some level of fairness,” he says.

Currently, aid amounts are based on workforce size, pension costs and how much the state takes in as foreign insurance tax revenue in a given year. Last year, for example, the state collected nearly $250 million in foreign fire and casulaty insurance company taxes.

Municipalities report their pension costs and workforce size to the Pennsylvania Employee Retirement Commission, or PERC. PERC figures out its award cap—known as “unit value”—by dividing the available insurance tax proceeds by the statewide total of all municipalities’ worker units (the system counts non-uniform employees as a single unit and uniform—aka, public safety—employees as two units).

Last year, the unit value was $3,873.

Municipalities also have reported their actual pension costs per worker unit, and receive an allocation based on whichever figure is lower.

So Township A with 10 worker units and a $3,000 per worker unit pension costs would get $30,000.

And City B with 20 worker units and a $4,000 per work unit pension cost would get $77,460, leaving the city—as employer—to pay $2,540.

Pension costs are growing faster than foreign insurance revenue, though, so more and more municipalities are in the same boat as City B. Fewer get their costs fully covered, as in Township A.

About 38 percent of municipalities receiving state aid get enough to fully cover their pension costs, according to PERC’s latest report.

Which municipalities? Hard to say.

Municipalities have to specify the amount of state aid received and money they, as employers, pay into the fund in reports to to the PERC biannually.

But they often don’t report that accurately, according to the commission’s deputy director for programs and technology, Bernard Kozlowski. Kozlowski cautions against considering distress when awarding aid.

“Then what will keep (municipalities) from raising the pensions to get more money?” Kozlowski says.

National pensions experts echo his thoughts.

DePasquale agrees that awards based solely on distress would encourage “bad behavior,” as far as fund management goes.

But DePasquale says adjusting the formula to account somehow for distress might be preferable to wide-scale borrowing by distressed funds. He’s also advocating for changing retirement plan structures to reduce costs to local government, and tying state aid to adhering to the rules (which is in place now, albeit very rarely used).

But that likely would affect future hires and not current retirees and workers.

In the meantime, municipalities are going to need to come up with money somehow to deal with pension funding shortfalls, DePasquale says.

Kozlowski says this isn’t the way to go. Cutting aid awards back by, say, 25 percent for all but the severely distressed pension funds wouldn’t help much, he says.”It’s a little more money in the pot, but nowhere near enough to help distressed places,” Kozlowski says.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.